- Construction Period: 1675 – 1711

-

Location: London, England

St. Paul’s Cathedral, designed by Christopher Wren, is the largest Baroque structure in England and would not exist without the catastrophic Great Fire of London in 1666, which destroyed the medieval church and turned much of the city into ashes. Nonetheless, the story surrounding Wren, particularly the dominant feature of his thoughts from the beginning—the dome—seems to resonate with the pre-Fire period.

|

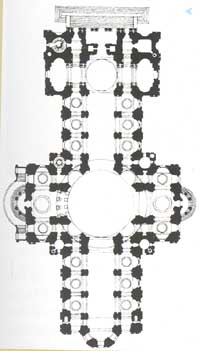

| The final layout of St. Paul’s Cathedral features a central nave and altar area according to conventions, evolving through numerous experiments and changes. Initially, Wren envisioned a central Greek cross layout with a much more prominent dome. |

In 1663, the old church, which had long raised concerns, exhibited alarming signs of instability beneath the tower at the crossing. Wren proposed demolishing the tower, constructing a larger crossing, and covering it with a dome topped with a giant pineapple-shaped finial, a proposal that was accepted.

The dome was a challenge that all architects aimed to construct, yet opportunities remained limited. Brunelleschi built the dome of the Florence Cathedral in 1420. Michelangelo’s dome at St. Peter’s Basilica followed in the late 16th century. In Paris, François Mansart’s Val-de-Grâce and Jacques Lemercier’s Sorbonne Cathedral began construction in 1665, during which Wren saw the project during his one trip abroad.

Design Development:

After the fire, all previous plans were unsuitable, forcing Wren to start anew. From that point until completion in 1711, Wren’s office was filled with a plethora of sketches and designs that should have clarified the design process but often did the opposite.

The major stages of development occurred during this period. In 1670, Wren proposed a design so modest it was difficult to comprehend, featuring a cupola and a small rectangular church. When this design was deemed insufficiently impressive, he created several based on a Latin cross layout with a cupola over the crossing and some following a Greek cross (with equal-length arms) also featuring a dome like Bramante’s original design for St. Peter’s Basilica.

Wren favored the Greek cross layout, and in 1763 he created a model, the so-called “Great Model”, which garnered approval. Ultimately, as with St. Peter’s Basilica, church officials insisted on a traditional layout with a long nave (they claimed it was “not representative of a cathedral style”). However, the Great Model remained a vivid testament to Wren’s imagination. As an architectural work, it was more interesting than the church itself: four equal-length arms plus an airy portico at the western end and a massive dome in the center. The arms connected not with straight lines but with curves, an incredibly brilliant idea, unique in England and worldwide. The curvature—where the concave lower wall met the convex curve of the dome—was a miniature embodiment of the outstanding Baroque style.

The next stage was the most troubled, a design where the confident expertise of the Great Model was replaced with what seemed to be an oddly amateurish approach. Here, Wren had to revert to a longitudinal layout, but at the crossing, he combined a dome with a four-tiered tower: an onion-shaped foundation supporting a round wall beneath the cupola through composite columns, followed by a small dome and finally a pagoda-like tower similar to the last tower he proposed for St. Bride’s Church on Fleet Street. This design received Royal Approval in May 1675, but Wren always retained the right to alter his intentions as construction progressed.

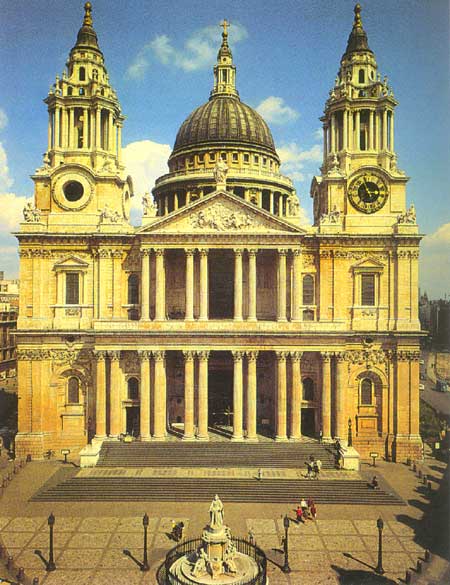

The western façade of St. Paul’s Cathedral is the final design element.

The landscape at the tympanum of St. Paul’s Cathedral was renovated by Francis Bird (1706),

an impressive yet often undervalued Baroque sculpture in England.

He did not complete this immediately, and from here on, the construction proceeded quite smoothly. The narrative of the approved design was replaced with a dome and heightened details very cautiously. The only unresolved element was the tower and western façade, which would not take shape until after 1700.

Construction of St. Paul’s Cathedral

|

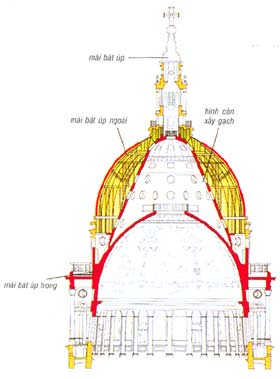

| Wren’s three dome structures: the outer dome is non-load-bearing, the invisible curved structure supports the dome, and the inner dome is visible from inside. |

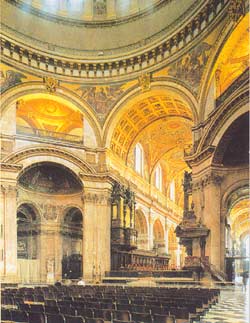

To realize his dream, Wren faced many challenges, which he solved excellently but was later criticized by 19th-century writers associating him with the principles of A.W.N. Pugin and John Ruskin, publicly accusing him of being “dishonest.” The layout included conventional elements: a nave with aisles, a transept, and an altar. The dome did not rest on the four main supporting columns where the nave, transept, and altar met, by omitting the end spans of the aisles at the corners and instead resting on eight columns. As initially intended and demonstrated in the Great Model, the arches between the eight supporting columns were supposed to be equal, but the result forced Wren to reinforce them to the point where the diagonal arches became narrower than those in the cardinal directions. To address this optical inconsistency, he introduced small semicircular windows or balconies at the diagonal beams corresponding to the main spans, continuing to extend the outline above the surface of the adjacent supporting columns. This resulted in creating the effect of a ring of eight equal arches to the eye. In reality, they were not concentric with the arched vaults when viewed from below, which was a glaring flaw.

Actual Measurements:

-

Total Length: 156m

-

Transverse Length: 76m

-

Nave Width: 37m

-

Western Façade Width with Chapels: 55m

-

Height to the Railing: 33m

-

Height to the Golden Balcony: 86m

-

Height to the Crossing at the Dome’s Peak: 110m

-

Western Tower Height: 68m

-

Area: 5480m2

According to estimates, the structural supports for the dome posed more challenges for Wren than any other structure in the cathedral. He built eight supporting columns from rubble stone (material salvaged from the old St. Paul’s Cathedral) faced with Portland stone.

|

| To maintain the impression of eight equal arches beneath the dome, Wren camouflaged the four diagonal beams to appear of the same width as the beams in the cardinal directions. |

However, soon after he realized the rubble stone was not strong enough and had to undertake a process of replacing the core with meticulously crafted solid masonry. To enhance the safety of the “Great Ring or Large Iron Chain” made by the master blacksmith Jean Tijou, who was renowned for his beautiful iron screen panels in the chancel aisles, placed around the base of the dome in 1706 to prevent spreading, with additional metal chains added the following year.

The dome itself employed another clever trick. Earlier domes, like those at the Florence Cathedral and St. Peter’s Basilica, had two layers—the inner dome visible from the outside and another dome visible from inside. Wren wanted to cover the dome with an unusually heavy cupola, adding a curved brick structure that could be seen from both inside and outside, rising from the balcony level and supporting the cupola. The inner dome was solid masonry, while the outer dome was made of wood and lead.

Finally, Wren constructed a protective wall atop the side walls, creating a two-story vertical cross-section rather than a one-story representation of the true height of the side walls. This demonstrates that the main elements (nave, transept, altar) received light from the upper windows as well as in the medieval synagogue and (in the same tradition) the curved vault was supported by thrust-bearing structures. From the inside, this effect is not noticeable, and few visitors perceive it from the outside, but indeed, it is very clear when viewed from above. This effect, as Wren intended, outwardly appears to create a solid base for the soaring dome, structurally generating additional thrust-bearing structures for the dome.

All three of these ingenious solutions were implemented, and St. Paul’s Cathedral would have been worse off without them. However, they also provided Pugin with grounds to justify his ridicule of “half the structure built to conceal the other half.”

|

| From above (the Wren landscape seems impossible to achieve), the screen wall conceals the support columns awkwardly visible |

The final section to be completed was the West façade. There is some evidence suggesting that Wren would have preferred a monumental Ionic architecture for the portico but could not find stone long enough to span the distance between the two adjacent columns. The two towers reflect the influence of Italian Baroque style, also showcasing other characteristics of St. Paul’s Cathedral, such as the horizontal end which seems to reference the Church of Santa Maria della Pace by Pietro da Cortona in Rome. This could be an evolution of Wren’s personal taste or possibly a contribution from younger members of his office. This component reflects the work of several of his design staff, some of whom were architects with their own interests.

Wren was a designer, not a builder; he assembled a large team of highly skilled professionals to carry out the construction. Over nearly 40 years of building St. Paul’s Cathedral, he employed the craftsmanship of 14 contractors. They supervised every step of the process, from the stone quarry in Portland to the final detailing on site. In the busiest year (1694), there were as many as 64 masons on site, in addition to carpenters, lead workers, stone carvers, and plasterers. Among the sculptors, the most renowned was Grinling Gibbons, along with Edward Pearce, who were responsible for the stone carvings on the exterior, where numerous charming angelic figures protrude from the brick columns and window frames, as well as the wood carvings in the choir area.

In his old age, Wren was treated poorly and was removed from his position as surveyor general. One of the council’s final decisions that went against his wishes was to place a railing around the top of the wall. Wren bitterly remarked: “Ladies think there is nothing worth seeing without a corner.”

“If you want a monument, look around you.” – Wren’s son inscribed this inside St. Paul’s Cathedral, 1723