Archimedes of Syracuse was a Greek mathematician, physicist, engineer, inventor, and astronomer. Although little is known about his life, he is considered one of the leading scientists of antiquity.

The Life of Archimedes

Biography

Archimedes (284 – 212 BC) was a renowned teacher and scholar of ancient Greece, born in the city of Syracuse, a city-state in ancient Greece. His father, the famous astronomer and mathematician Phidias, personally educated and guided him deeply into these two fields. At the age of 7, he studied natural sciences, philosophy, and literature. By the age of eleven, he went to study in Egypt, where he became a student of the renowned mathematician Euclid; then he traveled to Spain and eventually settled permanently in Syracuse, Sicily. Funded by the royal family, he dedicated himself entirely to scientific research.

Archimedes made significant contributions in the fields of Physics, Mathematics, and Astronomy.

- In Physics, he invented a pumping machine to irrigate the fields of Egypt, was the first to use levers and pulleys to lift heavy objects, and discovered the principle of buoyancy.

- In Mathematics, Archimedes solved the problem of calculating the length of curves and spirals, and notably calculated Pi by measuring figures with many inscribed and circumscribed angles.

- In Astronomy, he studied the movements of the Moon and stars.

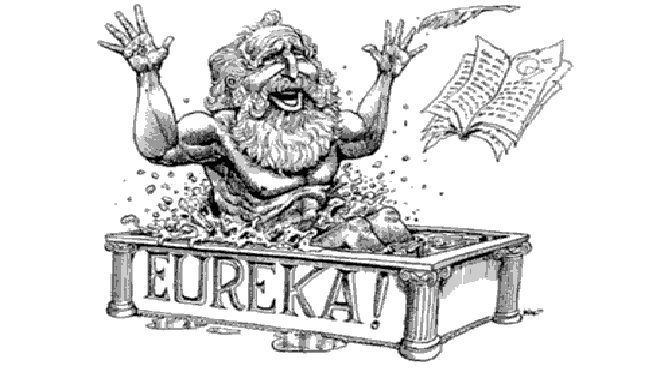

Throughout his life, Archimedes was deeply engrossed in study and research. Legend has it that he discovered the principle of buoyancy while bathing. He joyfully jumped out of the bathtub, ran straight to his workshop without even getting dressed, exclaiming loudly: “Eureka! Eureka (I have found it! I have found it!). During the war of Greece against the Roman invaders, Archimedes invented many new weapons, such as the catapult and ship hooks, particularly a type of optical weapon to burn enemy ships. The city of Syracuse was protected for three years before it fell. When the invaders captured the city, they found him still engrossed in studying drawings on the ground. He shouted: “Do not erase my drawings!” before being fatally struck by a spear. Archimedes heroically sacrificed himself like a valiant warrior.

Archimedes’ Strategies Against Invasion

In ancient Greece, wars frequently erupted among small states. Archimedes, in the small land of Syracuse, faced an invasion. Even at the age of 73, he participated in defending his homeland with all the intelligence of a scholar.

The enemy forces were extremely powerful, with 60 ships rushing towards Syracuse. Archimedes calculated and designed a type of stone-throwing catapult that could hurl stones weighing hundreds of kilograms. When the enemy drew near, Archimedes commanded, “Fire!” Many warships were damaged, and the enemy fled in fear.

After suffering losses, they had to retreat and discussed how to attack again at night. When night fell, the enemy ships quietly approached the city, setting up ladders and preparing to breach the city gates. Archimedes commanded his soldiers to prepare the catapults, but this time they were different. As the enemy approached, the stones were shot high into the sky and then fell straight down, striking the ships and soldiers, with one stone hitting the commander directly.

The enemy, driven mad, had to accept defeat once again. Yet, they were unwilling to concede completely and launched a third attack. This time, he requested that every woman bring her mirror to gather on the beach.

The enemy general, seeing many women, ordered the ships to advance in preparation for an attack. Little did they know that the mirrors would converge light and burn the sails and the ships. From the commanding officers to the soldiers, everyone was terrified, forcing them to retreat.

More than two thousand years have passed since Archimedes was killed by the Romans, yet people still remember him as a patriotic scholar, full of innovative ideas in both theory and practice, a man who devoted his entire life to science and his country until the very last moment.

His Discoveries

- The formulas for calculating the area and volume of prisms and spheres.

- The decimal approximation of Pi. In 250 BC, he proved that Pi lies between 223/7 and 22/7.

- A method for approximating the circumference of a circle using inscribed regular hexagons.

- The properties of the focus of a parabola.

- The invention of the lever, the Archimedes screw (possibly by Archytas of Tarentum), and the gear wheel.

- Creation of war machines when Syracuse was besieged by the Romans.

- Creation of the Archimedes spiral (possibly by Conon of Samos).

- Calculating the area of a parabola by dividing it into an infinite number of triangles.

- The principle of hydrostatics, Archimedes’ principle, and the barycenter.

- The Archimedean solids.

- Early forms of integration.

Many of his works remained unknown until the 17th and 19th centuries, when Pascal, Monge, and Carnot built upon Archimedes’ contributions.

His Written Works

- The equilibrium of floating bodies.

- The equilibrium of planes in mechanical theory.

- The method of centers of gravity of a parabola.

- Spheres and spherical volumes. This work established the area of a sphere in relation to its radius and the surface area of a cone from its base area.

- The spiral (known as the Archimedean spiral, as many types of spirals exist).

- The cone and sphere (the volume generated by the rotation of a plane around an axis, surfaces of revolution, parabolas rotating around a line or hyperbola).

- The circumference of a circle (he provided an approximation for Pi discovered by Euclid).

- A treatise on methods for discovering mathematics. This book was only discovered in 1889 in Jerusalem.

- On the center of gravity and planes: this was the first book written about the barycenter (literally meaning “heavy center”).

Archimedes – I Have Discovered It!

One day, the king of ancient Greece wanted to create a new and beautiful crown. He summoned a jeweler, presenting him with a shining ingot of gold and requesting that he quickly craft a crown for the king.

Not long after, the crown was completed, exquisitely crafted and beautiful. The king was very pleased and wore it while walking back and forth in front of his nobles. At that moment, a whisper was heard: “Your Majesty’s crown is beautiful, but is it made entirely of real gold?” Upon hearing this, the king summoned the jeweler and asked, “Is the crown you made for me made entirely of gold?“

The jeweler suddenly turned red, bowed, and replied to the king, “Your esteemed majesty, the amount of gold you gave me was just enough, neither more nor less. If you do not believe me, Your Majesty can weigh it again to see if it matches the weight of the ingot you gave me.”

The nobles weighed the crown, and indeed it was not lacking, so the king reluctantly allowed the jeweler to leave. However, the king knew that the jeweler’s words were hard to trust because he could have used silver to replace gold with equivalent weight, which would not be detectable by appearance.

The king, troubled by this, spoke to Archimedes, who responded, “This is indeed a difficult problem; I will help you clarify this matter.“

Once home, Archimedes weighed the crown and the ingot, and they matched in weight. He placed the crown on the table, examining it and thinking so deeply that he did not even notice when his servant called him to eat.

He thought: “The crown weighs exactly the same as the ingot, but silver is lighter than gold. If the crown contains an amount of silver equal to the amount of gold removed, then this crown must be larger than a crown made entirely of gold. How can I determine which has a larger volume, the crown or the ingot? Should I make another one? That would be a great waste of effort.” Archimedes thought again: “Of course, I could melt the crown down and cast it into an ingot to compare its size with the old ingot, but surely the king would not agree. It’s best to think of another way to compare their volumes. But what method?“

The intelligent Archimedes suddenly became quiet, as he racked his brain but still could not find a solution. He often sat silently for hours, and people said he was “stuck.”

One day, while taking a bath, Archimedes was so lost in thought that the water began to fill the tub to the brim. As he stepped into the bathtub, the water overflowed, and the more he submerged himself, the more water spilled out. Suddenly, Archimedes had an epiphany; his eyes lit up as he observed the water spilling over and wondered: Could the amount of water that overflowed equal the volume of his body submerged in the water? He was overjoyed and immediately filled the tub again, stepping in once more, and then repeated the process. Suddenly, he burst out of the room, clapping his hands and exclaiming: “Eureka! I’ve discovered it, I’ve discovered it!” forgetting to even put on his clothes.

The next day, Archimedes conducted an experiment in front of the King and the nobles, including a goldsmith for everyone to witness. He dropped a crown and a gold bar of equal weight into two water-filled containers of the same volume, then collected the overflow in two separate vessels. The results showed that the water displaced by the crown was significantly greater than that displaced by the gold bar.

Archimedes declared: “Everyone has seen it. Clearly, the crown displaces more water than the gold bar. If the crown were entirely made of gold, the amount of water displaced on both sides would be equal, meaning their volumes would be the same.“

The goldsmith had no further excuses, and the King angrily punished him. However, he was also relieved because Archimedes had helped solve this difficult problem for him.