According to The Guardian, scientists are warning that the world is facing a “potential crisis” in the production of phosphate fertilizer, a crucial fertilizer that underpins the global food supply.

What is Phosphorus?

Phosphorus is one of the six chemical elements that make up all living organisms. The framework of DNA and RNA, cell membranes, bones, and teeth all require phosphorus.

Unlike other essential elements for life—including oxygen, hydrogen, carbon, nitrogen, and sulfur—inorganic phosphorus cannot be found in its elemental form in nature; it exists in insoluble minerals. As a result, plants and animals can only obtain phosphorus through other organisms, dead tissues, or their waste.

Phosphorus exists in three basic colored allotropes: white, red, and black. Other allotropes may also exist, but the most common forms are white phosphorus and red phosphorus.

Inorganic phosphorus cannot be found in its elemental form in nature.

The average human body contains 1 kg of phosphorus, enough to produce hundreds of matchboxes. Phosphorus is unevenly distributed in the body, with the highest concentration in bones, around 100g in muscles, and nearly 10g in nervous tissue.

Farmers supplement phosphorus in large quantities to ensure bountiful harvests. However, phosphate mines are a finite resource.

Moreover, the largest supply is located in politically unstable regions, posing risks for many countries with little or no phosphate reserves.

Changing the History of Global Agriculture

Phosphorus has been a key factor in the rapid increase of the world’s population over the past two centuries. According to Sputnik, in the 1840s, British geologists discovered phosphorus-rich coffee-colored round stones in sedimentary rocks near Cambridge.

In the following decades, over 2 million tons of phosphate rock were mined. The fields and marshes in southeastern England became construction sites with countless pits and tunnels. The ore was sorted, washed, and transported to specialized factories for grinding and treatment with acid. The end product of this process was superphosphate—the world’s first chemical fertilizer.

Phosphate ore revolutionized global agriculture. For the first time in history, humans could produce food almost everywhere on the planet, wherever there was water for irrigation. Since then, Earth’s population has rapidly increased, and humanity has gradually become heavily dependent on fertilizers.

Phosphorus exists in three basic colored allotropes: white, red, and black. (Photo: Sputnik)

And hundreds of geologists continue to search for “fertile rocks” around the world.

Massive phosphate deposits have been found in Western America, China, the Middle East, Europe, Africa, and Australia, as well as beneath the Atlantic Ocean and the Baltic Sea. This became extremely important in the 20th century during the Green Revolution, when high-yield crops became widely cultivated.

Phosphorus is Gradually Depleting

The use of phosphate fertilizers has quadrupled in the past 50 years as the global population has increased, and the depletion of this resource is approaching as new analyses emerge regarding human consumption. Some scientists predict this moment could arrive within a few decades at the earliest.

Researchers state that humans can only produce half of the food supply without phosphorus and nitrogen, even though nitrogen is essentially infinite since it makes up nearly 80% of the atmosphere.

Martin Blackwell, an expert at Rothamsted Research, an agricultural research center in the UK, and the lead author of a new study, stated: “The supply of phosphorus could be a very big issue. The population is increasing, and we will need more food.”

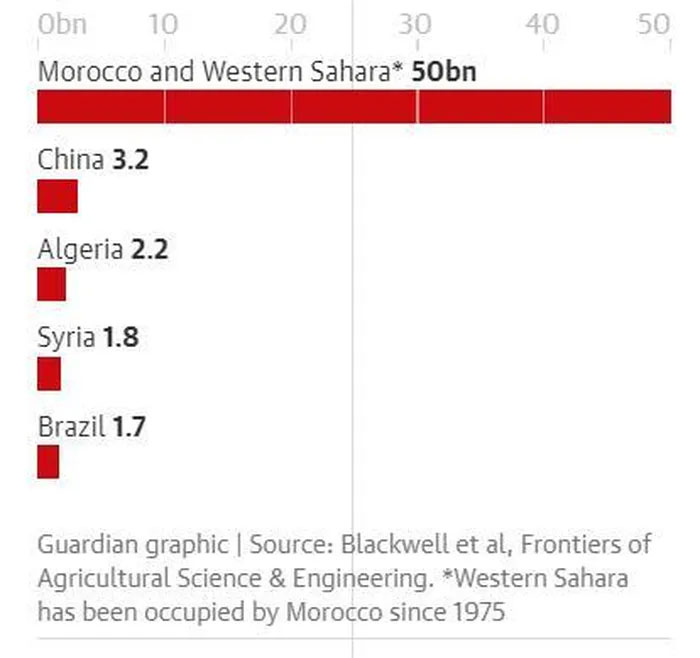

The world has 70 billion tons of phosphorus, with the five largest reserves accounting for 60 billion tons. Morocco and Western Sahara far exceed other regions with 50 billion tons. Graphic: The Guardian

At the current rate of use, many countries will deplete their domestic supplies in the next generation, including the United States, China, and India. Morocco and the territory it occupies in Western Sahara have the largest reserves, followed by China, Algeria, and Syria.

Mr. Blackwell said: “In the coming years, this could become a political issue as some countries may control global food production by tightening the supply of phosphate rock. It is time to recognize this issue. This is one of the most important issues in the world today.”

Feasible solutions include recycling fertilizers from human wastewater, manure, and slaughterhouse waste, developing new crop varieties that can absorb minerals from the soil more efficiently, and improving soil quality testing to avoid over-fertilization and waste.

Excessive use of phosphate fertilizers not only depletes supplies but also causes widespread pollution, leading to dead zones in rivers and seas. In 2015, a study published in the journal Science cited phosphorus pollution as one of the most serious issues facing the planet, even more so than climate change.

A new study published in the journal Frontiers of Agricultural Science and Engineering assessed: “Continuing to use phosphate fertilizers as the foundation for global food production poses the risk of a crisis.”

The study noted that, according to estimates, phosphate rock supplies have decreased from 300 to 259 in just the past three years due to increased demand. Scientists wrote: “If supplies continue to decrease at this rate, it cannot be ruled out that all supplies will be depleted by 2040.”

A real “phosphorus disaster” erupted in 2008 when, amid the global economic crisis and rumors of dwindling raw material supplies, phosphate prices surged by 800%.

Historically, phosphate fertilizers have always been cheaper than potassium or nitrogen fertilizers, which require natural gas for production. As a result, low- and middle-income countries have increasingly depended on imported phosphate fertilizers. When phosphorus became expensive, many countries in Africa and Southeast Asia faced severe hunger in the 21st century.

The situation has worsened in recent months. Supply chain disruptions, export bans, and sanctions against Russia have caused global phosphate prices to quadruple.

Finding Alternative Sources

Changing the way phosphorus is used and recycled globally will be essential. In particular, China, India, and the United States—the three countries with the largest populations on the planet—will need to pay the most attention.

The European Commission declared phosphorus to be “a critical raw material” in 2014, indicating that it is an essential resource with significant supply risks. Only Finland has phosphate rock reserves in the EU, while most other member countries must import this material from Morocco, Algeria, Russia, Israel, and Jordan. “The EU is heavily dependent on regions currently experiencing political crises”, according to the EC report.

Changing the way phosphorus is used and recycled globally will be essential.

Commercial phosphate fertilizers were invented at Rothamsted in 1842 by dissolving animal bones in sulfuric acid. Blackwell and his colleagues have returned to researching this source to create an alternative phosphorus supply.

They have synthesized bones, horns, blood, and other slaughterhouse waste into phosphate fertilizer, and a new study shows that this compound performs equally well or better than conventional fertilizers. Mr. Blackwell stated that they could supply 15-25% of the UK’s needs. Another potential source is extracting phosphorus from human wastewater.

Recycling phosphorus from animal and human waste is crucial, but this will take time to implement as new technologies and regulations will be necessary to ensure no environmental contamination occurs and to protect food crop products.

Blackwell noted that reducing phosphorus use is also key. Phosphorus expert Marissa de Boer stated that the public’s lack of awareness means that the environmental crisis issue is not well known: “We are truly dependent on phosphorus, but we take its use for granted.”