From water clocks, inventors sought to create another device for measuring time. The first person to create a mechanical clock was the monk Gerbert, an astronomer. This Benedictine priest invented the “escapement” mechanism in 996. At that time, the machinery of clocks was quite complex. They were powered by a heavy weight, making the clocks large and bulky. Initially, clocks were equipped with a bell, and the chimes reminded the monks of prayer times. This led to the Latin term “clocca” and the English term “clock.”

|

|

The pendulum of the pendulum clock |

In 1288, a large clock that struck the hour and chimed several times a day was installed on the tower of Westminster Hall in England. It is also said that King Henry VIII, while in debt, ordered the bells to be removed and sold to pay off his loans.

The technology of clocks gradually improved, and by the 14th century, clocks could be found everywhere. At that time, there were many styles of clocks, but they were all large and powered by weights over 50 kg. Some had a 24-hour face that rotated in front of a fixed hour hand. During this period, the most famous clock belonged to King Charles V. The first astronomical clock was constructed by Abbot Richard Wellington for St. Albans Cathedral between 1326 and 1344. Another clock, made by Henry De Vick from Württemberg, Germany, was created for the royal palace in Paris (now the Palais de Justice), featuring a single hour hand and a weight of 227 kg (about 500 pounds) falling from a height of 9.8 meters (32 feet).

Due to the utility of clocks, many people began commissioning clockmakers, leading to the further development of this craft. While large, bulky clocks became common, nobles and wealthy individuals desired smaller, portable clocks for personal use. Thus, efforts were made to create wearable timepieces. The first “neck clock” was made by Peter Henlein in Nuremberg, Germany, and was imitated by other clockmakers. Henlein used a spring as the driving force for movement. With his abundant imagination, he created a clock resembling the shape and size of an egg, which led the public to call it the “Nuremberg Egg.” This type of clock was very expensive, and it is said that the Marquis De Laborde purchased one for 26 gold coins in 1377.

By the late 14th century, clocks became a form of expensive jewelry. People often wore a gold chain to display their clocks at their chests. With various styles of clocks, the methods of use also differed. In 1520, Father Frederic Pistorius, the Prior of Nuremberg, gifted a clock to Martin Luther. Luther expressed his gratitude with the words: “. . . this gift is truly valuable. I must consult mathematicians to understand how to make and use this clock because I have never seen one like it before.”

From the 16th century, European clockmakers worked diligently to create increasingly smaller and more aesthetically pleasing clocks, often adorned with diamonds, and using precious metals for the clock cases. At that time, while nobility took pride in their pocket watches, churches boasted large clocks mounted on their facades.

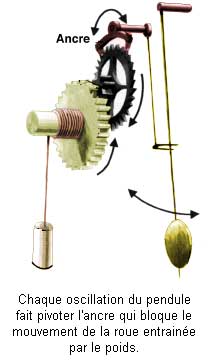

In the 17th and 18th centuries, a series of scientific inventions increased the accuracy of clocks and reduced the weight used in clock mechanisms. In the early 17th century, Galileo described the properties of the pendulum. The pendulum’s motion intrigued physicists. On July 16, 1675, Christian Huygens, a Dutch physicist and astronomer, presented the first pendulum clock to the Dutch government, and on December 30, 1675, he published his invention of the spiral spring. This invention greatly benefited the clock industry and promised scientists a tool that could accurately measure short periods like seconds.

|

|

The type of clock made by Peter Henlein |

In 1676, another significant improvement was made: the English physicist Robert Hooke invented the anchor escapement. This mechanism was initially used for clocks set up at observatories, but later, a clockmaker named Thomas Tompion adopted it for the clocks produced by his family.

Robert Hooke’s innovation in clocks was promising, but it had one flaw: in the anchor escapement, a phenomenon called “kickback” occurred, which affected the clock’s accuracy. Therefore, in 1715, George Graham improved clock mechanisms with a type of escapement known as “deadbeat.” With suitable modifications, pendulum clocks became accurate instruments by 1800.

Initially, spring-driven clocks still had many flaws. The springs weakened over time, and the pendulum’s movement was uneven when the clock was tilted. Although from 1550, cogwheels were made of brass instead of iron, clocks still did not tell time accurately; thus, even with the addition of a minute hand, many people did not pay attention as clocks could be off by half an hour to two hours during this period.

On land, Huygens’ pendulum clock worked perfectly when hung on walls but was unsuitable for the swaying of ships, which concerned many mariners. In 1598, King Philip III of Spain offered a large reward for anyone who could invent a clock usable at sea, but no one claimed the award.

In previous centuries, sailors went to sea without knowing their longitude, resulting in thousands of ships, people, and tons of cargo getting lost each year. Despite having mapped out the meridians, no one had found a way to determine longitude. Latitude was less challenging to ascertain. Mariners often used a sextant to measure the altitude of the sun or known stars and then referred to altitude tables to find results. However, determining longitude was significantly more difficult. For latitude, people relied on the equator, while longitude consisted of imaginary lines connecting the poles without any fixed reference point. In 1675, King Charles II of England established the Royal Observatory at Greenwich to “seek the longitude of locations to improve the fields of navigation and astronomy.” Nevertheless, the meridian through Greenwich was only accepted as the prime meridian much later, in 1884.

Since the advent of clocks, mariners placed their hopes in this time-measuring device to deduce the longitude of a place. As the Earth rotates 360 degrees in 24 hours, it is possible to compare the local time of one location with the time at a place with a standard meridian to deduce longitude. By the 17th century, the number of ships at sea had increased significantly, yet no method had been developed to determine coordinates at sea. Due to navigational errors, many ships encountered disasters, the most severe being the British fleet commanded by Sir Cloudesley Shovel, which strayed off course and struck a reef near the Scilly Islands. Approximately 2,000 sailors lost their lives in this disaster in 1707. Following this calamity, the British Parliament announced a reward of £20,000 for anyone who could invent a chronometer for maritime use. Numerous designs and blueprints for this device were submitted to the Navy, but none met the requirements.

It was not until 14 years after the British Parliament announced the prize that John Harrison from Yorkshire presented a spring-driven and pendulum-based chronometer. A panel reviewed Harrison’s proposal, and he was encouraged to build a prototype of this clock. At 42 years old, Harrison presented his first chronometer but only received a nominal prize, as the British Navy demanded a more accurate timepiece from the inventor.

At the age of 66, Mr. Harrison presented all four of his timepieces to the Board for review. During a journey to the Caribbean islands, Harrison’s fourth timepiece performed remarkably well, being off by only 5 seconds, meaning users could miscalculate by merely 1 nautical mile, compared to previous errors that could be as much as 100 nautical miles. By the age of 76, despite suffering from severe vision impairment, Harrison presented yet another timepiece design but received only an uncertain promise from the Navy for a £20,000 reward. At this point, the inventor had lost patience and requested an audience with King George III. The King listened attentively to Harrison’s passionate account of his long wait for recognition. John Harrison dedicated his entire life to the accurate determination of longitude, and at the age of 80, he finally received the award. Three years later, John Harrison passed away. By the end of the 18th century, many were still attempting to create timepieces. In France and Switzerland, engineers made significant progress, notably Thomas Earnshaw’s improvements in 1781, an English watchmaker.

In the 17th century, clocks had minute and second hands; by the 18th century, jeweled bearings were introduced to reduce friction and increase the longevity of timepieces. The craftsmanship of clock-making required exquisite and precise components, leading to the gradual establishment of guilds to protect the rights of craftsmen. The Paris Guild of Clockmakers was founded in 1544, followed by the establishment of the Clockmakers Company in London in 1630, which still exists today. The Netherlands, Germany, and Switzerland also gained reputations for producing beautifully and mechanically perfect clocks.

In the 16th century, pocket watches were commonly used, but no one thought to create wristwatches. Eventually, wristwatches were invented, though the exact origin remains unclear. One story suggests that one sunny morning, a woman watching her child in a park in Geneva wrapped a pocket watch around her wrist to keep track of time. A passing watchmaker noticed this and was inspired to create the first wristwatch. Another hypothesis claims that the ancestor of the wristwatch was a timepiece gifted to Queen Elizabeth I by the Earl of Leicester, which was a round watch set in a diamond-studded bracelet on New Year’s Day 1572.

In the 16th century, pocket watches were commonly used, but no one thought to create wristwatches. Eventually, wristwatches were invented, though the exact origin remains unclear. One story suggests that one sunny morning, a woman watching her child in a park in Geneva wrapped a pocket watch around her wrist to keep track of time. A passing watchmaker noticed this and was inspired to create the first wristwatch. Another hypothesis claims that the ancestor of the wristwatch was a timepiece gifted to Queen Elizabeth I by the Earl of Leicester, which was a round watch set in a diamond-studded bracelet on New Year’s Day 1572.

The advent of the wristwatch did not garner much attention until 1806 when Queen Joséphine de Beauharnais gifted her daughter-in-law, the Princess of Bavaria, two pearl and emerald-studded bracelets, one of which featured a very small watch. Both pieces were crafted by the jeweler Nitot in Paris.

Although wristwatches were created, many still preferred pocket watches, as they served both as jewelry and a symbol of wealth. It wasn’t until 1880 that the German Navy recognized the utility of wristwatches for officers. They ordered a batch of wristwatches, making the German naval officers the first to wear this style. These early wristwatches were made of gold, featured large faces, thick hands, and had metal bands.

Following the German Navy’s orders, watch manufacturers began to consider marketing wristwatches commercially. These commercial models were made of gold, adorned with jewels, and were slightly smaller than those worn by naval officers. Soon, women’s wristwatches also featured intricate designs. However, despite being a new product, wristwatches were not widely popular, and the manufacturer Girard had to export them to Chile. Unfortunately, the situation in Chile was even worse, as people were indifferent to time; those who owned watches found them inconvenient for work. As a result, wristwatches were exported to North America, where they faced a similar lack of interest.

It wasn’t until 1902 that, despite the lack of demand, Mr. Wilsdorf, a Swiss watchmaker, continued exporting wristwatches to England, recognizing their potential. However, the situation did not improve, as people in England believed that watches could be damaged due to the normal movements of the arm.

Wristwatches continued to have a bleak fate until 1927 when a coincidence drew public attention to them. A young typist named Mercédès Gleitze intended to swim across the English Channel and succeeded on October 7, 1927. Ms. Gleitze’s achievement was not unprecedented, as many women had crossed the channel before her. However, those welcoming her onshore were amazed to see her wearing a wristwatch, assuming she had forgotten to remove it before entering the water. They thought the watch would be ruined by seawater.

Wristwatches continued to have a bleak fate until 1927 when a coincidence drew public attention to them. A young typist named Mercédès Gleitze intended to swim across the English Channel and succeeded on October 7, 1927. Ms. Gleitze’s achievement was not unprecedented, as many women had crossed the channel before her. However, those welcoming her onshore were amazed to see her wearing a wristwatch, assuming she had forgotten to remove it before entering the water. They thought the watch would be ruined by seawater.

When asked about the wristwatch, Ms. Gleitze laughed. She informed everyone that it was waterproof and that she used it to keep track of time while swimming. The following day, the Daily Mail published an article covering this unusual story, highlighting Ms. Gleitze’s special wristwatch. This unprecedented news captured public interest, particularly among the British, who are known for their love of sports. Consequently, demand for wristwatches surged, with people eager to use them for activities like badminton, horse racing, and fishing. From then on, wearing wristwatches became a trend. The number of wristwatch users grew, leading to record success by 1937. Watchmaking technology advanced rapidly, evolving from non-waterproof to models resistant to magnetism and shock, including automatic winding types.

In the United States, the first large clock was created for New York City in 1716, and in 1753, another clock was installed in Independence Hall in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. After the American Revolution (1775-1783), clock production increased significantly. In the 1800s, Simon Willard from Roxbury, Massachusetts, and Eli Terry from Connecticut patented two special types of clocks (known as the banjo clock and pillar-and-scroll clock). During this period, Seth Thomas established the Seth Thomas Clock Company in Thomaston, Connecticut, which eventually became one of the largest clock manufacturers in the world by the mid-20th century.

In the 1920s, electric clocks, which used alternating current, were introduced. At that time, these electric clocks could be off by a few seconds per day, making them suitable only for indoor use. In contrast, in physics laboratories and observatories, time needed to be measured to the thousandth or even billionth of a second. Thus, in 1929, scientists applied the vibrations of quartz crystals to clock-making. Thanks to quartz, these new clocks (quartz-based clocks) could be accurate to within two-thousandths of a second per year.

In 1948, the National Bureau of Standards in the U.S. successfully developed the atomic clock using ammonia atom vibrations at a frequency of 23,870 megacycles. The accuracy of this clock reached one part in 100 million.

Later, in 1955, Dr. Charles H. Townes from Columbia University in the U.S. developed a clock known as the ammonia maser. This clock could only be off by 1 second in 200 years. At the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), Dr. Jerrold R. Zacharias succeeded in creating a cesium atomic clock. Dr. Zacharias calculated that if this clock had been running since the time of Christ, it would be fast or slow by only ½ a second.

Due to advancements in technology, scientists believe that the most significant application of atomic clocks is the establishment of a time standard that is completely independent of the movements of the Earth and the stars.

Phạm Văn Tuấn

———————————

Back: “Sundials“

Back: “Water Clocks“

Back: “Hourglass and Candle Clocks“