Researchers Discover an Ancient Reptile with a Neck Three Times the Length of Its Body and Sharp Teeth for Ambushing Prey.

The fossil named Tanystropheus was first described in 1852 and has puzzled scientists ever since. At one point, paleontologists believed it to be a winged lizard similar to the pterodactyl, with its long hollow bones thought to be digits at the wing’s tips. Later, they realized these were actually elongated neck vertebrae. Tanystropheus was a 6-meter-long reptile with a 3-meter-long neck, three times the length of its body.

Reconstruction of Tanystropheus. (Image: CNN).

Previously, researchers were unclear whether the creature lived on land or in water, and they were uncertain if a smaller specimen was an immature Tanystropheus or a completely different species. Through CT scanning of fragmented fossil skulls and digital reconstruction, the research team found evidence that Tanystropheus lived in water. Examining growth rings in the bones, they concluded that the larger and smaller specimens belonged to two separate species living in close proximity but not competing for food, as they hunted different prey. The findings were detailed by Olivier Rieppel, a paleontologist at the Field Museum in Chicago, and his colleagues in the journal Current Biology.

Tanystropheus lived approximately 242 million years ago, during the Middle Triassic period. According to Rieppel, Tanystropheus resembled a stout, short crocodile with an extraordinarily long neck. The larger specimen measured 6 meters long with a 3-meter neck, yet it had only 13 cervical vertebrae. Its neck was not very flexible, supported by bones known as cervical ribs. In Switzerland, where many large Tanystropheus fossils have been excavated, researchers also found fossils of similar creatures that were only about one meter long. They are still uncertain whether Tanystropheus lived on land or in the sea, and whether the smaller specimen was an immature individual or a different species.

To solve these two mysteries, the research team employed new technologies to examine fossilized bones in detail. The skull of the Tanystropheus fossil was broken, but Stephan Spiekman, a scientist at the University of Zurich and the lead researcher, was able to use CT scans to create a 3D image of the internal bone fragments. “The power of CT technology allows us to examine details that cannot be observed in fossils,” Spiekman said. “From a shattered skull, we could reconstruct a nearly intact 3D skull, revealing important morphological details.”

The fossil skull has several important characteristics, including a nostril located at the top of the snout similar to that of a crocodile, indicating that Tanystropheus lived in water. It could lie in ambush, waiting for fish and squid to swim by, then snap them up with its long, sharp teeth. This creature could crawl onto land to lay eggs but primarily lived in the sea.

To determine whether the smaller specimen was an immature individual or a distinct species, the research team examined growth patterns and age in the bones. They found that the smaller fossil belonged to an adult animal, revealing that there are two species of Tanystropheus. They named the larger species Tanystropheus hydroides after a long-necked monster from Greek mythology. The smaller species was named Tanystropheus longobardicus.

Differences in size and tooth shape between the two Tanystropheus species suggest they may not have competed for prey. According to Spiekman, the two closely related species evolved to exploit different food sources within the same environment. The smaller species likely fed on shellfish such as shrimp.

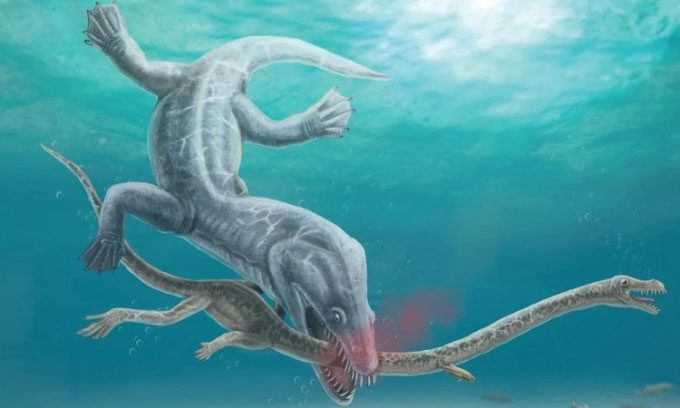

Simulation of Tanystropheus hydroides being bitten by a larger predator. (Image: Roc Olivé)

In a study published on June 19 in the journal Current Biology, the research team found evidence of an attack occurring from above. A predator descended and bit off the neck of Tanystropheus. There were no traces of the body, but the remaining head and neck were well-preserved. Scientists speculate that the predator targeted the long neck to quickly kill Tanystropheus and consume its meaty body.

By measuring the distance between bite marks, the research team was able to compare the size of the bites with those of large predators that lived in the area at the time. The final list included Cymbospondylus buchseri, a lizardfish that could grow up to 5.5 meters long, and Nothosaurus giganteus, a giant reptile measuring 7 meters. A third possibility is Helveticosaurus zollingeri, a 3.6-meter predator with strong forelimbs, a flexible tail, and a mouth full of sharp teeth.