Walking at high altitudes can lead to altitude sickness, but what happens to those who venture deep inside the Earth?

In the past, miners and civil engineers were often required to walk deep underground, where their bodies faced atmospheric pressure that was double that on the surface. The damage it caused to the body could sometimes be severe, even fatal. So, what does it feel like to go deep into the Earth?

Despite being in the 21st century, there are still many mysteries that humanity dreams of exploring.

The largest known rare earth metal mine in Europe was discovered by a mining company in Sweden, near the Kiruna iron ore mine, which is the largest of its kind. Writing for NPR, international affairs reporter Jackie Northam explained what it feels like to undertake a 30-minute journey into the base of the iron ore mine.

“Your skin becomes noticeably drier, your ears ring, and it’s hard to shake off the feeling of isolation as you walk down the dark path, guided only by the reflective panels on the fortified gray stone walls of the tunnel. Eventually, when you reach the bottom, over 4,000 feet (1,219 meters) below the Earth’s surface, you will discover a complex of brightly lit offices, a self-service cafeteria, and even a car wash.”

The symptoms may sound familiar to anyone who has ever flown, except that flying takes you high up in the sky, while this journey takes you straight down into the Earth.

In a 2008 article, scientists described the deepest levels beneath the Earth’s surface that humans can reach:

The deepest of these is the Mponeng gold mine, formerly known as the Western Deep gold mine, located in Johannesburg, South Africa. According to the Guinness World Records, “In 2012, the mining depth reached 3.9 km below the surface, and subsequent expansions led to drilling below the 4 km mark.”

At this depth, miners are battling rapidly increasing temperatures with depth. The rock walls can reach temperatures of up to 60°C, and humidity can exceed 95 percent, but mitigation measures such as rock mud and ventilation systems have been used to lower these temperatures to acceptable levels.

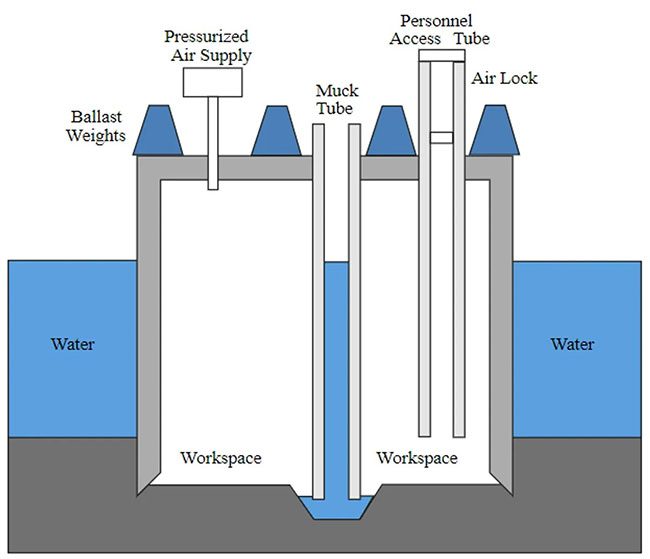

Bridge builders must work in high-pressure air conditions to excavate sediments without water flooding in.

However, temperature is just one factor; one of the greatest challenges that humans face when going deep underground is high pressure.

In fact, there have been many deaths during the construction of the Brooklyn Bridge in New York City, many of which were victims of caisson disease, also known as decompression sickness (DCS). Many might think this disease only affects divers, but in reality, the first diagnosed cases were among miners and bridge builders.

According to information from History, these deaths due to the disease originally occurred among urban miners and construction workers working underground on various excavation projects in New York City. As the workers dug deeper, their bodies experienced increasingly severe symptoms, including muscle paralysis, slurred speech, joint pain, and stomach cramps.

The symptoms of exhaustion were first called caisson disease because those affected were digging inside rooms of the same name submerged deep beneath the East River. They were a crucial part of the bridge’s construction, as sediments were excavated from the caissons until the hollow shaft was finally filled with concrete.

Pressure injuries occur from moving from high-pressure areas to low-pressure areas in a short period. For this reason, it is also known as decompression sickness, and today it commonly affects divers, pilots, astronauts, and those working in compressed environments.

Moving from a high-pressure area, such as the deepest part of a mine, to a low-pressure area, such as the surface, can create nitrogen gas bubbles in the body. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), when the pressure change and gas release into the body occur too quickly, it can be extremely painful and sometimes fatal.

Common symptoms of decompression sickness (DCS) include joint pain, bone necrosis, mottled skin, strokes, paralysis, shortness of breath, and arterial gas embolism… The good news is that if this condition is diagnosed early, it can be treated using a hyperbaric chamber. This effectively recreates the slow movement from one pressure state to another.