Both Othniel Marsh and Edward Cope discovered countless dinosaur fossils in the 19th century, but they were obsessed with the goal of undermining each other in the Bone Wars.

Othniel Charles Marsh and Edward Drinker Cope are two of the most renowned fossil hunters of the 19th century, according to National Geographic. They uncovered over 100 dinosaur species, including Stegosaurus, Triceratops, and Lystrosaurus, during the early days of paleontology. Their rivalry, known as the Bone Wars, led to significant scientific discoveries that shaped the field of paleontology. Despite their fame and success, they harbored a deep-seated hatred for one another. Their animosity ignited an all-out war, employing every tactic imaginable to secretly undermine each other, including bribery, deception, and slander.

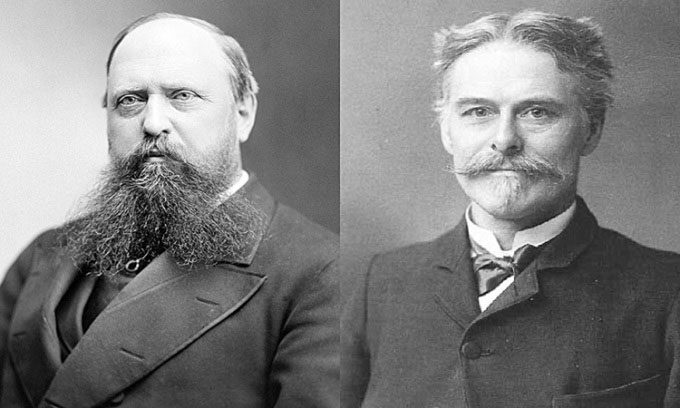

Othniel Charles Marsh (left) and Edward Drinker Cope (right). (Photo: Wikimedia).

Before becoming arch-rivals, Marsh and Cope were once friends. Othniel Marsh was born in New York in 1831 into a modest family. However, his wealthy uncle, George Peabody, funded his education. The young scholar graduated from Yale University with distinction. In contrast, Edward Cope was born in 1840 into a well-to-do family with a prominent standing in Philadelphia. The only challenge he faced was escaping the path his family had laid out for him. Cope’s father wanted him to become a genteel landowner, but he aspired to be a scientist.

In 1863, Cope’s father took him to Europe. In Berlin, he befriended a rising star in natural sciences, Othniel Marsh. As young American scholars abroad, they grew close in their shared enthusiasm for paleontology, a relatively new academic discipline focused on the study of ancient fossils. After returning to the U.S., the two corresponded and even named newly discovered species after each other. Cope named a species Ptyonius marshii, while Marsh named a species he discovered Mosasaurus copeanus.

However, a crucial issue emerged. Paleontology was still in its infancy, and its novelty sparked a competitive relationship between Marsh and Cope as they sought to establish themselves as leading researchers in the field. The race to assert their dominance strained their friendship. Some scholars believe their rivalry began in 1868 when Marsh visited Cope during a fossil-hunting expedition at a quarry in New Jersey. Marsh secretly arranged with the quarry owner to transport newly found fossils to him instead of Cope.

Cope’s biographer, Jane Davidson, argues that the feud originated the same year when Cope published a description of a newly discovered species, Elasmosaurus platyurus. While reconstructing the creature, Cope made a significant mistake by reversing the tail and neck of the animal. Marsh called Cope to criticize his colleague’s error. Humiliated, Cope hurriedly bought up the journal prints that published his discovery, but it was too late.

The American West was a fertile ground for prehistoric fossil exploration, but it was not large enough for both men. They eagerly sought fossils, striving to make greater discoveries than their rival. In 1871, Cope arrived at a site in Kansas that Marsh’s team had previously overlooked. He found the skeleton of a larger species of flying lizard than the one discovered by Marsh. Cope was thrilled, while Marsh was furious.

As the battle intensified, Marsh and Cope resorted to other measures to undermine each other, including accusations of plagiarism, espionage, and increased publications. Cope even purchased the journal American Naturalist, using it as a platform to criticize Marsh and his research. Their hostile relationship escalated as both brought associates to the excavation site at Como Bluff, Wyoming, from 1877 to 1879. Marsh even directed his associates to destroy any bones in the area before leaving, so Cope could not retrieve them.

The scientific war between these two paleontology experts lasted a decade. Nevertheless, the feud between Marsh and Cope contributed to the enhancement of human understanding of the world, driving their research efforts. Cope authored 1,400 scientific papers. Their endeavors helped identify over 130 extinct species. However, the battle came at a high cost. In 1892, Marsh’s superior at the U.S. Geological Survey demanded his resignation. Cope ultimately had to sell his fossil collection a few years before his death in 1897. The Bone Wars ruined both men.