Humanity is all too familiar with the monumental contributions of figures like Albert Einstein, Louis Pasteur, and Charles Darwin. However, one significant character whose role in the course of human history is equally important yet often overlooked is the brilliant German scientist Fritz Haber.

This scientist was behind one of the most crucial inventions for human civilization, particularly in the field of agriculture. However, he was also the creator of one of the most dangerous weapons known to mankind at the time of its inception.

As a result, his legacy remains a starkly contrasting picture, showcasing the bright colors he brought to billions of people alongside the dark hues that envelop a crime that is hard to wash away.

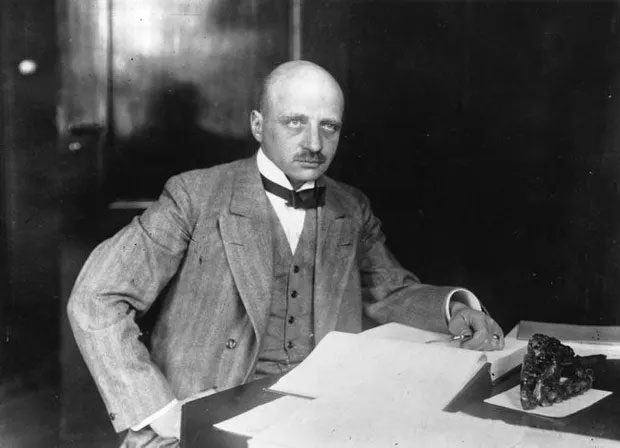

Scientist Fritz Haber

A Genius Who “Pulled Down” the Population Chart

The story begins with the most important invention of the 20th century—an discovery that continues to provide food for billions of people around the globe today. Haber was born in 1868 in the Kingdom of Prussia into a Jewish family. From an early age, he was obsessed with the idea of providing enough food for humanity as the population rapidly increased.

After studying at the University of Berlin, he transferred to Heidelberg University in 1886, where he studied under the famous German chemist Robert Bunsen. Eventually, Haber was appointed as a professor of physical chemistry and electrochemistry at the Karlsruhe Institute of Technology. When scientists of that time warned that the world would not be able to produce enough food to feed the growing population in the 20th century, he devoted his energy to this issue.

Scientists knew that nitrogen was essential for plant life; however, they were also aware that the supply of this element in a usable form on Earth was quite limited. But Haber discovered a method to convert nitrogen gas from the Earth’s atmosphere into a compound that could be used in fertilizers—NH3.

It is important to note that finding a way to produce nitrogen for fertilizers at that time was the “golden problem” of the century. To achieve higher crop yields, farmers began seeking ways to add nitrogen to the soil, and the use of manure, followed by bird droppings and nitrates, increased significantly. At one point, the value of bird droppings was exchanged at a rate of 4:1 for gold.

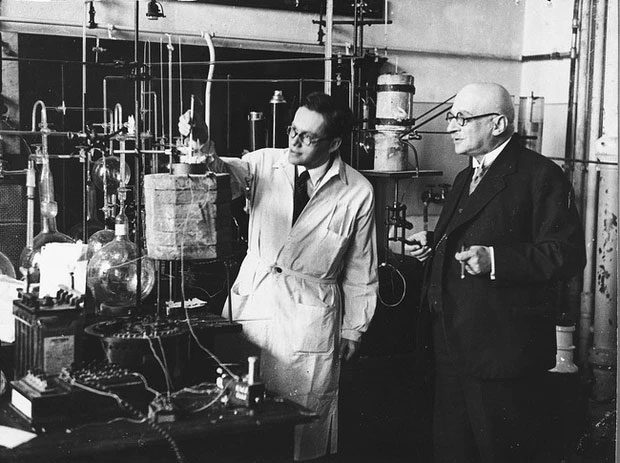

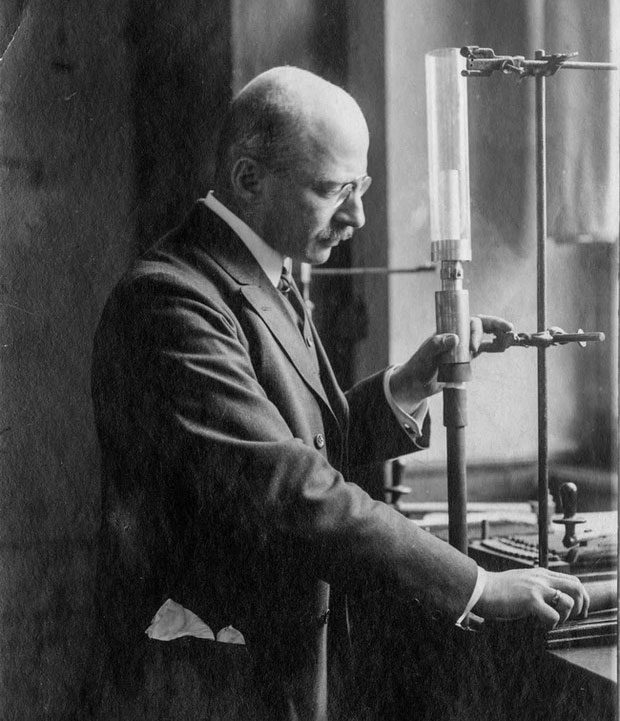

Fritz Haber created a homogeneous stream of liquid ammonia from hydrogen and nitrogen.

On July 2, 1909, Fritz Haber produced a homogeneous stream of liquid ammonia from hydrogen and nitrogen fed into a hot iron tube under pressure over an osmium metal catalyst. This was the first time ammonia was developed in this way.

This process is known as the Haber-Bosch process for synthesizing and producing ammonia from nitrogen and hydrogen. The suffix “Bosch” honors Carl Bosch for his industrialization of the entire process. Carl Bosch, a metallurgist and engineer, worked to refine this ammonia synthesis process for global use.

In 1912, the construction of a factory for commercial production began in Oppau, Germany. The factory was capable of producing one ton of liquid ammonia every five hours, and by 1914, it was producing 20 tons of usable nitrogen daily.

Today, chemical fertilizers contribute to about half of the nitrogen input in global agriculture; this figure is even higher in developed countries.

Currently, the regions with the highest demand for these fertilizers are also the areas experiencing the fastest population growth in the world. Some studies indicate that approximately “80% of the increase in global fertilizer consumption from 2000 to 2009 came from India and China.”

Even without considering the population growth in China and India, the influence of the Haber-Bosch process is evident in the chart below. It illustrates the significant impact of this discovery on the food supply that sustains humanity.

Population chart sharply rising since the invention of Haber. The vertical column represents the population in billions.

According to agricultural historian Vaclav Smil at a university in Canada, this process can be considered “the most important technological advance of the 20th century because it contributed to the food supply for half of the current population of the Earth.”

His achievements were recognized with the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1918, but met with fierce opposition from his colleagues in the scientific community.

The “War Criminal”

Haber’s career flourished, and around the beginning of World War I, the German Army requested his assistance in developing a method to replace explosives in shells with toxic gas.

Unlike his friend Albert Einstein, Haber was a fervent German nationalist, and he was willing to become an advisor to the German War Office. During World War I, he began experimenting with the use of chlorine gas as a weapon.

During World War I, he began experimenting with the use of chlorine gas as a weapon.

By 1915, failures on the front lines intensified Haber’s determination to use chemical weapons, despite the terms of the Hague Convention prohibiting chemical agents in warfare.

Haber faced difficulties in finding any German military commanders willing to participate in a field test. One general described the use of poison gas as “cowardly”; another declared that poisoning the enemy was “abhorrent.” However, if it came with victory, that general was willing to “do what needed to be done.”

According to biographers, Haber at that time implored the military to use chemical weapons to achieve victory.

In 1915, Haber personally appeared on the battlefield at Ypres to oversee the use of toxic gas against the Allied forces. Waiting for the right moment when the wind was favorable, the Germans released 160 tons of chlorine gas from thousands of cylinders towards the enemy at dawn on April 22.

The result was that over half of the 10,000 enemy troops died immediately from asphyxiation. The survivors endured hell on earth with bodily torment.

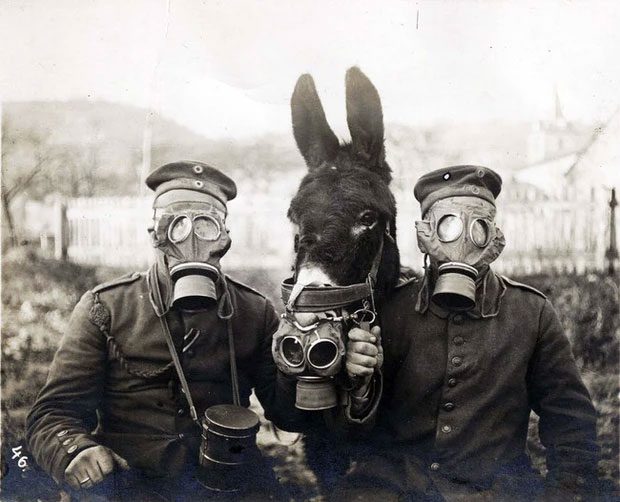

Haber’s weapon led to the widespread use of gas masks on World War I battlefields.

The horrific casualties caused by this weapon even made the Germans suspicious of the rapid retreat of the enemy. The Second Battle of Ypres witnessed nearly 70,000 casualties among the Allies, but the Germans suffered even greater losses as it was the first large-scale use of chemical weapons.

Fritz Haber was soon promoted to captain, and on May 2, 1915, he returned home to Berlin to attend a banquet in his honor. The next day, he would head to the Eastern Front to initiate another gas attack against the Russians.

An Endless Tragedy

By the end of World War I, the chemical weapons of the Germans had largely been neutralized due to the development and widespread use of gas masks among the Allied forces. However, Haber and the researchers involved were heavily criticized by both sides: the Germans for their defeat and the Allies for employing inhumane weapons.

Haber’s life may serve as a classic example of the saying “talent and misfortune go hand in hand.” On the day he returned to Germany for the banquet following the battle of Ypres, his first wife—a chemist herself—committed suicide. She had long been under stress from raising their child and vehemently opposed her husband’s wartime research direction.

As anti-Semitism escalated in Germany, he lost his job.

But the tragedy did not stop there. After the death of his first wife, Haber experienced a seismic shift in his life and career, finding little success until the early 1930s. As anti-Semitism escalated in Germany, he lost his job.

Later, Haber wandered across Europe seeking a place to settle, but of course, this was impossible as he was condemned everywhere for his past crimes. Haber died in 1934 in a hotel in Switzerland, without having the chance to repent for his mistakes.

The issue is that the consequences of his talent continued for many years thereafter. Around the 1920s, Haber and his associates succeeded in researching pesticides containing hydrogen cyanide—an extremely toxic substance.

This research was later industrialized under two product lines: Zyklon A and Zyklon B. By World War II, Zyklon B became a powerful tool in the extermination of Jews in concentration camps – victims included even Haber’s relatives. This may be his bitterest legacy, or perhaps that of any scientist from the previous century.

“The life of Haber is the tragedy of German Jews – the tragedy of unrequited love.” This was the observation made by Einstein, a friend, fellow Jew, and colleague in the scientific community regarding Haber.