So far, axions remain a concept on paper.

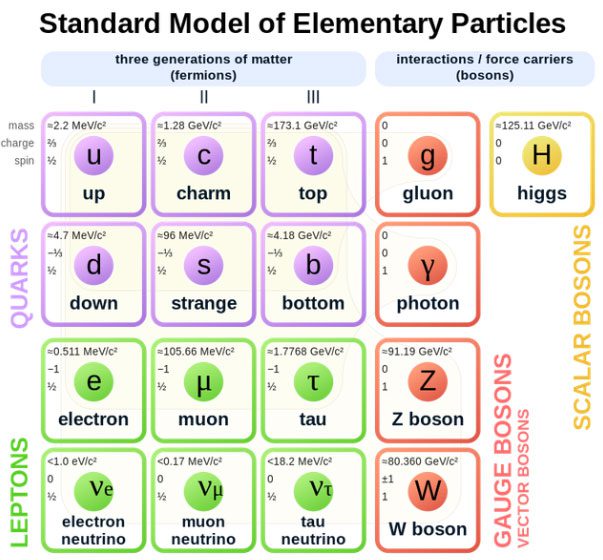

The fundamental particles in the Standard Model of particle physics, which describes three of the four fundamental forces we know, are still incomplete.

This model classifies all subatomic particles, also known as fundamental particles. The particles in this model are divided into fundamental fermions, which include six types of quarks and six types of leptons (with the electron being one of them); and fundamental bosons, which include the Higgs boson (often referred to as the “God Particle”), photons representing electromagnetic force, gluons representing strong force, and W and Z bosons representing weak force.

Standard Model of Fundamental Particles – (Image: Wikimedia Commons).

Theoretically, there is at least one more undiscovered particle; scientists refer to it as the “axion”. If the existence of axions in the universe can be proven, science will successfully solve many challenging problems that have puzzled researchers, and even name one of the types of dark matter.

Experts believe that neutron stars may be “spitting out” these axions into space, and researchers are hopeful to measure them. The scientific community aims to uncover some properties and the nature of axions, such as their mass.

Since the 1970s, brilliant minds in physics have posited the existence of axions. They are somewhat similar to neutrinos, believed to interact with other matter via weak force, making them difficult to detect.

If axions exist at a certain mass range, experts could predict that their behavior is similar to dark matter, contributing to the mysterious effects of gravity.

Theoretically, axions quickly decay into pairs of photons when placed in a sufficiently strong magnetic field – which also makes them “invisible”. Based on this, scientists suggest that if a region has a strong magnetic field and an inexplicable amount of light, it is highly likely that axions have just decayed there.

Neutron stars are thought to be “spitting” out axions – (Illustrative image: NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center).

Neutron stars are renowned for their incredibly strong magnetic fields. Essentially, they are the cores of massive stars that have undergone a supernova explosion, collapsing into a hot mass with an extremely high density, exhibiting behavior akin to an atom but spanning several tens of kilometers.

The magnetic field emanating from neutron stars is hundreds of millions of times stronger than Earth’s magnetic field, strong enough to extinguish life.

Another variant of neutron stars, known as pulsars, possesses a very high rotation speed, and as they spin, their poles emit powerful radio radiation. Scientists compare these beams to the light emitted from a lighthouse, even suggesting the use of pulsars as “space lighthouses” for future journeys.

Pulsar Illustration – Image: ICRAR/University of Amsterdam

Last year, physicist Dion Noordhuis from the University of Amsterdam published a report suggesting that pulsars could produce over 50 axions per minute. As these mysterious particles leave the star, they move through the strong magnetic field and transform into photons, causing the pulsar to appear brighter than usual.

However, when analyzing some pulsars, researchers did not detect the expected excess light (indicating that axions did not decay there as previously assumed). Nonetheless, this does not confirm that axions do not exist around pulsars; perhaps there are limitations preventing the detection of signals from axions.

In the continuation of this research, scientists speculate that axions trapped in such a strong magnetic field would emit signals. Over time, possibly spanning millions of years, axions may gather near pulsars, coexisting with neutron stars and simultaneously emitting a soft glow like a layer covering the surface of the star.

If these axion clouds do indeed exist, they would be present around the vast majority of neutron stars. They would also have a significant density, generating detectable signals.

As of now, science is still unclear on what signals they could emit, and only two plausible hypotheses have been proposed.

The first suggests that the axion cloud would emit a continuous signal within the radio spectrum of the pulsar, with a frequency corresponding to the mass of the axion. While the exact mass number is unknown, the spectral limits could provide initial estimates.

The second possibility is that the signal will appear when a neutron star dies, exploding and ceasing to emit radiation. Naturally, this process typically takes hundreds of millions of years, and astronomers have yet to detect any neutron stars in such a state. According to experts, this possibility seems more plausible.

As for the excess light becoming a factor in identifying axions, scientists have not yet discovered traces indicating that axion clouds actually exist around neutron stars. However, this allows researchers to determine the limitations within which axions could form.

These studies help the field of astronomy gain a better understanding of this mysterious particle while providing new indicators and methods to help detect and measure axions (if they do indeed exist).

The study has been published in Physical Review X.