These two mysterious celestial bodies are the “siblings” of Pluto.

One of the missions assigned to the world’s most powerful space telescope, the James Webb Space Telescope, is to search for “biosignatures” in distant celestial bodies, including worlds far beyond our Solar System. However, it has just made a surprising discovery.

Right within our Solar System, the James Webb has detected signs of methane—one of the potential biosignatures—on two of the most seemingly inhospitable worlds.

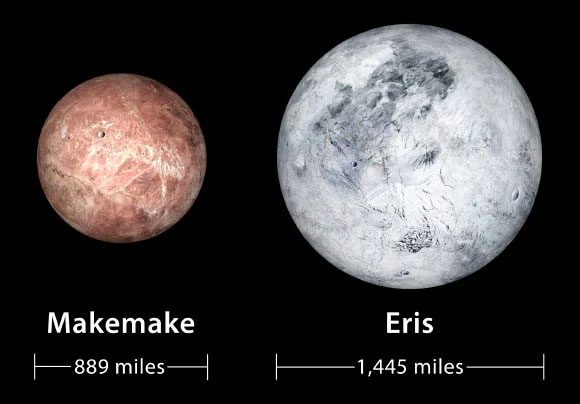

These are Eris and Makemake, two dwarf planets belonging to the class of Plutoids, meaning they share many characteristics with Pluto.

Two celestial bodies recently identified as having signs of hydrothermal activity – (Photo: NASA).

Wandering in the icy wasteland beyond Neptune’s orbit, the presence of methane on these celestial bodies raises many questions.

“We see some intriguing signs of a warm period in these cool places” – Sci-News quoted Dr. Christopher Glein from the Southwest Research Institute (SwRI).

Initially, the authors believed that methane could exist in these locations because it was available in the primordial materials that formed these celestial bodies, inherited from the solar nebula.

However, detailed data from the James Webb has brought surprising evidence: proof of hydrothermal processes generating methane from within these planets.

This is reflected in the ratio of deuterium (heavy hydrogen – D) to regular hydrogen (H) in the detected methane.

If the D/H ratio is high, the methane is primordial material with deuterium that formed abundantly during the Big Bang.

But the D/H ratio on these two celestial bodies is moderate, indicating that the methane formed through geochemical processes.

This is a process similar to that on Earth, where the rocky core undergoes significant radiative heating, remaining warm enough to sustain hydrothermal processes and generate methane, which is then brought to the surface.

Additionally, the concentration ratios of certain carbon isotopes indicate relatively recent resurfacing on both Eris and Makemake. They are not the “dead” rocks that were previously thought.

On Earth, hydrothermal systems are the “springs of life.” They exist at the ocean floor, providing warmth and essential chemical components for life to emerge and thrive.

There is a theory that hydrothermal systems were where life began on Earth.

It’s still too early to assert anything about worlds so distant, drifting in the icy “outskirts” of the Solar System like Eris and Makemake.

However, scientists hope that some future NASA missions will get closer to these celestial bodies in this area that Dr. Glein believes is “more lively than we think.”