The Moons of Failed Planets may harbor extraterrestrial life forms similar to those found in Earth’s hydrothermal vents.

A new study led by astronomer Patricio Javier Ávalos from the University of Concepción (Chile) has modeled the potential existence of “exomoons” orbiting “failed planets.”

Could the moons of lonely planets harbor extraterrestrial life? – (Photo: BBC)

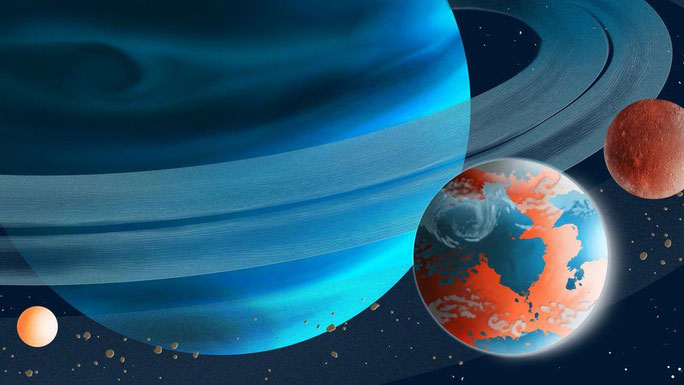

Failed planets are worlds that resemble gas giants but drift aimlessly through the universe without orbiting any star. There are several theories surrounding this state of loneliness: they may have been ejected from their “solar system,” or they once had a companion star that has since died. There is also a theory that suggests

According to the Daily Mail, a new analysis shows that moons orbiting failed planets typically receive a certain amount of cosmic radiation that allows them to convert hydrogen and carbon dioxide into liquid water. The water present would be less than 10,000 times that of Earth’s oceans but more than 100 times that found in the atmosphere. This amount is still sufficient for extraterrestrial life to thrive.

Failed planets often possess a strong enough gravitational field to create tides on their moons, similar to how Jupiter influences its “habitable moons” like Europa and Ganymede, enabling the planet to maintain conditions suitable for life. These planets are also not as hot as stars, so even if the moons are close, they would not be scorched like planets too near to their parent star.

According to Science Alert, another challenge is light. However, in recent years, scientists have continuously discovered bizarre worlds with life forms that can exist without light right here on Earth: in hydrothermal vents on the ocean floor, underground, and beneath permafrost. Extraterrestrial life on exomoons in our solar system, such as Europa or Enceladus, is also expected to be of this type, as they exist beneath a subsurface ocean covered by a permanent ice shell.

Therefore, even though the moons of failed planets are “dark moons,” they still have the potential to support life.

The study was recently published in the scientific journal International Journal of Astrobiology.