Did you know that if you let a knight piece continuously jump on an 8×8 chessboard, its seemingly zigzag moves can fill all 64 squares of the board? This means a knight can reach any position it desires, given enough time.

Do you remember the maze puzzles we used to play as children? Those winding zigzag paths printed on rulers, notebooks, or certain issues of the Hoa Học Trò magazine. We often traced our pencils on them to find a way out for a marble or an imaginary mouse.

Now, a group of scientists from the University of Bristol in the UK has created something they call the world’s hardest maze. It will challenge your brain as this maze can nearly expand to infinite sizes.

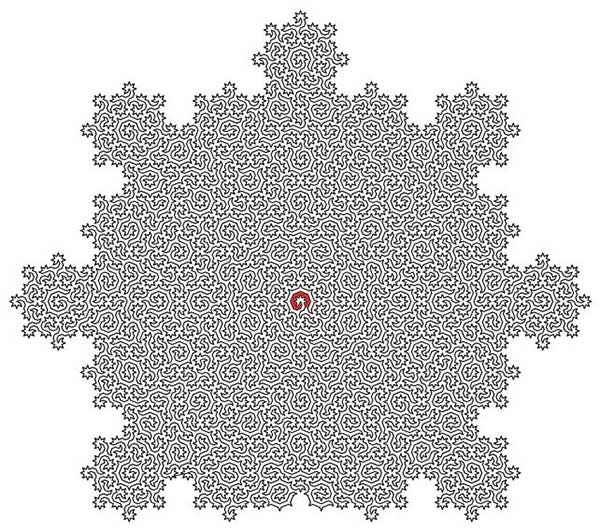

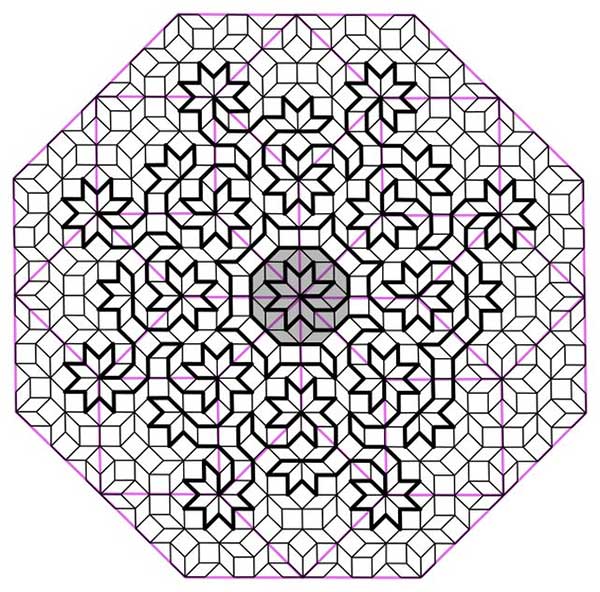

Even a scaled-down version of it will make you use your pencil. If you don’t believe it, try to find a way out for the imaginary marble in this maze, assuming it is trapped in the red area:

This maze was created by Dr. Felix Flicker, a physicist at the University of Bristol, using theories of Hamiltonian cycles, Ammann-Beenker tiling, and fractal models. Notably, it was inspired by the knight’s moves on a chessboard.

“When we created this maze and looked at the shapes of its lines, we noticed they formed incredibly complex pathways. The size of the mazes increases exponentially—and it seems there are countless such mazes,” Flicker explained.

The Knight and Hamiltonian Cycles

Anyone who has played chess knows that the knight is one of the most challenging pieces on the board. First, it jumps two squares forward, then one square to the side.

However, did you know that if you let a knight continuously jump on an 8×8 chessboard, these zigzag moves can fill all 64 squares? This means a knight can reach any position it desires, given enough time.

“This is an example of a Hamiltonian cycle, a loop that passes through every point on a map, stopping at each point only once,” Dr. Flicker said.

The knight’s path on the chessboard will fill it completely and form a Hamiltonian cycle.

You can see many more examples of Hamiltonian cycles in nature, such as quasicrystals, a type of solid that is a hybrid between ordered crystals and amorphous solids.

In an ordered crystal—like salt, diamond, or quartz—all their atoms are arranged in a very neat, repeating pattern in three-dimensional space.

You can take a part of this lattice and stack it on another part, and they will fit perfectly.

Amorphous solids are different. They are solids where the atoms are simply arranged chaotically. Glass, asphalt, and pitch are examples of amorphous solids.

Situated between these two types is the quasicrystal, a material whose atoms are arranged almost orderly, as if forming a crystalline pattern. However, if you zoom into the patterns of a quasicrystal, you’ll find they are not identical and cannot be perfectly stacked on each other.

Helping Scientists Create the World’s Hardest Maze

While contemplating quasicrystals, Dr. Flicker noticed their patterns closely resemble a mathematical concept known as aperiodic tiling, which consists of non-repeating shape patterns:

An example of aperiodic tiling.

Using the theory of aperiodic tiling as a foundation, Dr. Flicker created Hamiltonian cycles that he believes describe a quasicrystal that could exist in real life.

The cycles created only visit each atom in the quasicrystal once, connecting all atoms in a single, non-intersecting line, and linking from start to finish.

If the quasicrystal patterns are placed next to each other, they can extend infinitely, creating a type of mathematical model called a fractal, where the smallest patterns, when zoomed in, resemble the larger pattern.

This self-similarity means that natural fractals create an extremely challenging maze to solve.

An example of a fractal.

More than Just a Game

Of course, the scientists’ research into a complex maze isn’t just to challenge each other during their free time in the lab.

Dr. Flicker stated that discovering a new Hamiltonian cycle is already a significant milestone in mathematics. These Hamiltonian cycles can be applied to optimal routing algorithms on Google Maps, folding proteins to create drugs, and solving many other complex problems.

Interestingly, Hamiltonian cycles also hold significant importance for carbon capture. In industrial activities, engineers today use adsorption mechanisms to extract molecules from liquids by binding them to crystals.

If we can use quasicrystals for this process, they may have the capability to absorb more molecules and pack them tightly along the maze pathways in the Hamiltonian cycle.

Dr. Felix Flicker, the maze’s creator, is a physicist from the University of Bristol.

“Our research shows that quasicrystals can be better than crystals in certain adsorption applications,” Dr. Flicker noted.

“For example, curved shape molecules will find more ways to fall into the unevenly arranged atoms of a quasicrystal. Quasicrystals are also quite brittle, meaning they can easily break into smaller particles. This maximizes their surface area in adsorption applications.”

Of course, that’s a matter for engineers and scientists. For us, we just need to know that they have created the most challenging, infinite maze in the world.

So, in the upcoming board game session at the office, if you want to challenge someone who claims they can solve any maze game, give them this infinite model. They might just spend a lifetime trying to escape that maze.

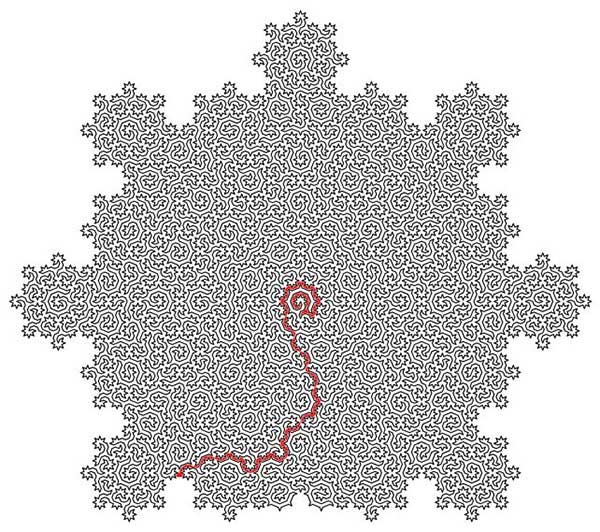

Below is the solution to the maze at the beginning of this article: