The Forbidden City is the largest complex among the well-preserved historical sites in the world, comprising 800 structures with 9,000 rooms. It serves as a tranquil oasis located right in the heart of bustling Beijing, China. Today known as the Palace Museum (Gu gong), it was previously called the Forbidden City (Zi jin cheng) because it prohibited commoners from entry unless granted permission.

The fundamental principles of Chinese construction link these buildings to China’s ancient past. The structure is a prime example of traditional Chinese architecture, featuring a wooden frame that supports the weight of the roof, constructed using a complex support system, with eaves extending out from the curved walls, sloping rooftops, decorative tiles, and infill of bricks and stones within the walls.

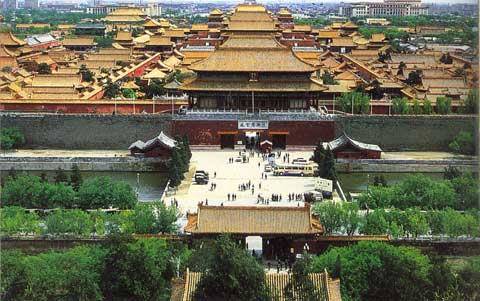

A panoramic view of the Forbidden City illustrating a vast area and

numerous distinct structures with golden roofs and red walls.

For over 500 years, from its completion in 1421 until 1925, when it became a museum, the Forbidden City served as the administrative center of the government and the residence of 24 emperors of the Ming and Qing dynasties. The last emperor of China, Aisin Gioro Puyi, lived here until he was five years old as emperor and was confined within the Forbidden City again after the establishment of the Republic in 1911. However, he was ultimately forced to flee to Tianjin in 1924. The following year, the Forbidden City was converted into a museum.

Today, it stands as the largest museum in the world, belonging to the most populous nation, housing China’s most important artistic treasures, relics, and paintings, attracting up to 10 million visitors annually. In 1987, UNESCO declared the Forbidden City as a World Cultural Heritage site.

Construction History

The construction of the Forbidden City began in 1406, under the orders of Emperor Yongle, Zhy Di—a powerful general and cunning political strategist—who seized the throne from his nephew with forged evidence during a bloody civil war. Initially, Emperor Yongle retained the existing capital in Nanjing, but soon realized that southern regions might not be loyal, prompting him to move the capital north to Beijing, closer to his own power base. The new palace was built on the site of the former Yuan dynasty palaces, which had been destroyed by the first Ming emperor, Hongwu, during his conquest of the Mongols.

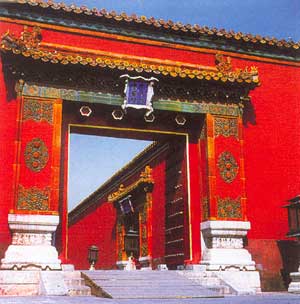

|

| Ceramic-tiled gate, inscribed with Chinese and Manchu script. |

The structures seen today date primarily from the 15th century. Because the buildings are primarily made of wood, several fires have caused significant damage, necessitating extensive renovations throughout the 600-year history of the Forbidden City. For example, Emperor Qianlong (around 1736 – 1796) renovated, rebuilt, and expanded the Forbidden City, adding magnificent parks and the Nine Dragon Screen, measuring 27.5 meters long and 5.5 meters high, decorated with colored ceramic tiles. His son and successor, Emperor Jiaqing, who reigned from 1797 to 1799, also rebuilt three main halls after they were damaged by fire.

Orientation and Color Selection

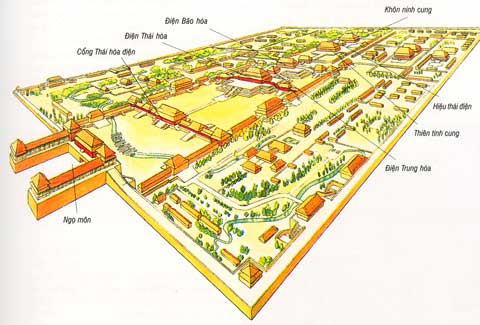

According to traditional Chinese architectural orientation principles, the Forbidden City is symmetrically arranged along the north-south axis. Jingshan Hill (jing shan), formed from the earth excavated from a wide moat surrounding the palace complex, lies to the north, while Tiananmen Square is situated to the south. The area of the complex is equivalent to more than 100 football fields. It is essentially composed of a series of structures arranged in two main sections: the front palace facing south (Qian Chao) and the inner palace (Nei Tang) facing north.

The front palace consists of three grand halls built on a three-tiered marble base, used for military and civil ceremonies as well as imperial audiences. The inner palace surrounds three large palaces set on a single-story foundation, serving as the emperor’s residence, with other less formal palaces designated for royal family use, as well as storage, libraries, parks, and shrines for ancestral worship.

Water is supplied from a reservoir located in the northwest, flowing south into the complex, where a beautifully carved marble bridge crosses over it. Protecting the Forbidden City is a wide moat and a thick wall made of rammed earth mixed with bricks, featuring large arched entrances at the cardinal directions and tall watchtowers at the four corners.

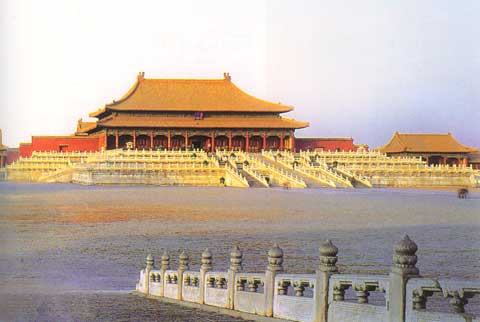

Crossing a vast space, the Hall of Supreme Harmony is located at the top of two flights of marble stairs and a pathway used for the emperor’s palanquin, guarded strictly with carvings in the center.

The open space emphasizes the large scale of the complex as visitors travel from south to north, while the lower buildings on the sides highlight the grandeur of the three audience halls within the palace. The first of these is the Hall of Supreme Harmony (Taihedian), the largest and most impressive residence in the complex, covering an area of 2,730 m2, equivalent to 9 tennis courts, measuring 64 meters in width and 37 meters in length. The scale, shape, decoration, and interior woodwork of the hall all convey a sense of authority and superiority of the emperor over all others summoned for ceremonies marking adulthood, announcing civil examination results, and welcoming newly appointed officials.

Throughout the Qing dynasty (1368 – 1644), the Forbidden City was utilized during three major festivals:

|

|

Patterns on the Nine Dragon Screen. |

Chinese New Year, the Emperor’s Birthday, and the Winter Solstice. For special occasions, the courtyard of the Hall of Supreme Harmony could hold up to 100,000 people, including soldiers in uniform and numerous court musicians. During such times, the atmosphere was infused with the scent of incense burned in large braziers. Behind this hall, the Central Hall, known as the Hall of Central Harmony (Zhonghe dian), was used for preparing major ceremonies. The final administrative building, the Hall of Preserving Harmony (Baohe dian), was where lavish banquets were held and where scholars sat for national examinations; passing these exams ensured a favorable career within the imperial bureaucracy.

From this hall, two staircases slope down the center, carved with nine dragons chasing pearls on clouds, symbolizing auspiciousness. The emperor was carried above this symbol of authority and fortune by his palanquin bearers. The sloping path was crafted from Fangsan marble, weighing around 200-250 tons. The installation demonstrated the emperor’s access to resources and his workforce. It required 20,000 people working for 28 days to drag this stone over 48 kilometers to its installation site. Scholars suggest this work was conducted in winter when it was possible to create an ice road for sliding the stone.

Facts and Figures:

-

Area: 250,000 m2

-

Moat Width: 54 m

-

Wall Height: 10 m

-

Number of Structures: 800

-

Number of Rooms: 9,000

-

Workforce: estimated at 1,000,000

In addition to the official halls, there are three other palaces. The first palace, the Palace of Heavenly Purity (Qian qing gong), was the official residence of the Ming emperors. Here, in 1542, the emperor

|

| Details of the muted yellow tiles in the Forbidden City |

Emperor Jiaqing’s reign was marked by a lack of popular support, especially after an assassination attempt by a group of palace maids who tried to strangle him but failed due to poorly tied knots. Once betrayal occurred, all involved faced execution. The second palace, Jiao Tai Dian, was used to receive birthday wishes from concubines and princesses and also served as the storage for 25 imperial seals dating back to 1746. Kunning Gong was the sleeping quarters for the Empresses of the Ming dynasty. The last Empress of the Ming dynasty committed suicide here as the Manchu army approached. Later, during the Qing dynasty, this space was used as a bridal chamber for three nights following a wedding. On either side of this room are the East and West Six Palaces, where concubines and other royal family members resided.

Unlike contemporary palaces built in the West, the Forbidden City boasts an incredible array of colors when viewed from the outside, featuring red walls, purple columns, and roofs that curve upward adorned with shimmering yellow ceramic tiles and various decorative motifs. The clay tiles are laid in a crescent shape, inspired by cut bamboo shoots, alternating between Yin (upward tiles) and Yang (downward tiles). The tiles cover the ends of the sloping roofs, often shaped like dragons to symbolize protection. The colors on the roofs, walls, and columns are further enhanced by the use of granite and light gray bricks for the flooring between structures.

Lavish banquets of the imperial court were regularly held in the Forbidden City. In 1796, over 5,000 guests aged 60 and above were invited to dine at 800 tables to celebrate the transfer of power from Emperor Qianlong to Emperor Jiaqing.

Recreation of the Forbidden City showcasing key elements.

“No capital city among our European capitals has been conceived and designed with such overwhelming splendor, especially with the intention of conveying an impression of the emperor’s majesty and grandeur.” – Pierre Loti, 1902.