Stephen Hawking did not conquer his illness, but it did not defeat him either. The young, disillusioned student suddenly discovered that life was worth living.

|

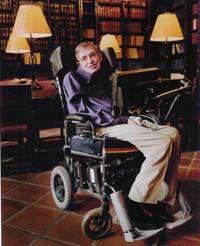

Stephen Hawking |

On the occasion of the release of the simplified version of A Brief History of Time titled A Shorter History of Time (translated into 33 languages, soon to be released by Youth Publishing House), the author—world-renowned astrophysicist Stephen Hawking—agreed to meet with a group of reporters from the popular science magazine Science et Vie (France) in Cambridge. Below is the article about that meeting and the interview.

If popularity is measured by the frequency of appearance on the Internet, then Stephen Hawking ranks very high. Just typing “Stephen Hawking” into Google will instantly yield 1,670,000 results, surpassing even Zinedine Zidane (1,010,000) or Lady Di (540,000).

We were fortunate to have the opportunity to meet the world’s most famous astrophysicist. This took place in August of last year.

The meeting was arranged by Judith Croasdell, Stephen Hawking’s assistant for the past two years, at 3:30 PM local time. She is a tough woman, in her fifties, with an authoritative voice but also showing a kind heart. She immediately warned us: “Stephen only gives interviews in dribs and drabs. He is currently extremely busy and has very little time, so he can only spare you one hour.”

An Extraordinary Man

|

The extraordinary Stephen Hawking in his high-tech wheelchair |

A few days earlier, in Paris, we met Christophe Galfard, one of Hawking’s six research students. He has been studying black holes at Cambridge for five years. He advised us to prepare questions that he could answer with a simple yes or no.

From what we knew about him, it meant we were about to meet an extremely remarkable person. A resilient individual who seems to fear nothing at all. First and foremost, he is not afraid of living. And with death, he is probably even less afraid.

When doctors diagnosed him with a neurological disease, they believed he would be lucky to live a few more years. That was in 1963. At that time, he was only 21 years old, and although he boasted that he only worked one hour a day, his academic achievements in natural sciences at Oxford University were exceptionally outstanding, where his father also studied biology and medicine.

In 1993, in his book Black Holes and Baby Universes, he recounted that since the age of 13, he knew what he wanted to do: “Physics and astronomy will provide hope to understand where we come from and why we are here. I want to explore the depths of the universe.”

Stephen Hawking did not conquer his illness, but it did not defeat him. The young, disillusioned student suddenly discovered that life was indeed worth living.

Today, at 65 years old, he has three children (Robert, Lucy, and Tim) and one granddaughter. Hawking divorced Jane and married his second wife, Elaine Mason, one of his nurses. He has been a guest of many great figures around the world.

The disease has imprisoned him in immobility and silence. He freed himself by escaping into his childhood dreams. In his book The Universe in a Nutshell published in 2001, he borrowed Hamlet’s declaration – the prince indignant at the mundanity of the world around him: “Though I be shackled in a nutshell, I consider myself the king of infinite space.”

From his journey to discover the true nature of the universe, Hawking has found jewels. For example, according to Einstein’s general theory of relativity, there must be singularities, that is, black holes, where gravitational forces distort space-time to the extent that it becomes undefined (1970). Or that black holes are not entirely black; they still emit very weak radiation known as Hawking radiation (1974). Just like in his fierce battle with illness, he has found extraordinary strength to continue living and reasoning.

A Cosmological Model That Touches Poetry

|

| Cover of A Brief History of Time |

Born on January 8, exactly three centuries after Galileo’s death, he was appointed Lucasian Professor of Mathematics at the University of Cambridge in 1970 (a position established by the Reverend Henry Lucas at this university in 1663), a prestigious post once held by Newton… 3 centuries earlier.

Like many other physicists, Hawking sought a theory of everything that could unify Einstein’s theory of gravity with quantum physics. But what he cherished most was proving that the universe emerged from nothing, spontaneously, without the intervention of any “creator,” not even requiring any specific initial conditions.

According to Galfard, his French research student: “People often assume that God has taken away the question of ‘why,’ but Stephen wants to answer that question. His physical approach is philosophical.” His most compelling intention was to reach a model of the universe “without boundaries,” which he developed in the 1980s—a model that has touched upon poetry. His fervent fans do not hesitate to compare him to Einstein.

And the Meeting

Finally, we were allowed into his room. Apart from a peculiar air purifier, the large, bright room was not much different from other scientists’ offices.

On the wall hung a blackboard filled with equations. On the bookshelf were photos of his children, a copy of Newton’s Principia, works by Carl Sagan, and translations in various languages of A Brief History of Time and other physics books. The walls were adorned with portraits of Einstein, Newton, famous filmmakers like Simpson and Steven Spielberg, and notably, a large photo of the famous actress Marilyn Monroe.

| |

Moments Beyond the Galaxies Stephen was dressed in black pants, black shoes, a gray vest, and a plaid shirt. He sat motionless in a high-tech wheelchair, his head tilted to one side, looking at us with deep blue eyes that seemed almost transparent. “Hello,” a metallic voice responded immediately to our greeting from the speech synthesizer. Judith invited us to sit beside Stephen and began the interview. “Our readers often ask two questions: What is outside the universe, and what existed before the Big Bang? We always give the same answer: nothing at all. This has made them extremely disappointed. Do you have a better answer for them?” A strange smile suddenly appeared on Stephen’s face. Or rather, the slight movement of his upper lip, one of the few gestures his body still wanted to follow. Did this question make him happy or did he find it amusing? He had certainly pondered it deeply and knew that a satisfactory answer was currently unattainable. But he would respond with the price of extraordinary efforts. With infinite patience, in the stillness and coldness of the room, he stared intently at a letter on the screen and blinked. Beep. The device focused on his glasses and understood that he wanted to talk about the letter “i.” Beep… beep… A series of words starting with “i” appeared on the screen. Another blink to select the line with the correct word. And the word “In” appeared on the screen. Minutes passed, only the steady beeping sound could be heard. Sitting there felt like a dream. All of us sat motionless, straining ourselves in efforts that were no less than his, staring at him: his skin was smooth and strangely shiny, the hole in his throat, a remnant of a tracheotomy performed in 1985, had robbed him of his voice. Judith leaned behind him to record every word, which she would later type up and send to us. Occasionally, the nurse would come in to wipe Stephen’s mouth and lift his head. Time seemed to stop. And finally, after half an hour, the answer emerged when his eyes suddenly focused on us and a metallic voice shattered the silence: “In some modern theories, the universe exists on a surface in a space with more dimensions. I believe that asking what happened before the Big Bang is no different from asking what is north of the North Pole. Simply because it is undefined.” Was that it? All of us were about to say. The answer seemed too brief. Perhaps we had expected too much. Stephen Hawking was not a prophet. And the interview continued in this manner for three hours… Pham Van Thieu

Leave a Reply |