“Twist it, lick it, dunk it” is one of the most familiar slogans for many consumers and has become a natural habit when enjoying Oreo cookies.

Dr. Crystal Owen and her colleagues published their research findings in the journal Physics of Fluids. (Image: Wall Street Journal).

However, a question has lingered for a century, which even the creator of this advertising message could not answer: how to twist the cookie while ensuring an even layer of cream in the middle, rather than just sticking to one side of the cookie as is usual.

Michelle Deignan, Vice President of Oreo in the U.S., once shared that there is no secret to the twisting technique. Therefore, a group of scientists at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) researched this unanswered question.

“It’s frustrating that every time you twist a cookie, the cream from one half sticks to the other half,” Crystal Owens, a mechanical engineering PhD at MIT, shared.

For Crystal Owens, who holds a PhD in mechanical engineering from MIT, pursuing equal cream distribution in Oreo cookies—which easily separates with one side having almost no cream—has been a lifelong dream.

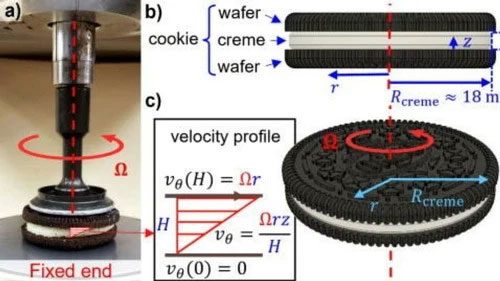

Recently, she finally had the opportunity to lead researchers in conducting probabilistic tests to achieve this sacred result by using a rheometer, a tool for measuring the torque and flow of various substances.

The experiments showed that even in laboratory conditions, it is impossible to separate two Oreo cookie halves with an equal amount of cream on both sides, regardless of how large the operation is. The research report was published in the journal Physics of Fluids, introducing the new term “Oreology”, defined as “the study of the flow and breakage of sandwich cookies.”

“Personally, I was driven by the desire to solve a challenge that puzzled me as a child: how to open an Oreo cookie with an even cream distribution on both sides?” Dr. Owens said in an email. “I love the taste of cookies with cream exposed. If I bite into a cookie without cream, it’s too dry for me, and if I dip it into milk, the cookie breaks too quickly.”

“When I came to MIT, I learned how to use the rheometer in the lab, witnessing it twist a liquid sample between parallel plates to measure flow,” she continued. “Initially, I used my rheometer to test inks based on the carbon nanotubes I was designing to 3D print flexible electronic devices. But one day, I realized I had enough tools and knowledge to tackle the challenge with Oreo cookies.”

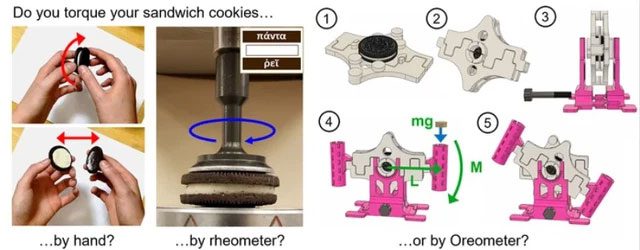

A 3D printing device created to study how to open Oreo cookies.

Owens and her colleagues took a methodical approach to find answers to this important question. They even invented the “Oreometer”, a 3D printing device specifically designed for Oreo cookies and similarly sized round objects.

After separating the Oreos with tools, the research team visually examined the cream ratio on each cookie and recorded their findings. Several variations in the experiments were also introduced, such as dipping the cookies in milk, changing the rotation speed of the rheometer, and testing different Oreo flavors. However, despite their best efforts, the researchers could not find a solution to the problem that had puzzled Dr. Owens for decades.

“The results confirmed what I observed as a child—we didn’t find any tips for opening Oreo cookies,” Owens stated. “Essentially, in all possible twisting methods, the cream tends to separate from one cookie half, leaving one half almost bare and the other half with almost all the cream. In cases where cream remains on both cookie halves, it tends to split evenly resulting in each half having a ‘half-moon’ rather than a thin layer. Therefore, there’s no trick to achieving evenly distributed cream just by twisting. You’ll have to mix it back manually if you want uniformity.”

“This surprised me because I imagined that if you twist an Oreo perfectly, you would achieve perfect cream distribution. But clearly, that is not how physics works,” she continued.

Dr. Owens was also surprised to learn that Oreo cookies are not filled with cream, but with crème. It’s more like a cream coating rather than a frosting like cream cheese or filling in pastries, and it actually does not contain milk. “However, the rheological properties remain similar across different liquids,” she added.

While the research team has now confirmed the elusive properties of Oreo cookies, the new study is filled with new revelations about this popular snack and its intriguing characteristics. Owens and her colleagues first reported that Oreo cookies fall into the so-called “gummy” texture mode.

The research team attached cookies to the rheometer to study the effects of rotation speed, flavor, and cream amount on Oreo samples.

According to the study, the scientists also calculated the “decline in the strength of the chocolate wafer over time after being soaked in milk,” concluding that Oreo cookies “lose significant structure” within a minute of exposure to milk. These findings pose another set of challenges to Owens’ worldview regarding Oreo cookies.

“I used to think you needed to crush the cookie and let it soak in milk to create the best flavor, but this type of cookie would break down too quickly,” she said. “I thought that a cookie becoming soft meant it had enough milk, but it turns out the cookie can still feel ‘dry’ and need more milk because it requires time to dissolve after being wet. According to another study I found, cookies absorb the most milk just 5 seconds after soaking, so there’s a ‘sweet spot’ in timing before they spoil.”

Owens hopes her work will make people think about the scientific concepts underpinning their snacks and everyday indulgences.

“There are many questions we couldn’t fully answer in our first study, so we welcome others to contribute their ideas and experiments,” she concluded. “We are considering a follow-up study on crème. For now, we will just keep Oreo cookies in the break room to ‘test flavors’ between other experiments, and maybe we’ll find a new puzzle to solve.”

The Oreo study is intended for entertainment purposes

Thomas Schlathölter, a physicist at the University of Groningen, also organized a group of students to replicate the MIT experiment with Oreos sold in the Netherlands. They tried twisting the cookies by hand, and the results were quite surprising, as many students were able to separate the cookies fairly evenly. “Oreo cookies sold in the European market seem different,” Thomas Schlathölter remarked.

According to the physicist, the difference lies in the structure of the cream. Dr. Owen also agreed with this view, suggesting that the manufacturing process of cookies in Europe differs from that in other parts of the world.

According to the Wall Street Journal, Oreo cookies are sold in over 100 different countries, and many people guide others on how to eat them correctly.

There are many instructional videos on YouTube about the right way to eat Oreos. (Image: Steve’s Real World).

On YouTube, a video with over 13 million views titled “You’ve Been Eating Oreos WRONG.” In the video, a woman uses a fork to retrieve a cookie and dips it into milk. Many other videos also contain similar content about Oreos, using straws to soak the cream inside in milk.

Dr. Crystal Owens stated that she would apply the research model to snacks with similar structures such as macarons, cream-filled cookies, and peanut butter cookies.

The Oreo cookie research is indeed fascinating and helps make her dry academic activities more known to the public. “The research topic came to me from a personal curiosity, but I guess everyone will respond positively,” Owens shared.