-

Construction Period: from 1569 – 1575

-

Location: Edirne, Turkey

The Selimiye Mosque in Edirne is a masterpiece by one of the most renowned architects in world history – Mimar Sinan. His peak experience is evident in its timeless shape, intellectual structure, and magnificent space at an unmatched level. Sinan strove to achieve a unity that balances durability with elegance, visual stimulation with spiritual tranquility. Edirne represents the pinnacle of his career.

The Architect and His Masterpiece

Sinan was born in a modest village in present-day Central Anatolia that bears his name. Starting as a carpenter, he was conscripted into the Janissary corps, an elite infantry unit, and shortly after, his superiors were astonished by his ability to construct roads, bridges, and build embankments in the shortest time. He also served as a commander on the battlefield, and his tomb inscription honors the time he served in the military and the construction of the Buyukcekmice Bridge over the marshes on the route from Istanbul to Edirne.

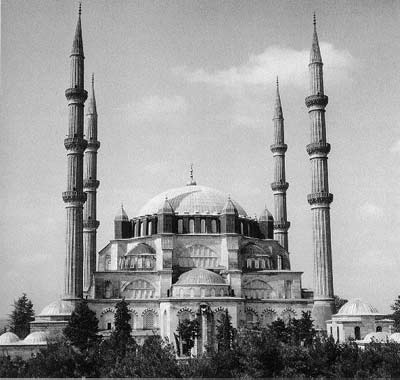

Sinan’s Masterpiece: The mosque for Sultan Selim II has 4 minarets,

the tallest in Islam, and a semi-dome that supports the main dome’s thrust (Photo: fa.org)

Upon retiring as a general, Sinan quickly became the chief architect and effectively served as the Minister of Public Works. He held this position until his death at the age of 96-100 in Islamic years, mentoring many generations of architects. He began the construction of the Selimiye Mosque when he was 80 years old.

Selim II was both a poet and a progressive patron who delegated the rule of a vast empire to Grand Vizier Sokollu Mehmet Pasha, who was also an aesthetician. With no more hills available for building a mosque for the Sultan in Istanbul, he chose the remaining high ground in the summer palace in Edirne, rich with rivers, meadows, and lush forests.

Travelers from Greece to Edirne will find a unique silhouette of domes and minarets in the mosque that stands out against the sky, with the Selimiye Mosque and its four minarets dominating the view. From Istanbul, the mosque can be seen from 10 km away, reminiscent of cathedrals in Europe, with a diameter of 31 meters; its dome rivals that of the Hagia Sophia in Istanbul, which has been considered the largest cathedral in the world for thousands of years. The downward thrust is crucial for a dome as the structure tends to expand outward. In Edirne, two semi-domes bear the thrust, primarily transferring it directly to the supporting piers. Sinan resolved this structural issue during his first construction of a mosque for Suleiman the Magnificent in Istanbul.

The basic structure consists of limestone blocks proportioned in Roman style, quarried using sand dust, repeated in Edirne. However, Sinan made a groundbreaking innovation by removing the main supporting pillars and replacing them with eight piers that serve as wall supports, with corresponding minarets above. Sinan also took pride in the four minarets, each reaching 71 meters, making them the tallest in Islam.

During the preparation for construction, Sinan’s military precision proved invaluable. Every type of material needed for construction had to be ordered, then assembled, and stored in sequence according to its usage. Most of the stone was sourced locally, but the marble columns were brought from across the Ottoman Empire. Additionally, carved shutters, window frames, and other details, including iron grilles and arch supports, were required.

Labor costs for each worker, aside from the soldiers hired by the army, included many skilled craftsmen from villages specializing in carpentry, carving, and plumbing. During the three winter months when shipping was impossible, slave labor was employed. A total of 20,000 people were mobilized, along with those caring for horses and donkeys. This explains how the structure could be completed in just six years.

Exterior and Interior

Outside the mosque, a spacious courtyard occupies an area equal to that of the interior. The large arch traditionally positioned at the grand entrance features a rhythm created by the insertion of a pair of smaller arches, adorned with plates inscribed with phrases that can be interpreted as celestial symbols. There are impressive colonnades along the sides, with a handwashing fountain placed in the center, all completing the courtyard without needing an additional dome.

With gilded wrought iron grilles and polished marble – most beautiful after each rain – the open space is only comparable to the distant view through the doorways on either side. The mosque’s side is carved deeply to create shadows at the entrance and in the arched wall niches – this is crucial for accurately assessing the interior, which represents a revolution in Ottoman architecture.

The entire space is utilized by removing the main supporting pillars. This action is enhanced by the shadow effect at ground level, created by the recessed windows from the outside, designed to reduce light entering the lower areas inside. Faith and life are thus divided in this manner – the balcony extending above the height of the wall niches with many large windows still allows unobstructed light to flow as well as the windows on the upper levels.

(Photo: fa.org)

For the first time, a large platform for the muezzin to announce prayer times was placed directly beneath the center of the dome, with a fountain below symbolizing life, which is quite unique. The rich paintings along the edges of this platform are in perfect condition. The white marble mimbar, or pulpit, serves as the focal point of all prayer gatherings as it indicates the direction of the holy city of Mecca. There are large windows to create light in the sacred space, and the restrained decoration in the prayer hall gives way to the celestial floral-covered walls, fully utilizing colors from the lime kilns in Iznik at their finest. Elsewhere, aside from the outer corridor designated for the Sultan, the use of ceramics is limited. In the corners of the supporting arches, meticulously curved tiles fit into uneven spaces resembling bouquets, satisfying the designer in the palace workshop completely.

At night, many candles beside the mimbar are lit, with smoke trapped in brass caps creating the finest black ink. The congregation faces the main hall, and the low ceiling shimmers with soft lights, cutting the space with an invisible sanctity. Records regarding the mosque’s foundation indicate that two officials were tasked with preventing others from digging here for olive oil during the time before electricity. Records also note that the muezzin had to marry a beautiful young woman to ensure he was never seduced by anyone else.

To achieve the ultimate glory of the Sultan’s corridor, a wide staircase leads into the thick wall to an entrance tiled with ceramics leading into the splendid room adorned with the finest ceramic tiles – one tile was stolen by Russian troops during their invasion in 1878 and is currently housed in the Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg. The tiles gradually ascend to the highest point in the small wall niche leading to the mihrab. This is a resting place for worshippers, and the period of abstinence lasts up to 40 days. No ruler can be absent for so long; 40 is a magical number, thus turning days into hours. The mimbar is an impressive piece crafted from a different type of wood by Sinan – the wall itself serves as a shutter, allowing a Sultan to kneel and pray directly to heaven. This is an emotional moment that no architect has ever reached before.

The Sultanate ended in 1924, but the mosque continues to thrive as the most important landmark outside Istanbul in modern Turkey. The structure has been surveyed recently and found to be in very good condition despite previous looting by Russian forces. No architect, not even his senior pupil Mehmet Agha, can compare to Sinan in terms of talent and imagination. By perfecting the Ottoman achievements, Sinan made it impossible for there to be a creative heir within the same tradition. History never unfolds differently.