In the natural world, the act of naming and addressing one another by specific names has long been considered a privilege of humankind—intelligent beings capable of using language as a sharp tool to navigate social relationships.

It is unclear when our ancestors began to evolve this capability. However, it is likely that it all began around a campfire in Africa over a million years ago, when an early Homo erectus conceived the idea of calling his friend “UGrraaa” instead of using generic terms like “You there,” “Buddy,” or “The long-haired guy with the stick.”

Naming allows humans to save time, avoid confusion in task distribution, and most importantly, it creates what is known as “personal identity”—a profound concept that only humans are intelligent enough to devise.

A name can carry a story, a history, and even the social status of the individual. It becomes a symbol, a reminder that they are not just part of a group but also a distinct entity with unique thoughts, feelings, and aspirations.

With all this complexity in mind, humans have long been confident that they are the only species on the planet capable of naming and addressing each other by personal names. Even our closest relatives, the chimpanzees, do not possess this ability. They remain at a lower developmental stage, with each chimp needing to recognize others by their faces, voices, and gestures.

Yet, in a recent study, scientists made a surprising discovery: Marmosets, a small primate species also known as “squirrel monkeys” in South America, can indeed name each other. These monkeys use specific calls, referred to as “phee-calls,” to address one another.

Scientists believe that this is a behavior with “high cognitive” functionality, never before observed in non-human primates.

Marmosets, a small primate species known as squirrel monkeys in South America, have the ability to name each other.

The new research was conducted by scientists from the Hebrew University in Israel, who performed a very simple experiment to confirm the linguistic abilities of a group of 10 Marmosets.

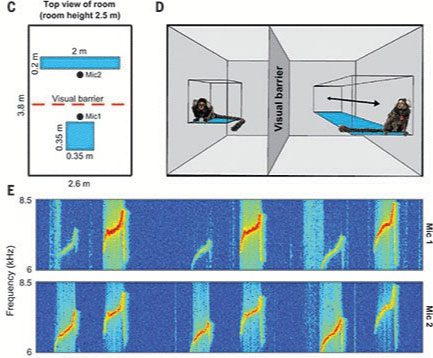

“We placed each pair of Marmosets in the same room and blocked their view of each other. By doing this, the pair of monkeys could only communicate with each other, and they did so quite naturally,” said Dr. David Omer, the lead author of the study from the Safra Brain Science Center at the Hebrew University.

Dr. Omer’s team recorded all conversations between the pairs of Marmosets, totaling 10 individuals from 3 different families. The conversations were recorded and analyzed using computer programs capable of identifying common “words” used frequently by the monkeys.

By combining this with the context in which these words were used, Dr. Omer could confirm that these were indeed the “names” that the Marmosets assigned to one another.

Experiment model and the Phee-calls sound recorded and analyzed by scientists.

The calls of Marmosets are often referred to as “phee-calls” because they commonly produce sounds resembling a whistle “phiiii phiii.” The tones within this range are modified by Marmosets to name each other. Therefore, you can imagine one Marmoset calling another “Phi,” and another “Phi Phi,” quite endearing names.

“Previously, we thought that the calls of non-human primates were a genetically determined form of communication lacking flexibility,” Dr. Omer stated. “But now we have seen that Marmosets are capable of creating a highly diverse vocabulary.”

According to the study, Marmosets rely heavily on visual cues but also demonstrate a “complex chain of social calls”—of which “phee calls” are only one form of their language. These calls are typically used for communication when they cannot see each other.

By calling each other by personal names, Dr. Omer observed that Marmosets could distinguish between communications directed at them and those that were not relevant to them. For instance, when one monkey calls “Phi,” it speaks to Phi while the monkey called “Phi Phi” does not engage in the dialogue.

Previously, these calls were understood as a method of “self-location,” Dr. Omer noted—essentially a way to announce their location to others. However, the new research indicates that these “phee calls” are actually “labeling” signals akin to specific names of the Marmosets.

“This is the first time we have observed this in non-human primates,” the researchers wrote in their report.

Dr. David Omer, lead author of the study from the Safra Brain Science Center at the Hebrew University.

Analysis of hundreds of recordings from the experiments also revealed that Marmosets within the same group use “similar sound labels to call different individuals” and possess “similar sound characteristics to encode their names.” This can be likened to human dialects.

Monkeys that are not genetically related but can use the same “dialect” indicate this is a learned behavior rather than a genetic trait. It is akin to a person from the North who is born and raised in the South speaking with a Southern accent instead of the Northern accent of their parents.

“We can be sure that a learning process has taken place here. Marmosets can name family members—and this is not due to genetics,” Dr. Omer affirmed.

The study serves as evidence providing new insights into how language and social communication developed in the past.

“Until now, we thought that human language was a ‘Big Bang’ phenomenon arising from nothing and only occurring in humans—this is completely contrary to evolutionary theory.

This discovery, along with other findings, suggests for the first time that there were developments of pre-linguistic communication in non-human primates, and we may find further evidence indicating this is an evolutionary process,” Dr. Omer said.

The call “Phi Phi” of Marmosets in the wild.

Earlier this year, another study also found that African elephants can address each other with personalized calls, similar to the personal names used by humans. Additionally, the behavior of calling each other by names has also been recorded in dolphins. However, among primates, naming has never been observed, except in humans.

Now, this new finding will add Marmosets to the list of “sitting at the same table” with the most linguistically advanced animals on the planet. Somewhere amidst the lush green canopies of South America, Marmosets may currently be holding lively “family gatherings.”

In these gatherings, they might point each other out and ask questions like: “Why hasn’t Phi Phi shown up yet?”, “Phi Phi is always late,” “Who called Phi Phi over?”.