A newly identified species of beaver – Microtheriomys actiulaquaticus, represents the oldest semi-aquatic rodent species in North America and is the oldest amphibious beaver species in the world.

The previously identified oldest semi-aquatic beaver was Steneofiber eseri, which lived in France around 23 million years ago. However, the archaeological community has now identified a new beaver species that is even older – Microtheriomys actiulaquaticus, which lived in what is now Montana, USA, approximately 30 million years ago (during the Oligocene epoch).

Microtheriomys actiulaquaticus did not have a flat tail like modern beavers, its diet was purely herbivorous instead of wood-based, and its size was relatively small.

Their diet was purely herbivorous.

Dr. Jonathan Calede, an evolutionary biologist at Ohio State University and the author of the study published in the Royal Society Open Science journal, stated: “Beavers and other rodent species can tell us a lot about the evolution of mammals.”

“Look at the diversity of life around us today, and you see gliding rodents like flying squirrels, jumping rodents like kangaroo rats, aquatic species like muskrats, and burrowing animals like moles.”

“There is an incredible diversity in form and ecosystem. And when that diversity arose is an important question in studying the evolutionary process of mammals.”

“Rodents are the most diverse group of mammals on Earth, and about 40% of all existing mammal species today are rodents. If we want to understand how we acquired such incredible biodiversity, rodents are an excellent system to study.”

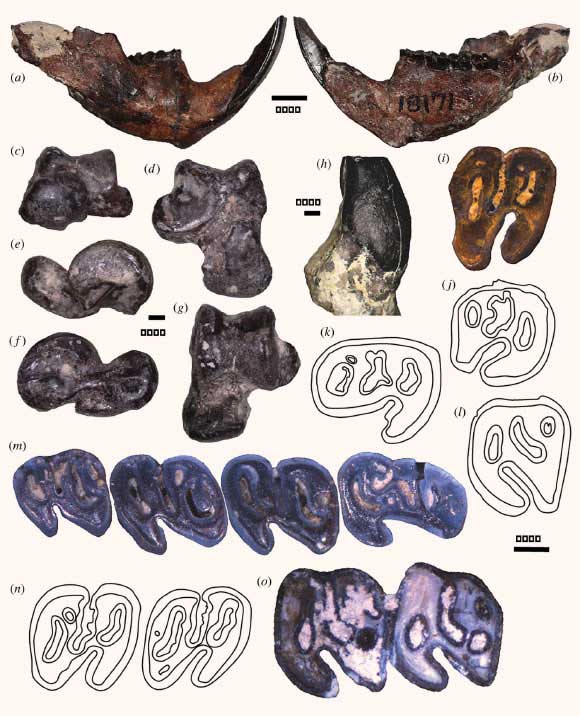

The fossil material of Microtheriomys actiulaquaticus—which includes several associated teeth, two astragalus bones, and a part of a bone—was recovered from the Renova Formation.

Dr. Calede performed 15 measurements of fossil ankle bones and compared them with measurements of similar bones from 343 specimens of living rodent species as well as relatives of ancient beavers.

Fossil material of Microtheriomys actiulaquaticus.

By running computational analyses on the data in various ways, he proposed a new hypothesis for the evolution of amphibious beavers, suggesting that they began swimming as a result of adaptations to a new habitat.

Dr. Calede stated: “In this case, the adaptation for burrowing was co-selected to transition to a semi-aquatic mode of locomotion.”

“The ancestor of all beaver species that ever existed was likely a burrowing species, and the semi-aquatic behavior of modern beavers has evolved from a burrowing ecosystem. Beavers evolved from burrowing to swimming in water.”

“Fossils of other organisms found at the site where Microtheriomys actiulaquaticus was discovered indicate it was once a water environment, providing further evidence supporting the hypothesis.”

Analysis of beaver body size over the past 34 million years shows that the evolutionary process of beavers follows a rule known as Cope’s Rule, which states that organisms in evolutionary lineages tend to increase in size over time.

Castoroides, or the giant beaver, is a gigantic beaver species, the size of a bear, that lived in North America during the Pleistocene epoch. Two species are currently recognized, C. dilophidus in the southeastern United States and C. ohioensis in the remainder of its range. C. leiseyorum was previously described from the Irvingtonian of Florida but is now considered an invalid name. All specimens previously described as C. leiseyorum are now considered to belong to C. dilophidus.

The largest beaver species ever recorded by paleontologists is Castor, which are extinct giant beavers the size of a black bear that lived in North America around 12,000 years ago.

Before extinction, this beaver species was highly successful. Its fossils have been found at numerous sites stretching from Florida to Alaska and even Yukon. They weighed up to about 100 kg.

Compared to modern beavers, the giant beavers did not have a paddle-shaped tail; instead, they had a longer, smaller tail. Their incisors were also very large, more curved, and not sharp.

This beaver species suddenly went extinct at the same time as many other Ice Age animals, including the woolly mammoth. There is very little certain information about the interaction between humans and Castoroides. However, remains of Castoroides have been found alongside human artifacts in Sheriden Cave. There are numerous scientific theories surrounding the extinction of Castoroides, and to date, scientists have not pinpointed the exact cause of this species’ demise.

Scientists indicate that they thrived in warm and humid climates, found in ancient wetlands. They did not have the habit of “cutting trees” or eating vegetation like modern beavers, but rather consumed aquatic plants.

Feeding on aquatic plants made them dependent on wetland areas for survival and thus vulnerable to climate change.