Thai scientists have begun producing hydrogen plasma with the support of a tokamak device likened to an “Artificial Sun” donated by China last year.

The research team stated that they are confident the device named Thailand Tokamak-1 (TT-1) will reach full power this month, paving the way for increased temperatures inside the machine, as reported by the South China Morning Post on May 11. The tokamak, a donut-shaped device designed to harness thermonuclear energy, generates extremely strong magnetic fields to contain and control hydrogen gas heated to ten times the core temperature of the Sun. Thermonuclear reactions, similar to the process that has kept the Sun active for the last five billion years, are considered the ideal solution for humanity’s future energy needs. Unlike current nuclear power plants that use uranium, thermonuclear reactors do not produce radioactive waste.

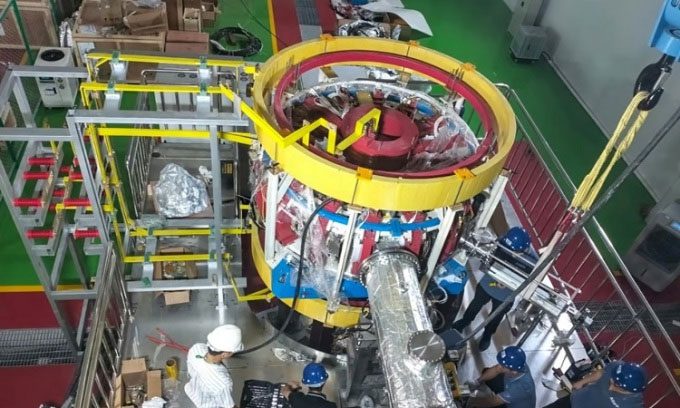

The tokamak device donated by China to Thailand. (Image: SCMP)

The refurbished device was developed and donated by the Institute of Plasma Physics (ASIPP) under the Chinese Academy of Sciences in Hefei, Anhui Province. TT-1 is expected to help train scientists and engineers from Thailand and other Asian countries. Last year, the Thai research team, along with their Chinese colleagues, began testing the device after it was installed. The first successful test took place on April 21, according to Nopporn Poolyarat, head of the Thermonuclear and Plasma Department at the Thai Nuclear Technology Institute.

Thermonuclear energy is generated from nuclear fusion reactions, which occur at extremely high temperatures. In these reactions, two atomic nuclei, in this case, isotopes of hydrogen, deuterium and tritium, fuse together to form a heavier nucleus and release enormous amounts of energy. Nuclear fusion occurs in a state of matter known as plasma, a superheated ionized gas. The term “breakdown” refers to the transition from an insulating gas to a conductive plasma. The current produced in the first plasma experiment was at 2,000 amperes, significantly lower than the achievements made by Chinese researchers.

Nopporn was one of nine team members who spent three months in Hefei last year learning how to operate the tokamak. After the first trial, he and his colleagues sought to make incremental improvements. They managed to heat the plasma to levels of 60,000 – 70,000 amperes for a duration of 0.05 seconds. The current key focus is to increase the plasma temperature to a maximum of 100,000 amperes within 0.1 seconds by mid-May.

After the Chinese engineering team finally departs Thailand at the end of this month, they will maintain contact to support the operation and maintenance of the device. The Thai researchers are also working closely with the country’s largest power producer, the Electricity Generating Authority (EGAT), which is involved in training, installation, and operation of the machine. According to Nopporn, they plan to upgrade the machine, including the use of artificial intelligence to ensure smooth operation.

Nopporn and his colleagues will study how to increase the plasma temperature using a physical phenomenon known as “transport barrier”. “Inside the tokamak, it is really hot, and heat is lost to the outside. But if we can activate that barrier, the heat can be retained, and we can maintain very high temperatures within the reactor,” the researcher explained.