Scientists at Curtin University (Australia) from an international research team have investigated an ancient volcano in Indonesia.

The research team discovered that the volcano remains active and dangerous thousands of years after an eruption. This is seen as a sign that scientists need to reconsider how to predict these potential catastrophic events.

According to Associate Professor Martin Danisik, the lead author of the study from the John de Laeter Center at Curtin University, supervolcanoes typically erupt after periods of tens of thousands of years. However, the research team is uncertain about what happens during the time the volcano is dormant.

A supervolcano eruption is one of the most catastrophic events in Earth’s history.

“Understanding these periods of inactivity will define what we look for in younger, active supervolcanoes. This will help us predict future eruptions,” Associate Professor Danisik stated.

According to Danisik, supervolcano eruptions are among the most catastrophic events in Earth’s history, releasing enormous amounts of magma. These eruptions can affect the global climate to the extent of plunging the Earth into a state of “volcanic winter” – an unusually cold period.

“Understanding how supervolcanoes operate is crucial to grasping the future threat of an inevitable super-eruption, which occurs approximately once every 17,000 years,” the expert noted.

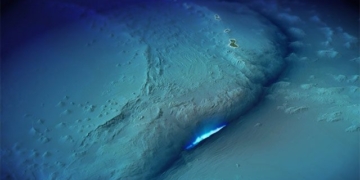

The research team studied magma following the eruption of the Toba volcano 75,000 years ago.

“Using geological time data, statistical inference, and thermal modeling, we demonstrated that magma continued to flow within the volcano’s caldera, or the deep depression created by the magma eruption, for 5,000 to 13,000 years after the eruption. Subsequently, the remaining magma crust solidified and was pushed upward like a giant turtle shell,” Associate Professor Danisik explained.

According to this expert, the new findings challenge existing knowledge and research on eruptions. Scientists often continuously search for liquid magma beneath volcanoes to assess future hazards.

However, the research team currently believes that the possibility of eruptions occurring even without liquid magma beneath the volcano must be considered.

Danisik emphasized that understanding when and how magma accumulates and its state before and after an eruption is extremely important.