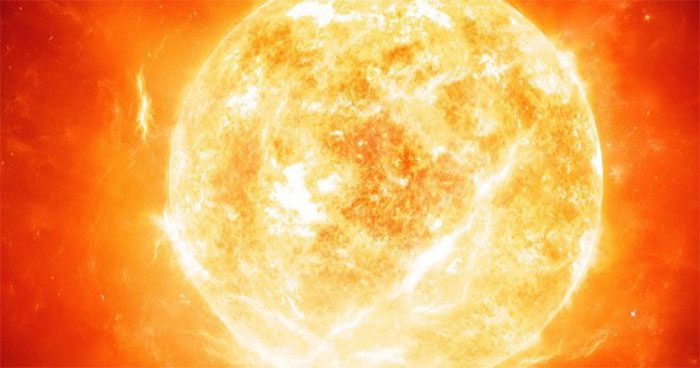

When we reach the surface of the Sun, we will find it incredibly hot, with a surface temperature of 5,700 degrees Celsius and blindingly bright light.

If we look a little closer, we may see numerous bubbles, resembling a pot of boiling water. Some of these bubbles appear darker than others. The darker bubbles are slightly cooler than the lighter ones, but every centimeter of the Sun’s surface is still extremely scorching.

From One Region to Another

We continue our journey, diving through one of the giant bubbles on the surface and heading towards our first stop, the convective zone.

At this moment, we are surrounded by a hot fluid environment known as plasma, filled with bubbles created by the continuous movement of hot gases rising and cool gases sinking. These bubbles are always in motion, expanding and contracting, and some even burst as our spacecraft shakes and moves deeper towards the Sun’s core, like a ship on the open sea.

After traveling about 200,000 km (equivalent to 15 times the Earth’s diameter), the spacecraft stops shaking. We arrive at our second stop, the radiative zone.

This region of the Sun is extremely hot. At this point, the temperature outside our spacecraft is 2 million degrees Celsius. If we could see each particle of light, known as photons, we would see them bouncing between tiny particles called atoms, forming plasma.

These particles bounce back and forth, creating a dance that scientists call “random walk”. A single photon can take hundreds of thousands of years to randomly walk through the entire radiative zone.

Our spacecraft will accelerate to get through this region more quickly.

The mass of all the plasma above presses down, meaning that the plasma around us is denser than gold, and the temperature rises dramatically to 15 million degrees Celsius. We are nearing the end of our journey, which is the core of the Sun.

Welcome to the Core

Before we penetrate the core, we must shrink down to the size of an atom. This is the only way we can see what happens here, as what we are about to witness are atoms, which are millions of times smaller than a grain of sand.

The core of the Sun is home to billions of billions of hydrogen atoms, the lightest element in the universe. The immense pressure and heat force these atoms close together, allowing them to combine and form heavier atoms.

This phenomenon is known as nuclear fusion. Hydrogen atoms combine to create a completely new substance called helium.

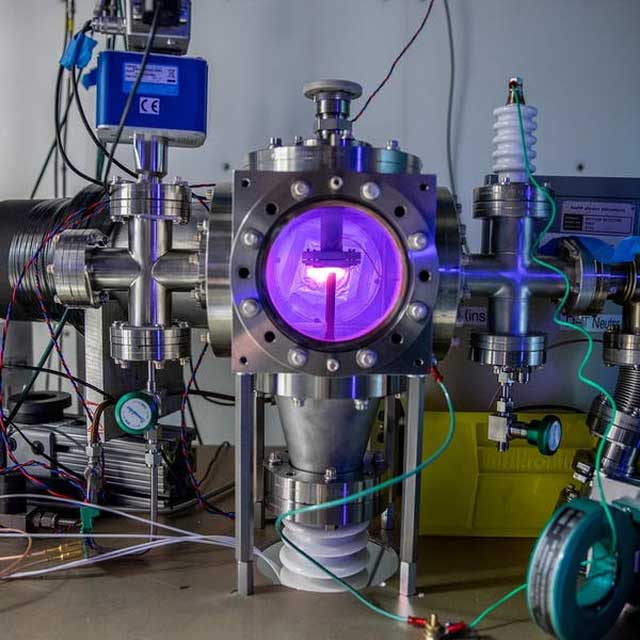

So, at this moment, we are in the core of the Sun. What does it really look like? Here, everything is not just blindingly bright to the point of being unseeable but also transforms into a beautiful pink hue.

A hydrogen plasma experiment at the Berkeley National Laboratory, USA, shimmering in pink.

We cannot be sure what the Sun’s core looks like to the naked eye, but we can see hydrogen plasma appearing pink in laboratories on Earth. Therefore, we can reasonably hypothesize that the hydrogen plasma in the Sun’s core is also pink.

When atoms combine, they release a significant amount of energy in the form of light. This light escapes from the core to the radiative zone and bounces around in this zone until it eventually moves to the convective zone. After that, the light continues towards the surface through plasma bubbles, and from the Sun’s surface, it travels ceaselessly throughout the universe.

Now it is time to leave the hottest place in the Solar System and return to Earth. Our recent journey took us 700,000 km deep into the Sun, passing through the bubbles of the convective zone, through billions of rays of light in the radiative zone, and into the mysterious nuclear fusion core.

Upon returning to Earth and looking up at the Sun, we see as if we are looking into the past. Today, we know that the light we are seeing was generated hundreds of thousands of years ago in the hottest part of the Solar System.