Humans often pride themselves on being the only mammals on Earth who can cultivate crops. Since the advent of primitive agriculture around 10,000 years ago, our ancestors have solved the problem of hunger.

The abundant food supply since then has allowed humanity to increase its population and enhance nutrition, contributing to growth in both height and weight. It is undeniable that agriculture has played a significant role in the development and prosperity of human civilization.

This is why, in simulation games depicting the development of civilizations, such as Age of Empires, the activities of farming and agriculture in the later stages are emphasized over hunting and gathering.

But now, there is a first non-human mammal that seems to know how to do this as well. In a recent study published in Current Biology, scientists suggest that the Gopher, or pocket gopher, may also engage in agricultural practices.

These pocket gophers prefer to eat the roots of longleaf pines. Consequently, they often dig burrows beneath fields or forests where these trees grow. However, Gophers do not just harvest roots that grow into their burrows; they also cultivate new roots for food.

These rodents create dedicated farming areas within their burrow systems, often extending hundreds of meters with winding tunnels. They also store urine and feces to fertilize the roots, thereby increasing yield.

While there is some scientific debate about the definition of agriculture and whether the behavior of pocket gophers constitutes true farming, the authors of the new study point to clear signs that these animals have managed a form of agriculture, at least comparable to how humans manage forests.

Biologist Francis Putz from the University of Florida stated: “The pocket gophers in this Southeast region are the first non-human mammals known to engage in agriculture. Previously, agricultural practices were only observed in ants, beetles, and termites, not in other mammals (aside from humans).”

You might not know that many animal species also engage in farming

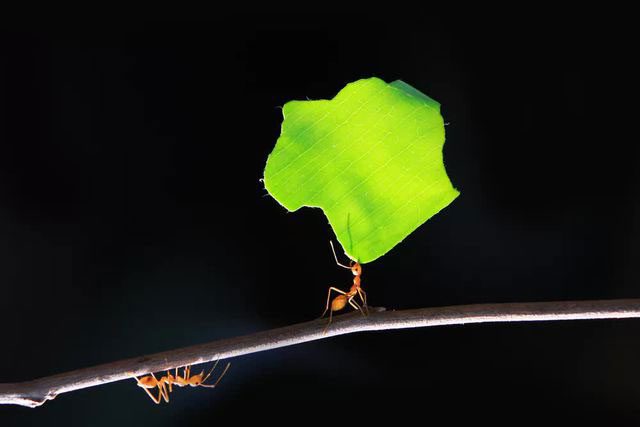

This is true for some insect species, such as ants. Leafcutter ants (Atta, Acromyrmex) in Central and South America are known for their ability to cultivate fungus. Many people mistakenly believe that these ants cut leaves to eat. However, the leaves are merely a food source for their cultivated fungus.

In the forests of Mexico, you can easily spot these ants carrying leaves, grass, and sometimes even flowers that are twenty times larger than their bodies back to their nests. The purpose is to feed the fungi they cultivate.

They only eat the fungi after it has grown because it is more nutritious than the leaves. Although this is a clever strategy, these ants occasionally face crop failures. If their fungus farming encounters difficulties, leafcutter ants may face starvation in their nests.

Many people think leafcutter ants eat leaves, but they only bring leaves back to cultivate fungus.

Another ant species, known as the black garden ant (Lasius niger), employs a different farming strategy. This species tends to aphids within a designed habitat, much like how humans raise dairy cows. The goal is to “milk” the aphids for their sugary secretions, which serve as a rich food source for the ants.

Black garden ants actually herd aphids. They often create areas rich in nutrients for the aphids to reside while guarding them from predators.

During the cold winter nights, ants carry the aphids into their nests to keep them warm, then herd them outside during the day. To prevent the aphids from flying away as they grow in the pastures, some ants even clip their wings.

Black garden ants also keep aphid eggs so that when they move to a new territory, these eggs can hatch into new aphids to be farmed there. The most fascinating part is that ants can train aphids to be milked.

Well-trained aphids will fill up with honeydew until the ants stroke them with their antennae, prompting the aphids to release their secretions. With such skilled techniques, ants may indeed be the first civilization on Earth to practice farming, rather than humans.

Black garden ants and a farm where they tend aphids.

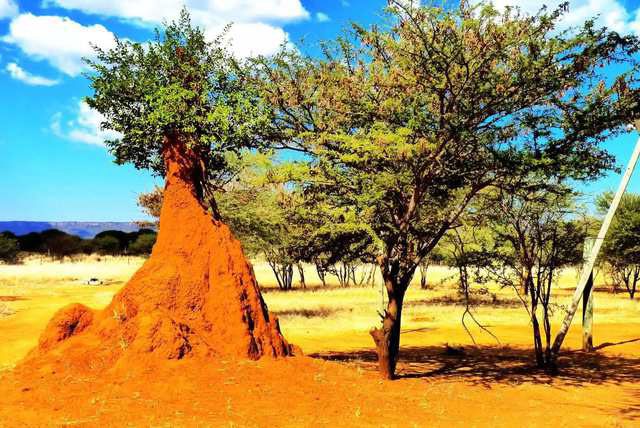

Returning to agriculture based on cultivation, we also have termites that know how to grow fungus. Termite mounds are often designed with complex structures, including chambers that maintain appropriate temperature and humidity for fungus growth. Like leafcutter ants, termites cultivate fungus in these chambers to obtain food. They collect leaves and wood to chew for the fungus to thrive.

The Ambrosia beetle also cultivates fungus in a similar manner. They manage their crops within decaying tree bark. Many people mistakenly believe that this species bores into trees and eats wood. However, the sawdust they excavate from the wood is only for nurturing fungus. Both adult and juvenile Ambrosia beetles feed on the fungus.

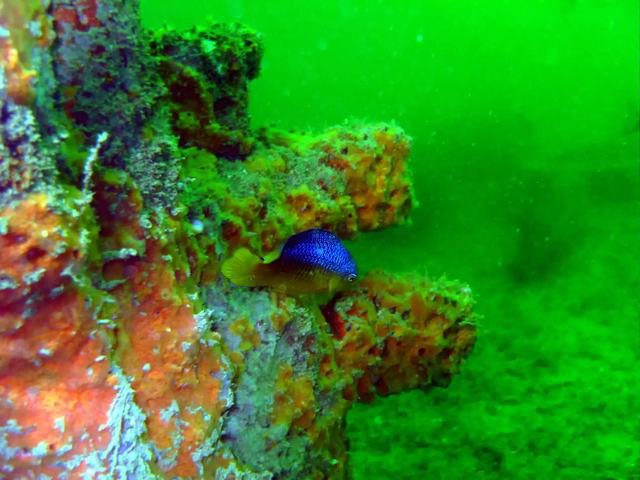

Another fungus-cultivating species is the Marsh Periwinkle (Littoraria irrorata). They are known for their ability to cultivate parasitic fungi on grass leaves. These snails use their rough tongues to carve deep grooves in the leaves, much like a plow. Subsequently, fungi can grow within these grooves. Daily, these snails defecate in the grooves to fertilize their crops.

Underwater, you can expect to find agriculture from fish. The dame fish are believed to cultivate algae. They care for their algae fields and fiercely protect their territory. These fish often attack any creatures that swim too close to their crops.

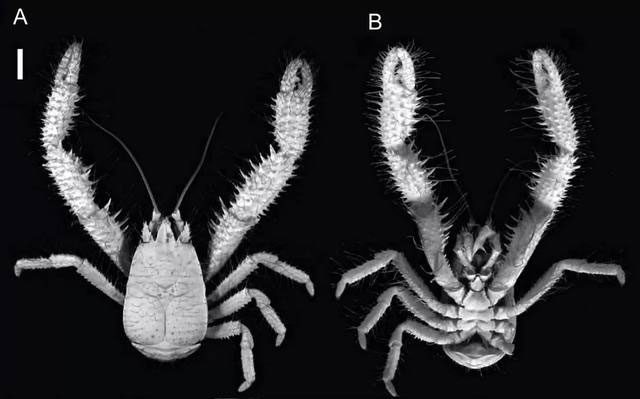

Finally, there is a species of crab known as Yeti. These crabs cultivate bacteria on their hairy claws. The crabs feed the bacteria methane from vents on the ocean floor. In return, the bacteria convert inorganic substances into oxygen and sulfides that the crabs need to grow. When the crabs are ready to harvest their crops, they use their comb-like teeth to gather their meals from the hairs on their claws.

Now, scientists have discovered the first mammal known to cultivate crops

It can be seen that while agriculture is not an inaccessible aspect for many insect and mollusk species, as well as crustaceans, it is a relatively new concept for mammals, apart from humans.

Even large intelligent species that are closely related to us remain in a foraging society. Yet, there is now a species of pocket gopher that seems to understand farming.

These Gophers (Geomys pinetis) are small marsupial rodents found in North and Central America. They weigh around 200 grams, are 15-20 cm long, and have brown-gray fur. Their most formidable tools are their large teeth and claws, which help them dig burrows beneath fields to eat roots.

Gopher spends almost its entire life underground.

Gophers spend nearly their entire lives underground, digging extensive tunnels that can be as long as a football field. Occasionally, these pocket gophers emerge from the ground during mating season.

To study the behavior of this rodent, biologist Francis Putz at the University of Florida visited the Flamingo Hammock, a rural land that Putz partly owns and operates for research.

He, along with his university students, used a borescope (often used to inspect plumbing and automotive engines) to look inside the gopher burrows. Observing the social life of these creatures, Putz found that the gophers not only know how to eat roots but also engage in farming.

Gopher mice not only eat plant roots, but they also engage in agriculture.

Specifically, Gopher mice typically harvest the roots of longleaf pine or certain herbaceous plants that grow within their tunnels. After harvesting, they will urinate and defecate throughout the tunnels as a form of fertilization for the roots to grow longer.

This waste creates a dense environment rich in moisture and nutrients that stimulates the roots to continue developing. Through this fertilization process, these American pouch mice can grow enough roots to meet 20-60% of their daily caloric needs, only needing to forage for new roots to supplement the rest.

While this may not be a complex form of agriculture, researchers believe that Gopher mice display behaviors similar to how humans manage natural forest areas, including the sustainable harvesting of crops and taking care of a portion of it for future regrowth.

A Gopher mouse pulling roots down for harvesting

Putz notes that in most cases, American pouch mice do not pull entire plants into their tunnels and consume everything. They always leave some plants behind to nourish their roots and allow them to grow longer.

This activity requires both time and energy costs. These mice also know how to protect their crops.

“They are trying to create the perfect environment for root growth and fertilizing their crops“, says zoologist Veronica Selden from the University of Florida. “All of these conditions qualify as a low-level food production system.“

The new study was published in the journal Current Biology.