Including the time she served as regent and as pharaoh (king of Egypt), Hatshepsut ruled Egypt for a total of 21 years.

The Legacy of a Woman Pharaoh

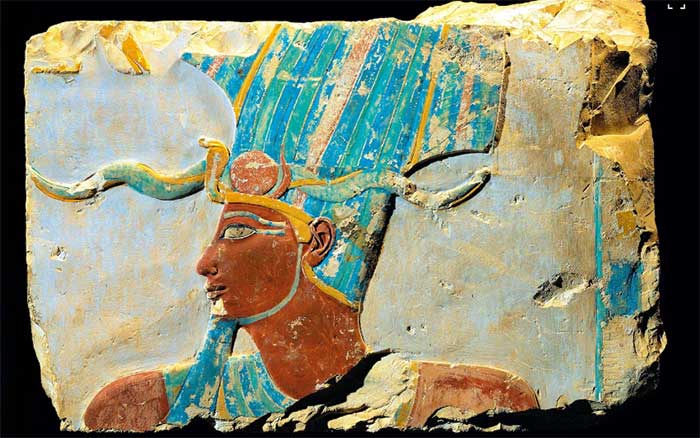

Hatshepsut depicted as a sphinx with a lion’s head. She wears the traditional masculine symbol of the lion’s mane and the false beard of the pharaoh – a sign of royalty. (Photo: National Geographic)

According to National Geographic, Hatshepsut is one of the few women in ancient Egyptian history to hold power for such a long time. She ruled during one of the golden ages of ancient Egypt, a period of great prosperity. Hatshepsut commissioned grand structures throughout Egypt: countless temples, four massive obelisks at the Temple of Amun in Karnak, along with numerous artworks celebrating her achievements.

Hatshepsut was born around 1507 BC, the daughter of Thutmose I and his royal wife, Queen Ahmose. Later, Hatshepsut married Thutmose II, her half-brother and heir to the throne, becoming his great royal wife.

Thutmose II died young, leaving behind a young son from a lesser wife who was the rightful heir. Thutmose III was too young to rule Egypt, so Hatshepsut, both his aunt and stepmother, acted as regent in his place.

Image of Thutmose III depicted in a colored relief at Deir el Bahri. (Photo: National Geographic).

Hatshepsut gradually transitioned from the role of queen regent to fully-fledged Pharaoh. As Thutmose III grew older, he had secondary authority after her and could only rule Egypt as Pharaoh after her death around 1458 BC.

Hatshepsut was likely aware of her precarious position as a woman and because she ascended to the throne in an unusual manner. Therefore, she did what wise leaders often do in times of crisis: she recreated herself. The most evident form was her depiction as a male Pharaoh. The reasons behind this are not entirely clear, but experts suggest it was due to her co-regency with a male, a situation no woman had faced before.

However, she did not pretend to be a man nor did she wear masculine attire. The inscriptions on Hatshepsut’s statues almost always contain some indication of her true gender, such as the phrases “Daughter of Re” or feminine terms.

Hatshepsut also took a new name, Maatkare, meaning the soul (ka) of the sun god (Re). The key term in this name is maat—an Ancient Egyptian expression of order and justice established by the gods. Maintaining maat to ensure the prosperity and stability of the land required a legitimate Pharaoh who could communicate directly with the gods. This was a task reserved for Pharaohs. By calling herself Maatkare, Hatshepsut may have reassured her people that they had a legitimate ruler on the throne.

It can be said that Hatshepsut was one of the most influential and powerful Pharaohs of the 18th Dynasty of Egypt. However, she faced countless discrimination and biases during her reign simply because she was a woman ruling at a time when patriarchy was the dominant norm. Thus, she had to overcome many prejudices against women in power.

Despite many obstacles, Hatshepsut changed societal standards for women in ancient Egyptian society. She demonstrated that women could be independent leaders and capable of accomplishing great things.

One of the most notable achievements during Hatshepsut’s reign was the trade missions to Punt, a kingdom near the Sahara close to Egypt. On this expedition, Hatshepsut directly contacted the leader of Punt and brought back many goods such as gold, ebony, and ivory. This mission was particularly significant for her reign as it showed the Egyptian people that a woman could be independent, resourceful, and self-sufficient. She was able to organize the entire journey and even negotiate with a highly respected leader in the Sahara region. Because she was treated equally by this leader, the Egyptian people viewed Hatshepsut as a respected and trustworthy Pharaoh.

Hatshepsut also commanded several military campaigns, including one in Nubia and another in the Levant. She expanded Egypt’s control and trade in these regions while bringing back valuable resources such as timber and precious metals.

The military campaigns in Nubia aimed to secure precious resources such as gold, ivory, and myrrh while protecting Egypt from potential invasions from the South.

Not only was she a successful ruler, but Hatshepsut was also a patron of the arts and architecture. She commissioned numerous grand structures, such as the Temple of Amun at Deir el-Bahri, the Temple of Anubis at Wadi el-Shatt el-Rigga…

She also renovated and expanded many existing architectural projects, including the Karnak Temple and the Luxor Temple.

The Temple of Millions of Years

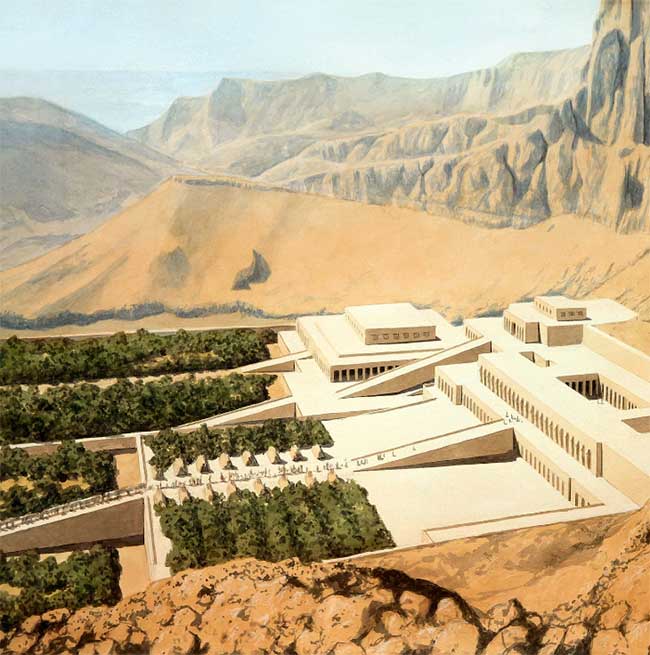

Photo of the Temple of Hatshepsut in 1955. (Photo: National Geographic).

During the New Kingdom period of Egypt (also known as the Egyptian Empire, spanning from the mid-16th century BC to the 11th century BC), Hatshepsut was one of the first Pharaohs to build the Temple of Millions of Years on the West Bank of the Nile, opposite the city of Thebes (modern-day Luxor).

Five centuries earlier, during the Middle Kingdom of Egypt (around 2050 BC to 1700 BC), Pharaoh Mentuhotep II constructed the first mortuary temple at this site. Perhaps inspired by Mentuhotep, Hatshepsut built this massive complex at the foot of a cliff, a location now known as Deir el Bahri. This sacred site was dedicated to the goddess Hathor, the protector of the dead and an important funerary deity in Thebes.

In these temples, Pharaohs would be worshiped after their death. Meanwhile, their mummies were laid to rest elsewhere, buried in separate chambers underground in the Valley of the Kings. Not only used for royal funerals, the Temple of Millions of Years also served as the focal point for other rituals: some related to the royal family, others related to the gods. Among all mortuary temples, Hatshepsut’s temple later became the architectural centerpiece of the Theban area.

The construction of the Temple of Millions of Years (or Hatshepsut’s temple) spanned approximately 15 years, overseen by Senenmut, a high-ranking official trusted by Hatshepsut. This magnificent building featured terraces and courtyards similar to the nearby Mentuhotep temple, but Senenmut implemented several enhancements to create an unparalleled structure. The building was named Djeser-Djeseru, meaning “the holy of holies.”

The Hatshepsut Temple is arranged around a central sloped area. Along this slope at varying heights are three expansive courtyards.

Illustration of the Hatshepsut Temple at its glorious peak. (Photo: National Geographic).

Today, the walls and courtyards of the Hatshepsut Temple may seem somewhat monotonous, but in her time, they were filled with vibrant colors, surrounded by lush gardens and pools, and lavishly decorated with sculptures and reliefs. Each decorative element conveyed a religious or political message appropriate to the ceremonial purpose of the building.

The layout of the Hatshepsut Temple was meticulously designed. Most notably, the temple’s location aligned perfectly with the Temple of Amun at Karnak, across the Nile. Additionally, the precise east-west orientation of the slope mimicked the daily journey of the Sun, or, according to the beliefs of that time, the path of the god Re.

The temple also harmonized with the Valley of the Kings located to the West. This royal cemetery was inaugurated by Hatshepsut’s father, Thutmose I. In fact, the tomb KV20—where Hatshepsut and Thutmose I were buried—lies in a straight line from the sanctuary of Amun, the innermost room of the Hatshepsut Temple. Some experts suggest that the original plan was to connect KV20 with the Amun sanctuary through a tunnel through the interspersed cliffs, but poor stone quality prevented this from being executed.

The stone balustrades on either side of the central slope are guarded by massive stone lions. A row of columns separates the first courtyard from the second. Surrounding the second courtyard are the famous reliefs depicting a trading expedition that Hatshepsut sent to the Land of Punt.

The magnificent reliefs carved on the portico of the second courtyard of the temple at Deir el-Bahari depict various scenes, including Hatshepsut’s expedition to Punt during her eighth and ninth regnal years. These reliefs provide a glimpse into the terrain, wildlife, flora, and inhabitants of this mysterious land.

The expedition to Punt was carried out along the shores of the Red Sea. The Egyptians loaded the ships with goods such as ivory, cinnamon, myrrh, cosmetics, and animal skins. They also brought back myrrh trees, which were planted in the complex of Hatshepsut’s temple. The reliefs on the gateway illustrate these myrrh trees and depict Hatshepsut presenting offerings from Punt to the god Amun.

Other reliefs portray the divine birth of Hatshepsut, who was believed to be the daughter of the god Amun-Re and Ahmose, the wife of Thutmose I. The divine origin of Hatshepsut was a crucial tool in legitimizing her rule over Egypt.

The second courtyard also features two sanctuaries: one dedicated to the goddess Hathor and the other to the god Anubis.

Twenty-four colossal statues line both sides of the entrance to the third courtyard. These statues depict Pharaoh Hatshepsut in the guise of Osiris, the god of the afterlife. She wears a false beard and the double crown of Upper and Lower Egypt while holding symbols of royalty.

Hatshepsut constructed several sacred spaces in her temple at Deir el-Bahari, the most famous of which is the sanctuary honoring Hathor, one of the oldest goddesses in Egypt.

After her death, Hatshepsut was intentionally forgotten by Thutmose III, who ordered the destruction of all statues, monuments, and imagery of her, including depictions of her temple. Her images were chiseled away from monuments, and her statues and works were destroyed.

However, after a significant reconstruction in the 20th century, Hatshepsut’s grand temple at Deir el-Bahari (Arabic for “Northern Monastery”) still stands today, nestled beneath the red rocks of a cliff. The beauty of this architectural wonder has captivated the ancient world and serves as a testament to Hatshepsut’s glory and her devotion to the gods.