With appendages sprouting from its head and a rigid mouth, an ancient shrimp-like creature is believed to have been a top predator of its time.

This marine creature is notoriously fearsome. Paleontologists suggest that this species was responsible for leaving scars and crushing the fossilized remains of trilobites. Trilobites were primitive, hard-shelled invertebrates that roamed the ocean floor before going extinct in mass extinctions.

Anomalocaris canadensis is one of the largest marine animals that lived 508 million years ago.

Anomalocaris canadensis, measuring 2 feet (0.6 meters) long, is one of the largest marine animals that existed 508 million years ago. This “underwater hunter” emerged in the Cambrian period, a crucial time in Earth’s history marked by a surge in biodiversity and the appearance of many large animal groups that still exist today.

Lead author Russell Bicknell, a postdoctoral researcher in the paleontology department of the American Museum of Natural History, stated: “That doesn’t add up. Trilobites have a very hard exoskeleton. Essentially, they are made of rock. Meanwhile, Anomalocaris canadensis is mostly soft and squishy.”

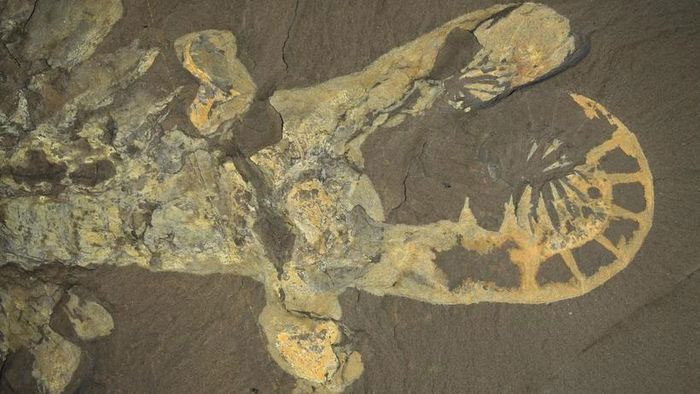

Bicknell and his collaborators from Germany, China, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom have created a new three-dimensional reconstruction of this creature. They used computer modeling to gain a better understanding of its biological mechanisms. This model is based on a well-preserved but flattened fossil found in Canada.

Previous research suggested that the mouthparts of Anomalocaris were incapable of processing hard food. Therefore, Bicknell and his colleagues focused on whether the long, spiny appendages of this creature could chew on trilobites.

The scientists used modern-day whip scorpions and whip spiders as similar subjects, as they have analogous appendages that allow them to grasp prey. The research team demonstrated that the segmented appendages of the predator could indeed grasp prey while also being able to extend and bend.

However, the team’s analysis revealed that this marine creature was weaker than initially assumed and was “unlikely” to crush hard-shelled prey. Bicknell noted that this marine creature is a hybrid between a shrimp and a cephalopod. According to the research group, this creature was more likely to dart quickly after soft prey rather than hunt hard-shelled animals on the ocean floor.

“Previous conceptions suggested that these animals were carnivorous, hunting anything they wanted. However, we are finding that the dynamics of the Cambrian food web may be much more complex than we previously thought,” Bicknell explained.