To continuously push the limits of performance, semiconductor engineers have discovered a simple method: making chips larger.

While chip manufacturers like TSMC and Samsung are racing to create smaller chip processes, the entire chip industry is following a new strategy to enhance the power of these processors: making them larger. Much like urban areas expanding, many of the chips inside our most powerful devices are now occupying so much space that they can no longer be referred to as “microchips”.

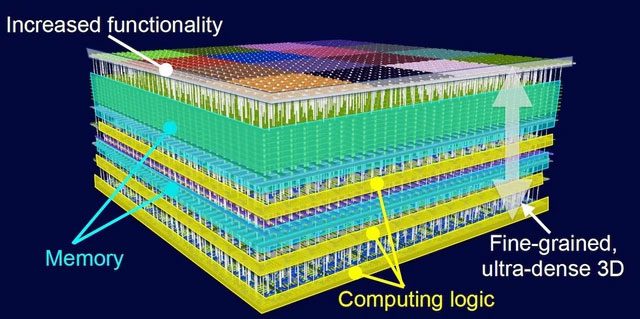

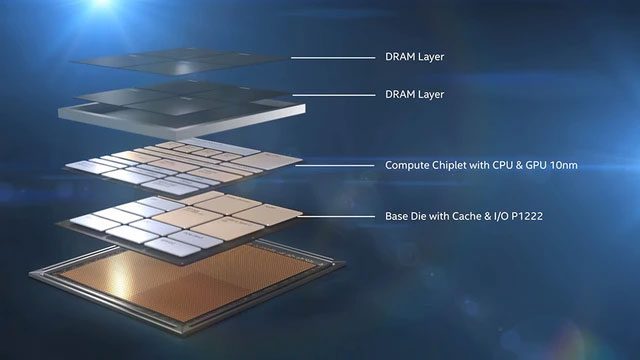

To expand processing capabilities, semiconductor engineers are looking to stack these microcircuits on top of each other. This means that instead of merely stacking transistors into towering apartment blocks, entire flat silicon wafers inside computers—such as memory chips, power management chips, and graphics chips—are being layered in various ways.

The reason behind this chip design trend is straightforward: the demand for faster and more feature-rich chips continues unabated, and the chip industry’s ability to meet these requirements by shrinking transistors further has encountered numerous technical barriers.

Semiconductor engineers are looking to stack these microcircuits on top of each other.

As a result, semiconductor engineers are increasing their performance by bringing these chips even closer together. Similar to highways connecting cities, as this distance shortens, data moves between them more quickly, thereby improving processing capabilities. Consequently, in many cases, these meticulously carved silicon urban areas have grown to sizes rarely seen in chips.

Currently, most chips are roughly the size of a small coin, but some new chips are equivalent to a playing card, and in some instances, there are chips the size of a disc.

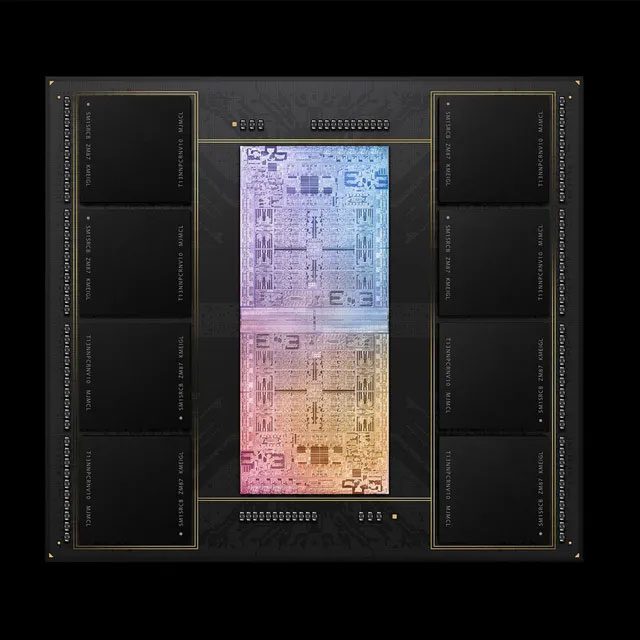

Not only are these chips present in the world’s most powerful supercomputers, but they are also found in consumer electronics. Microsoft’s new Xbox gaming console and Sony’s PS5 both utilize processors designed by AMD. Apple has also leveraged this design for the M1 Ultra processor in their Mac Studio computers. This approach has also been employed by Intel for its Ponte Vecchio processors used in supercomputers and data servers.

This does not imply that they are violating Moore’s Law. Chips may not be cheaper, as stated by Intel’s co-founder, but their performance and features are continually improving. Even ASML, the company that produces the world’s most advanced chip manufacturing machines, believes that to maintain the pace of Moore’s Law, simply shrinking transistors in chips is insufficient.

Apple’s M1 Ultra chip, essentially two M1 Max chips combined to enhance performance.

Stacking Cities and Connecting Them by Elevators

Similar to urban development, if a city cannot further reduce the size of houses or make transportation more efficient, it has no choice but to expand outward. A clear example is Singapore, whose land area has expanded by 25% over the past 50 years.

Making super-large chips is equally challenging as shrinking them. Just imagine arranging each component of a chip with nanometer-level precision and connecting them together without any tiny soldering tools.

This is made possible through recent advancements in the process critical just after the chip lithography stage: chip packaging. People often overlook this stage, but it is an essential part of chip manufacturing. At this stage, manufacturers aim to connect ultra-fine wires within the chips and encase them in plastic before placing them onto circuit boards to connect with the rest of the device.

The N3XT system, an idea for 3D packaging of memory chips and processing chips presented by TSMC in 2019.

In traditional devices, a chip that sends and receives radio waves (e.g., a Wi-Fi chip) can connect to another chip to perform calculations, and this connection is referred to as a “bus”. Much like a bus traveling on a highway connecting cities, these “buses” struggle to transport anything quickly.

However, with the new chip packaging method, these independent chips are directly connected to become super chips. Instead of connecting through “buses,” these chips are stacked together as if they are in the same skyscraper.

According to Subramanian Iyer, former director of IBM’s Packaging Division, a typical microchip dedicates nearly one-third of its area—along with its energy consumption—to circuits that transmit the chip’s computational results to the rest of the device. This, of course, is inefficient for its power.

Stacked chips facilitate faster communication between them by allowing for more connections between them—much like taking an elevator between floors in a skyscraper is faster than walking across the street to reach the nearest neighbor.

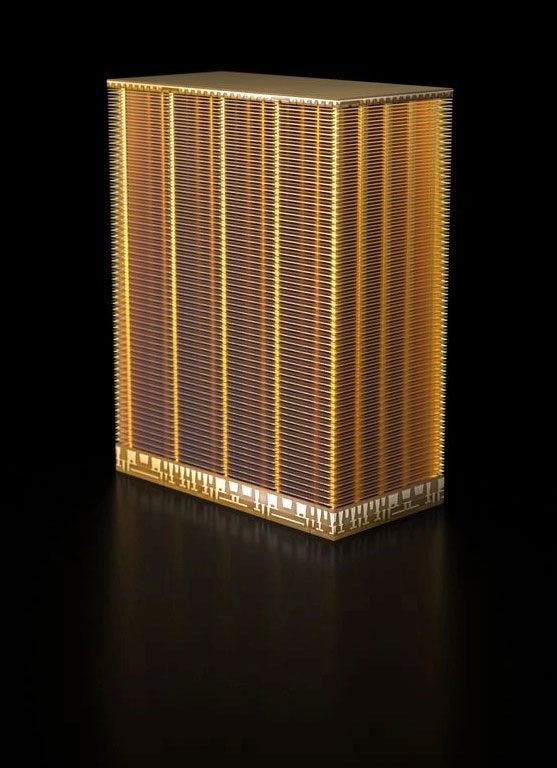

Micron’s 232-layer memory chip.

In fact, for memory chips, this has long been standard practice. Micron Technology introduced a memory chip with 232 layers. However, this design is now just beginning to extend to other types of microchips.

The foundation for creating these super chips and stacked chips is a new type of microchip called “chiplet.” It eliminates the old communication circuits to connect more directly with other chiplets. By creating short, direct connections—often made from the same silicon that forms the chips instead of other metal wires—these chiplets can be combined to form super chips and act as a massive processor.

A prime example is the recently introduced Ponte Vecchio graphics processor from Intel. It consists of 63 different chiplets. These chiplets are stacked and placed adjacent to each other, with a total area of 3,100mm2, including 100 billion transistors. In contrast, a typical laptop CPU has an area of about 150mm2, just 1/20th the size of this chip, and contains only about 1.5 billion transistors, a mere 1.5% of Ponte Vecchio’s count.

This stacked chiplet design is clearly the future for Intel—most of the processors the company has announced but not yet shipped are being produced with this technology, as it “provides a new approach to faster chip production that is more cost-effective than traditional methods,” said Debendra Das Sharma, a senior member of Intel.

Stacked chiplets also allow Intel to boost performance for desktop and server processors without increasing the chip’s footprint or power consumption. Indeed, stacked chiplets enable engineers to increase the number of transistors compared to current designs by optimizing the time and energy required for components within the chip to communicate with each other.

Intel’s 3D chip stacking technology Foveros introduced in the Intel Lakefield chip generation.

The pioneer of chiplet technology, AMD has also introduced processors with a small number of chiplets inside. The company realized that by stacking memory chips on top of their CPUs, they could significantly increase the computational speed of their processors.

Everyone on the Same Ship

According to Marc Swinnen, marketing director at Ansys, while super chips based on chiplets currently represent a small fraction and appear in large computing systems, the trend to create them is accelerating throughout the chip industry. Ansys is a company that builds physics simulation software widely used in chip design.

The company states that the number of projects initiated by Ansys customers related to stacked chiplets has increased twenty-fold since 2019.

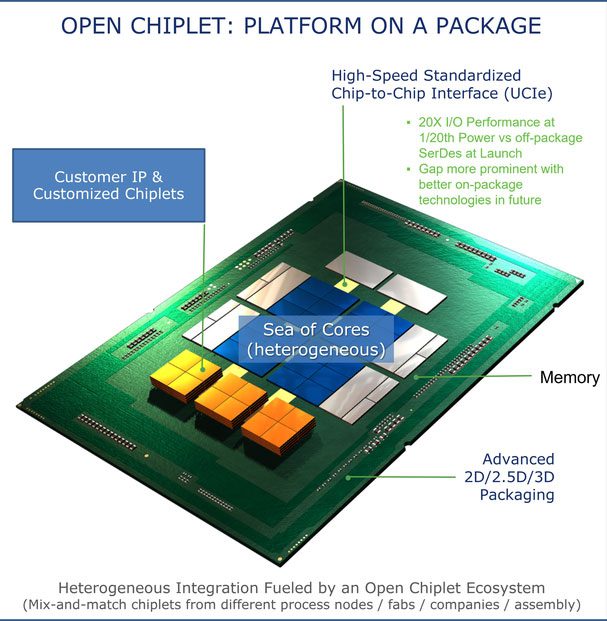

In March, a chip industry consortium named Universal Chiplet Interconnect Express, or UCIe, announced that it is collaborating with both Intel and AMD to develop a new standard. This standard will allow anyone involved to create chiplets that can connect with products from other manufacturers. In addition to Intel and AMD, this consortium includes ARM, TSMC, Samsung, and other chip design and manufacturing companies.

Open-source chiplet design standard version 1.0 from UCIe.

This standard has been established with the hope that in the future, any company will be able to purchase chiplets from another company and assemble them in any way they desire or according to their intended use. Imagine being able to select the best parts of New York, Rio, and Tokyo, and then piece them together into your dream city according to your preferences.

However, this very idea makes Dr. Kumar from the University of Illinois skeptical about the success of this standard: “Standardizing anything in this industry is an incredibly tough challenge, as there will have to be compromises, and not everyone is motivated to play nicely with others.”

The main driving force behind this technology is the increasing desire among major companies—including Amazon, Google, Tesla, Microsoft, and others—to create their own processors with growing power to operate everything: cloud services, smartphones, gaming consoles, and self-driving cars.

Additionally, according to Dr. Kumar, the interest in superchips also stems from the exponentially increasing demand to integrate machine learning and artificial intelligence systems directly onto the hardware. While some companies are meeting this demand by building gigantic chips in the traditional way—such as Cerebras’ AI chip, which is the size of an entire wafer—chiplets now offer a new method for constructing more powerful yet compact AI processors.

From Supercomputers to Wearable Devices

The enthusiasm for superchips is not limited to high-performance systems; it is anticipated that one day they will also be integrated into devices prioritizing battery life.

AMD’s chiplet platform is ready to connect with third-party chiplets.

According to Dr. Kumar, just as cities connect with suburbs through rapid transit systems, chiplets in the future could connect over greater distances and through newer means.

This may seem illogical since greater distances would increase communication and data processing times. However, it provides the benefit of allowing smaller chips to connect with more flexible circuits, leading to more adaptable computers. It may even enable the creation of entirely new types of computing devices.

Experiments conducted by Dr. Kumar’s team have shown that chiplets can connect through flexible circuits in wearable devices, or in systems that can wrap around surfaces like airplane wings. Moreover, Dr. Iyer noted that his team is also developing the necessary semiconductor blocks for flexible phones.

Despite the challenges that superchips still face, efforts to transform today’s breakthroughs in microchips into smaller, interconnectable chiplets are ongoing. Moore’s Law cannot continue to be sustained without it.