Applying 2 – 3 volts of electricity will release dissolved minerals from seawater to bond wet sand into a solid structure similar to rock.

Sea level rise is one of the greatest threats posed by global warming due to human activities. However, the prospect of cities and farmland being permanently submerged beneath ocean waves may still be far off. In the meantime, a more pressing issue is rising tides causing erosion that leads to coastal retreat, exposing homes and critical infrastructure.

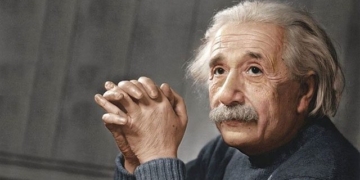

Electric stimulation will release dissolved minerals from seawater to bond wet sand into a solid structure. (Photo: Northwestern University).

Traditional methods to combat this, such as tidal barriers, are very costly and can have side effects, but natural barriers are often much more effective. To address this, Dr. Alessandro Rotta Loria at Northwestern University studied how bivalve species, such as clams and mussels, withstand waves. They dissolve minerals from seawater to create shells, inspiring Rotta Loria and colleagues to find ways to bond sand particles to create a sturdier structure, as reported by IFL Science on August 22.

These mollusks rely on the energy released from their food to do this, but Rotta Loria found that electric currents can achieve similar results. Moderate electrical stimulation can release dissolved minerals from seawater to bond wet sand into a solid structure resembling rock.

It only takes 2 – 3 volts of electricity to trigger the desired chemical reactions in seawater, producing calcium carbonate – the main component of hard corals, shells, and limestone. Increasing the voltage slightly will produce magnesium hydroxide and hydromagnesite, components of tufa and travertine. With sand, these molecules act like mortar between bricks. The research team found that this method is effective with the common iron sand around volcanoes as well as the more prevalent silica beaches.

“After treatment, the sand looks like rock. It is solid instead of granular and non-sticky. The minerals themselves are also much more durable than concrete, so the resulting sand structure can become as firm and hard as sea walls,” said Rotta Loria.

The bonding of sand occurs instantaneously, but for long-lasting effects, the research team found that it is necessary to maintain the voltage for several days. This process can even be reversed if the threat subsides and residents wish to restore sandy beaches.

The new research was published in the journal Communications Earth and Environment and has yet to be verified outside the laboratory. However, the research team estimates that it will only cost $3 – $6 for each cubic meter of sand wall produced. Current coastal protection methods are up to 20 times more expensive.