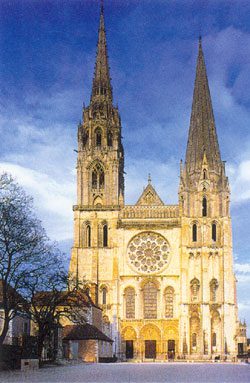

The west facade of Chartres Cathedral features an eclectic mix of styles. The tower construction began in the 1130s and 1140s, with an additional spire added nearly 400 years later on the left. The rose window is designed in the Gothic style, dating around 1210. Construction Period: 1194 – mid 13th century

- Location: Chartres, France

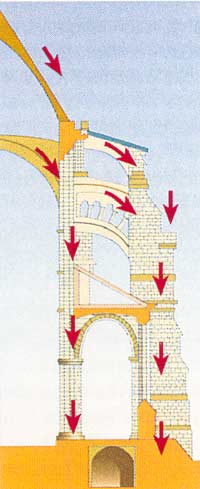

Chartres Cathedral is one of the best-preserved Gothic cathedrals in the Île-de-France region, just outside Paris, representing a significant development in Gothic architecture across Europe. Other notable cathedrals from this era include St. Denis and Sens in the 1140s, followed by Laon and Paris in the 1160s, Bourges and Chartres in the 1190s; Reims and Le Mans in the 1210s, and Amiens and Beauvais in the 1220s and 1240s. Each of these cathedrals is unique, but together they create a lasting pattern that has influenced Christian architecture for centuries. Essentially, this pattern relies not on the strength of solid masonry but on a balanced system of forces. The pointed arch replaces the varying-width arch while maintaining equal height, concentrating the weight of the stone vault at specific points rather than distributing it along the walls. This allows for larger openings in the walls, resulting in expansive windows and distributing lateral forces down to the ground through the buttressing system, giving the entire structure an ethereal feel and dynamic lines previously unattainable.

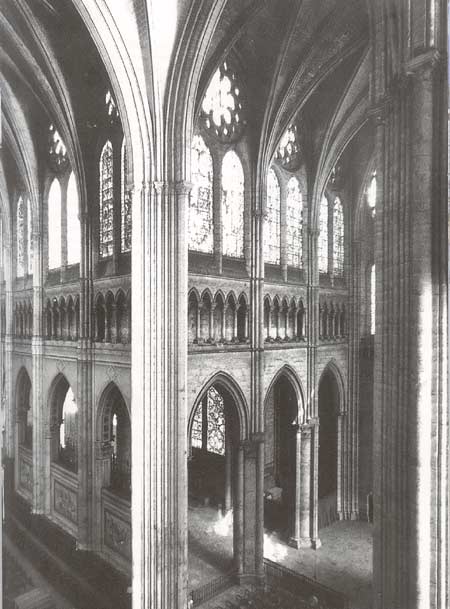

Chartres follows the traditional Latin cross layout, with a nave and choir positioned at the crossing. The choir is located at the end of the semicircular apse, with chapels radiating outward. The interior rises to three levels: a series of clerestory arches supported by cylindrical columns with the shafts oriented in the four cardinal directions, and the inner columns extending to the vaulted ceiling. The narrow west façade features five small arches that project from the main structure, while the upper wall is deeply recessed with a ribbed pattern. Uniquely, the upper wall extends downward to a point beneath the arch. Of the nine towers originally planned for Chartres, only two were completed.

|

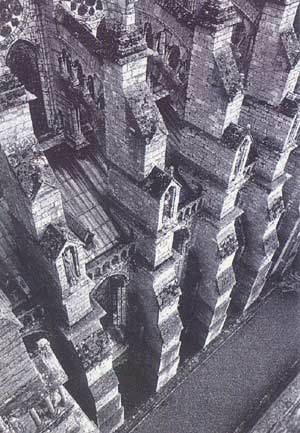

| The north side of the nave: The buttressing structure of the vault features many smaller columns that are not functionally efficient. This arch structure above was added in the 14th century. |

While Chartres is emblematic of the early Gothic period in many ways, what makes it particularly remarkable is the preservation of its sculptural integrity—and even more so, the extensive stained glass found within the cathedral. Thus, collectively, Chartres is considered one of the pinnacles of world architecture.

Construction of Chartres

The original cathedral, a massive Romanesque structure, featured a portal with three sections projecting dramatically, known as the “Portail Royal,” constructed on site in the 1140s. Fifty years later, on June 10, 1194, this cathedral was destroyed by fire, leaving only the portal intact. The remaining structure was entirely rebuilt.

It was decided to preserve the ancient Portail Royal, though this impacted the overall stylistic coherence, a decision that proved wise, as it ensured the survival of some of the most exquisite sculptures from the medieval period. Nonetheless, the overall impression at Chartres remains one of a unified design, characterized by clear choices and aesthetic decisions that must have been adhered to. This suggests the work of a singular mind, a distinct architect referred to by historians as the “master of Chartres.” However, it is compelling to note that over the span of 30 years of construction, at least nine different masters contributed, each leaving their mark through numerous details and significant decisions. Did they all follow a master plan, or did each weave their own ideas into what had been established by their predecessors? This is a fascinating question that remains difficult to answer.

Fact Sheet:

- Total Length: 155m

- Width of the West Façade: 47.5m

- Width of the Nave: 14m

- Length of the Nave: 73m

- Height of the Vault in the Nave: 37m

- Height of the North Tower: 115m

- Height of the South Tower: 107m

- Diameter of the Large Rose Windows: 13.4m

Construction Techniques

|

| The structural system applied at Chartres and all Gothic cathedrals: The weight of the vaulted roof is transferred to the ground through the buttressing system of the vault. |

Gothic cathedrals were constructed by teams of builders under the supervision of a master craftsman, often moving between projects and sometimes even across borders. The team, known as “in-house,” consisted of skilled artisans, each with their own specialties. Stone quarried had to be cut as precisely as possible to minimize the transport of complex details, such as the ribbed vault or the window tracery, which needed to be laid out on the ground according to the actual scale drawing. Ideally, the entire layout had to be marked and the foundation excavated in one go.

Construction progressed layer by layer, with the timeline of construction often recorded through the rows of masonry within the structure. In massive projects like Chartres, cracks and variations in the masonry indicate the construction process.

Typically, church construction begins at the east end, but Chartres is different: The shape of the buttressing system of the nave resembles a quarter-circle wheel with spokes, appearing older than similar structures at the eastern choir and the windows in the aisles, where the narrow windows with pointed arches are simpler than those in the nave.

Scaffolding was quite expensive, thus the common method employed was to build wooden working platforms supported by the completed walls rather than erecting scaffolding from the ground up. Once the full height of the wall was reached, the interior space was covered before constructing the vaulted roof, providing shelter for the workers. A frame was then built, and the intervening spaces were filled with minimal use of wood.

Stones were lifted to the scaffolding using earthen ramps or cranes operated by track wheels within the construction site. Decorative carving such as column capitals was done on-site, while figure sculptures were carved in workshops and installed upon completion—some medieval sculptures bear numbers indicating their installation locations. The final process involved glaziers carefully fitting stained glass into the stone tracery.

Sculpture and Glass

The architecture of Chartres appears to balance simplicity with proportion so that the viewer’s gaze is not distracted by the external sculptures or the stained glass installed within.

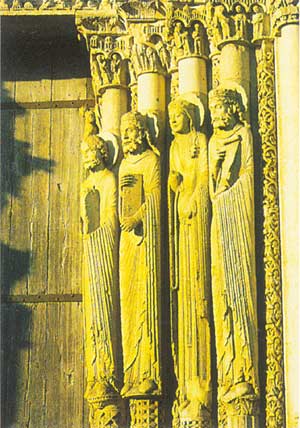

|

| The four sculptural columns at the Portail Royal, the oldest sculptures in the cathedral, depict figures from the Old Testament but cannot be definitively identified. |

The story of the sculptures begins with the Portail Royal from the 1140s. Alongside St. Denis, the Portail Royal marks independent sculptural work in the West, featuring human-shaped columns. These columns lean against or replace some columns grouped around the cathedral’s entrance, adorned with numerous high-relief sculptures on the lintels and architectural panels above.

The north and south transepts feature even more elaborate vaulting. Constructed approximately 80 years after the Portail Royal, these aisles belong to a different world, a world of humanism in the 13th century, with idealized figures that blend spiritual strength with the physical might of a hero.

However, the feature that makes Chartres Cathedral most renowned is its stained glass. The typical reaction upon entering the cathedral is one of astonishment, as it appears almost dim. Medieval glass is not brightly translucent. The dark colors resemble gemstones, and it takes time to adjust to the level of light (it must be noted: one needs binoculars to fully appreciate the details of the glass). These challenges make Chartres unlike any other cathedral.

The cathedral was adorned with stained glass in the first half of the 13th century, funded by contributions from pilgrims, noble patrons, and merchants in the city. Their professions were seen as gifts commemorated by the patron saints, linked to details found in the Bible. Most of these windows require expert guidance to fully understand their significance. The tall, pointed arches of the windows in the side aisles of the church often feature 20 to 30 different scenes. Higher up, the scale becomes even grander, with colossal deities resembling Aaron, their chests adorned with jewels and their eyes wide open, gazing downwards.

In stark contrast to the themes depicted in the windows, medieval theologians added a mystical quality to light and color, as elaborated by Abbot Suger in the construction of the Abbey Church of Saint-Denis. “Visible light, both that which is created by nature in heaven and that which is created by man on earth, is an image of intellectual light, and above all, it is an image of the true Light”.

The intersection in Chartres Cathedral, looking towards the north transept, with the choir on the left