At the end of the 19th century, three brilliant inventors in the United States—Thomas Edison, Nikola Tesla, and George Westinghouse—engaged in a “war” where each believed they were in the right.

The contentious topic they debated was whether a system built on direct current (DC) or alternating current (AC) would become the standard for electrifying the entire country.

The Origin of the “War of Currents”

In a series of disputes later known as the “War of Currents,” Edison, Tesla, and George Westinghouse each contributed to laying the groundwork for the electrification of America.

Leading the charge was Edison, who pioneered research and inventions related to the direct current system—where electricity flows steadily in one direction. In contrast, both Tesla and Westinghouse promoted their theories regarding the alternating current system—where electricity continuously alternates, which they viewed as an improvement over direct current.

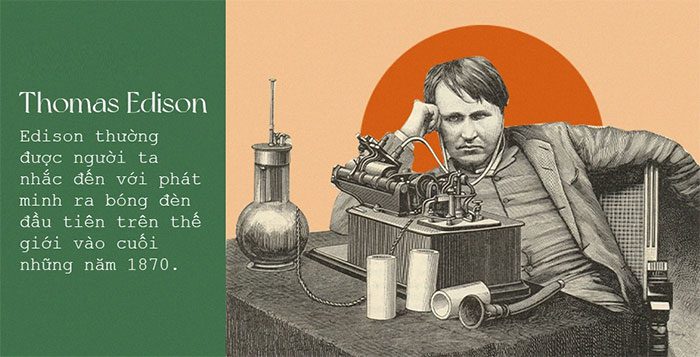

Edison is often remembered for inventing the first light bulb in the late 1870s. Following this achievement, he began to develop a system for generating and distributing electricity so that businesses and households could utilize his new invention.

The system Edison created included: a steam-powered direct current generator, transmission lines, switches, and measuring devices for energy consumption. In 1882, he opened his first power plant in New York City.

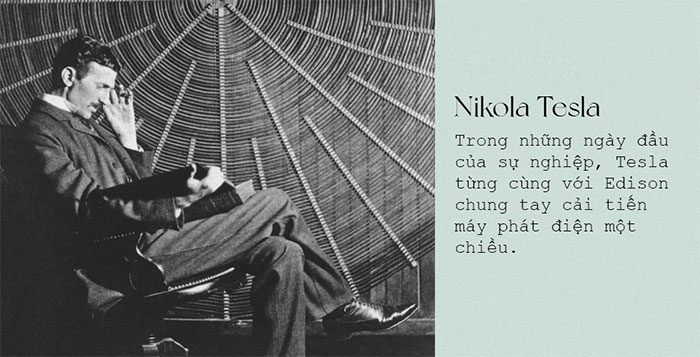

Meanwhile, Nikola Tesla had a much humbler beginning as a young engineer from Croatia who immigrated to the U.S. and worked in Edison’s factory. In the early days of his career, Tesla collaborated with Edison to improve the direct current generator.

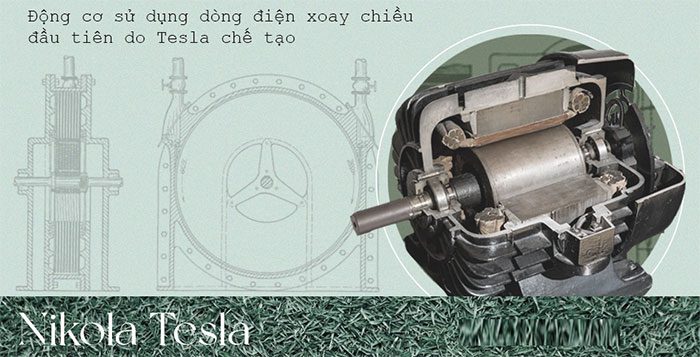

However, he later sought to garner interest from employers for the alternating current motor system he developed. At that time, the initiative of the “apprentice boy” was dismissed by Thomas Edison, who was dubbed the “Wizard of Menlo Park.” Edison firmly asserted that alternating current would “have no future,” insisting on his unwavering support for direct current inventions.

Stubborn and strong-willed, Tesla could not tolerate the conflict of opinions. He resigned in 1885 and continued with his own projects. A few years later, he received several patents for his alternating current system.

In 1888, Tesla sold his patents to American entrepreneur and engineer George Westinghouse—who was considered a pioneer in the 19th-century electrical industry. Due to breakthroughs in alternating current technology, Westinghouse Electric Company quickly became Edison’s number one competitor.

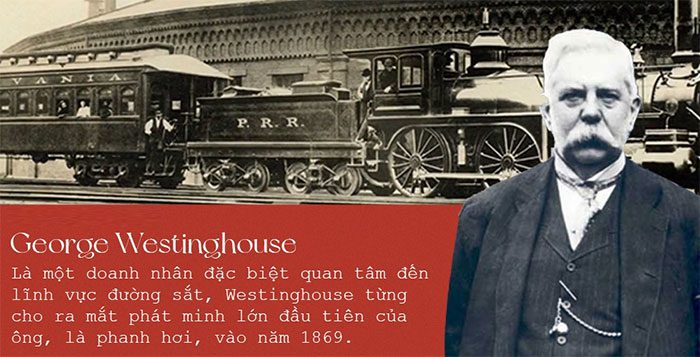

When it comes to George Westinghouse, no one denies his talent and genius. Unlike Tesla, who was purely an inventor, Westinghouse knew how to bring inventions to the public in various ways, quite similar to Edison.

A businessman with a keen interest in railroads, Westinghouse introduced his first major invention, the air brake, in 1869. He later added his own inventions to the patents he acquired, developing a complete system of electric and pneumatic signaling. Based on his knowledge of air brake systems, he began researching a safe natural gas pipeline system in 1883.

In 1884, Westinghouse recognized the potential of electricity and soon established the Westinghouse Electric Company. At that time, the entire electrical transmission system developed in the U.S. relied solely on direct current. However, Westinghouse quickly identified the shortcomings of this system and successfully persuaded Tesla to join his company after noticing his disagreements with Edison.

This decision by both men changed the landscape of the “war,” making alternating current systems popular and ultimately replacing Edison’s direct current.

Who Had the Greater Vision?

For scientists and inventors, it is challenging to clearly delineate who was the greater visionary. However, in the famous “war of currents” throughout American history, it is apparent that Edison was not particularly wise in his belief in the simpler yet less efficient direct current system.

A noticeable drawback of the direct current transmission system is that it causes energy loss and voltage drop along the conductors. It forced managers to build power plants in close proximity, within a range of only 1 kilometer or less.

In large cities, this model faced a few obstacles related to pollution and noise; however, in rural areas, deployment was nearly impossible due to the vast distances between communities.

In reality, Edison’s so-called “landmark” inventions also sparked controversy, as some argue that he was merely lucky, having moved “one step faster” than contemporaneous scientists, rather than being as talented as the media portrays.

“While the light bulb, phonograph, and motion picture projector are regarded as Edison’s most significant inventions, several scientists of his time were also researching similar technologies,” said Leonard DeGraaf, an archivist at the Thomas Edison National Historical Park in New Jersey. “If Edison hadn’t invented those things, someone else would have.”

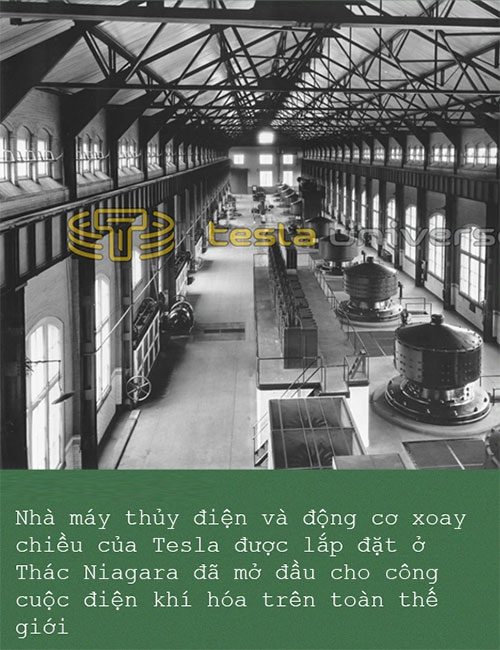

Conversely, Tesla’s ideas were often groundbreaking technologies ahead of their time and not currently demanded by the market. His hydroelectric power plant and alternating current motor installed at Niagara Falls marked the beginning of global electrification; or his wireless voice and image transmission system contributed to the technological foundation for radio, telephones, and TVs. Some of Tesla’s ideas even surpassed the understanding, knowledge, and technology of humanity at the time.

Of course, Westinghouse had no difficulty recognizing the genius behind Tesla’s alternating current. He elevated the alternating current system, making it more advanced, flexible, and technically cheaper than Edison’s contemporary system.

Certainly, Edison at that time also felt threatened by the powerful rise of alternating current, which could be distributed over much greater distances than his direct current. However, Edison did not want to admit his mistakes. He publicly led a large-scale propaganda campaign to undermine the credibility of the alternating current system and convinced the public that this current was very dangerous.

The great inventor even gathered evidence, claiming that many animals electrocuted in the area were a result of using alternating current. When New York officials publicly sought a solution to replace hanging as a form of execution for death row inmates, Edison immediately suggested they use alternating current, asserting that this current was extremely dangerous and could kill quickly.

As a result, William Kemmler, a convicted murderer, became the first person to die in the electric chair due to a system designed by Westinghouse’s alternating current generator. However, the incident backfired on Edison, and he clearly failed in his attempt to discredit alternating current.

This shows that although recognized by humanity as a great inventor, there were times when Edison’s vision was hindered by his own inflated ego. Worse still, he resorted to various means to impede his “rival” instead of openly acknowledging the advancements in science.

Thomas Edison’s Foreseen Downfall

What was inevitable eventually came to pass. Systems utilizing alternating current gradually proved their capability and superiority over direct current. A striking example is that Westinghouse’s company won the bid to provide electricity for the World’s Fair held in Chicago, USA, in 1893.

The dazzling spectacle at that time truly marked the end of a decades-long dispute among the three brilliant inventors. That same year, Westinghouse’s company signed a contract to build an alternating current power generation system for the world’s first hydroelectric power plant at Niagara Falls in the U.S. in 1895. Out of the 12 patents used to build the plant, 9 belonged to Tesla.

It is hard to imagine what the world would look like today if, in the past, Edison had successfully “suppressed” Tesla’s invention of alternating current, leading to a more refined version of direct current. However, Jill Jonnes, author of the book “Empires of Light: Edison, Tesla, Westinghouse and the Race to Electrify the World”, provides us with an intriguing perspective on this hypothesis.

“If we were living in Edison’s world, we would have to place a coal-powered power plant every one or two miles, because direct current cannot be transmitted over long distances,” Jonnes explains. “The strength of alternating current is that you can send it over very long distances, step it down through a transformer, or even distribute it to neighboring areas as needed.”

Jonnes also emphasizes that “Once Tesla solved the problem of how to create a motor that could operate on alternating current, that was when the outcome between him and Edison was settled.”

Of course, the failure in the battle of currents did not turn Edison into a “loser of the century.” His later inventions, such as the motion picture camera and the Kinetoscope, helped him regain his leading position in his inventive career.

“The point I always want to make about Edison, as to why he is the most famous inventor, is that we all understand his inventions and live in the immeasurable conveniences they provide,” Jonnes expresses.