This fish species has prompted at least three countries to collaborate in seeking solutions to control them.

An alliance of biologists and engineers from the University of Western Australia, New York University (USA), and the University of Padova (Italy) has come together to tackle a small fish species that poses a significant threat to native species in these three countries. The fish causing headaches for scientists in these countries is the mosquito fish, a freshwater fish. After a period of research, they decided to rely on its natural predator, the Largemouth Bass. Initially, scientists have created several robotic fish modeled after the shape and movement of the Largemouth Bass to test their effectiveness in chasing the mosquito fish. So, what makes the mosquito fish so alarming that experts are resorting to robots to combat them?

The mosquito fish is the “culprit” that has led scientists to enlist robots to curb their invasion. (Photo: Pixabay)

What is the Mosquito Fish?

The mosquito fish, also known as the mosquito-eating fish or Gambusia affinis, belongs to the Poeciliidae family, along with the guppy, and gives live birth (i.e., it bears live young). The name “mosquito fish” derives from its diet, which consists of mosquitoes and mosquito larvae. Additionally, they often consume zooplankton, beetles, winged insects, and various invertebrates; mosquito larvae constitute only a small portion of their diet.

The mosquito fish is very small and slender, resembling willow leaves. Its body is bright yellow with a slight blue sheen, and its belly is swollen. Adults can grow up to 8 cm in length, though most are around 5 cm long. They have tiny teeth, a slightly pointed mouth, and large eyes, and are classified as livebearers. The dorsal and ventral fins are located near the base of the tail. Males have long reproductive organs, while females possess shorter, rounder ones.

The mosquito fish is a freshwater fish specialized in hunting mosquito larvae and mosquitoes. (Photo: Pixabay)

The mosquito fish thrives in water temperatures of 18-28°C. This fish species can produce sound using swim bladders. They are relatively aggressive, often attacking fish of similar sizes. During the day, they usually dive to the bottom, coming up at night to forage. In April and May each year, they begin migrating to nearshore areas to prepare for breeding. Mosquito fish lack a stomach, possessing a short and primitive digestive tract, allowing them to consume a large number of larvae compared to their body size.

The mosquito fish gives live birth, with a large number of offspring and a very short breeding cycle. The fry reach maturity in about one month and begin breeding again. Their breeding season lasts from April to October, primarily between May and September. Each breeding cycle occurs every 30-40 days, producing 30-50 fry at a time.

The mosquito fish gives live birth, producing a large number of offspring during each cycle. (Photo: Pixabay)

In colder seasons, when water temperatures drop, mosquito fish typically seek shelter in dense vegetation or burrow into the mud. They can survive even in low-oxygen conditions. When spring arrives, and mosquito larvae and plankton begin to thrive again, the fish emerge from their hiding spots, with abundant food available to prepare for breeding.

The mosquito fish has remarkable adaptability and is easy to care for. Originally from Central America, its effective larvae-eating habits have led to its introduction in various regions around the world.

A Fish Honored with a Bronze Statue

There are over 40 species of mosquito fish in nature. They primarily inhabit freshwater regions but can also survive in slightly brackish environments. They thrive in natural and artificial lakes, ponds, and river mouths, even in roadside puddles. If a mosquito fish feels threatened, it will hide in the ground out of fear and can even change gender temporarily (within two to three weeks).

This fish can change gender temporarily when frightened (within two to three weeks). (Photo: Pixabay)

The mosquito fish is quite resilient, capable of living in weakly acidic water or water with a 3% salinity. Even in water with nearly zero oxygen levels or often lacking oxygen, they can still thrive. They can survive temperatures ranging from 4.5 to 40 degrees Celsius, though the ideal range is 18 to 30 degrees Celsius.

At stable temperatures, a mosquito fish can consume 40-100 larvae daily, with a maximum of up to 200. They are well-known as natural enemies of mosquitoes. Thanks to mosquito fish, the spread of malaria has been curtailed. The city of Sochi in Russia erected a bronze statue to honor the mosquito fish that has kept their locality free of malaria cases for over 60 years.

In Australia, mosquito fish often nibble on the tails of native tadpoles, causing their demise. (Photo: Pixabay)

While mosquito fish were once welcomed in many countries, their rapid proliferation and significant damage have led many nations to seek ways to control them.

For instance, in Australia, mosquito fish began to multiply excessively and eliminate other fish species, resulting in an ecological imbalance. Consequently, government officials decided to ban the breeding and sale of mosquito fish.

In countries such as Australia, the USA, and Italy, mosquito fish often nibble on the tails of other fish and tadpoles, preventing these species from accessing food. Without tails, these creatures cannot swim and compete for food with mosquito fish. Unable to forage, native species face starvation. Mosquito fish also exert pressure on other populations by consuming fish and frog eggs.

Countries have traditionally used traps and chemicals to control this fish species but with little success. (Photo: Pixabay)

The mosquito fish not only consumes specialized dry mixtures for ornamental fish but also eats bloodworms, mosquito larvae, and other insects captured in their habitat. Their population has surged across freshwater lakes and rivers worldwide, creating serious problems for native fish and amphibians. They compete for food and habitat, diminish genetic resources, destroy or degrade habitats, transmit diseases and parasites, causing significant losses in biodiversity, economic impact, health issues, and reduced agricultural productivity. Countries have traditionally used traps and chemicals to control mosquito fish but have failed, sometimes harming native species instead.

Employing Robotic Fish to Combat Invasive Species

As a result, scientists from the USA, Australia, and Italy have developed robotic Largemouth Bass made of rubber mounted on a vertical shaft with a magnet at the bottom. The robot is placed in a water-filled tank, with another magnet positioned underneath that attaches the robot’s magnet to the bottom of the tank. Scientists utilize motors and devices to move the magnet, allowing the robot to maneuver in various directions.

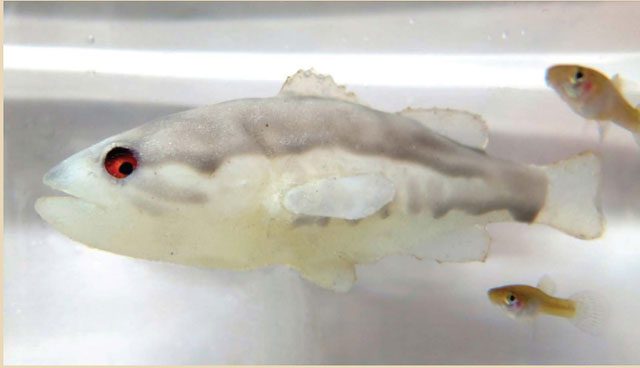

Close-up of a robotic fish designed to hunt the invasive mosquito fish. (Photo: Pixabay)

The robotic fish is programmed to provide real-time feedback and mimic predatory behavior by swimming faster. During a five-week trial, mosquito fish being pursued by the robot showed increasing reluctance to approach tadpoles. This behavior persisted even when the robot was not present. The mosquito fish exhibited signs of stress and weight loss when chased by the robot. Their bodies became thinner, and their reproductive capabilities diminished. These factors will negatively affect the survival of mosquito fish in the environment.

Nonetheless, a representative from the expert team stated: “Although successful in deterring mosquito fish, the robotic fish is not yet ready for release into the wild.” They also hope that using robotic fish to expose the vulnerabilities of the mosquito fish will pave the way for enhancing biological control efforts against invasive species.