MIT and Invena are testing submerged structures to collect sand, protect the islands of the Maldives, and even create new islands.

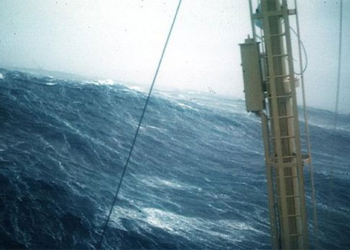

The third field trial by the MIT Self-Assembly Lab and Invena took place at the end of 2021, using lightweight, low-cost structures that can be quickly deployed and easily adjusted. (Video: MIT Self-Assembly Lab/Invena).

Globally, coastlines are threatened by rising sea levels and increasingly intense storms. Many island nations and coastal cities are taking action to save themselves, from building sea walls to dredging sand from the seabed and pumping it onto beaches. However, these interventions can be costly, challenging to maintain, and harmful to ecosystems.

In the Maldives, a nation consisting of approximately 1,200 islands forming a 900km chain in the Indian Ocean, the MIT Self-Assembly Lab and Invena are researching a more natural solution. By utilizing submerged structures, the team of experts harnesses ocean forces to allow sand to accumulate in carefully selected locations to protect the Maldives and potentially create new islands.

Initially, the scientists experimented in the wave tank at MIT in Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA. To determine the ideal orientation and shape of the submerged structures, they analyzed data on ocean waves and currents from sensor systems in the Maldives, tide and weather data, thousands of computer simulations, and a machine-learning model trained on satellite images to predict sand movement.

Since 2019, MIT and Invena have conducted field trials in the Maldives, where the coastlines of most islands are eroding. With an average elevation of only 1 meter above sea level, this is the lowest country in the world.

The trials, primarily conducted in the shallow areas of a coral reef south of the capital Malé, are quite diverse. They include submerging a tightly bound network of ropes to collect sand and using a material that transforms from fabric into solid concrete when sprayed with water to create underwater barriers that help accumulate sand. In another trial, the team established a floating garden on a sand strip to investigate whether tree roots could help stabilize the collected sand and gather more.

A naturally formed sand strip at an elevation of about 1 meter above sea level in the Maldives. (Video: MIT Self-Assembly Lab/Invena).

With each field trial, the research team learns more about which materials, structures, and building techniques can make sand accumulation simple, cost-effective, sustainable, durable, and scalable. So far, the second field trial, initiated in 2019, has shown the most promising results. This trial involved placing biodegradable fabric bags filled with sand in strategic locations to create a sand strip.

In just four months, approximately 0.5 meters of sand has accumulated over an area of 20 x 30 meters. Currently, this sand strip stands about 2 meters high, 20 meters wide, and 60 meters long. The materials used are expected to last around 10 years, being more durable and cost-effective compared to dredging and pumping sand methods, according to Skylar Tibbits, founder and co-director of the MIT Self-Assembly Lab.

In the near future, Tibbits believes that the lessons learned will help effectively replenish beaches and islands. The longer-term goal will be to construct new artificial islands.