X-rays have significantly contributed to modern medicine, but the early experiments to discover them came at the cost of human lives.

In December 1895, German physicist Wilhelm Roentgen submitted a preliminary report to the journal of the Würzburg Physiological and Medical Society, describing the discovery of “a new type of ray.” This previously undiscovered radiation, which he named X-rays, could penetrate solid objects like wooden blocks and thick books, even human flesh, creating shadows of bones. Within weeks, the news spread worldwide, igniting countless debates in journals regarding this new discovery and its potential applications in biomedical science.

The damaging effects of Roentgen rays on living tissue were first hypothesized by Italian physicist Angelo Battelli as early as March 1896. Many other engineers raised concerns, but the potential of X-rays was so great that some scientists were willing to set aside their worries to explore this groundbreaking discovery. One of the first to pay the price for this discovery was Clarence Madison Dally.

Dally was born in Woodbridge, New Jersey, in 1865. His father was a glassblower at the Edison Lamp Works in nearby Harrison, which specialized in producing light bulbs. At the age of 17, he enlisted in the Navy, serving for six years before being discharged. Upon returning home to Woodbridge in 1888, Dally began working alongside his father and three brothers at Edison Lamp Works.

Edison looking through a fluorescent screen to observe X-rays on Clarence Madison Dally’s hand. (Photo: Wellcome Images).

The first X-ray photograph taken by Wilhelm Conrad Roentgen.

When Roentgen announced the discovery of X-rays in 1895, Thomas Edison quickly recognized their importance and believed they could be used to improve incandescent lamps. Edison was particularly interested in one of Roentgen’s experiments, where the researcher coated a glass screen with barium platinocyanide and shone X-rays onto it. The crystals would glow in the dark when exposed to X-rays. Edison was convinced that if he could find the right fluorescent material, he could make the screen glow brightly enough to illuminate an entire room.

It is known that because he was captivated by the early X-ray images of another scientist, Edison decided to research this new technology. He needed a hand for his experiments but could not use his own as he had to observe and work with both hands.

Thus, his assistant, Clarence Dally—who was very enthusiastic about X-ray technology—was always ready to become Edison’s test subject. According to documented accounts, while Dally always wanted to experiment with the strongest X-ray tubes, Edison attempted to use weaker tubes.

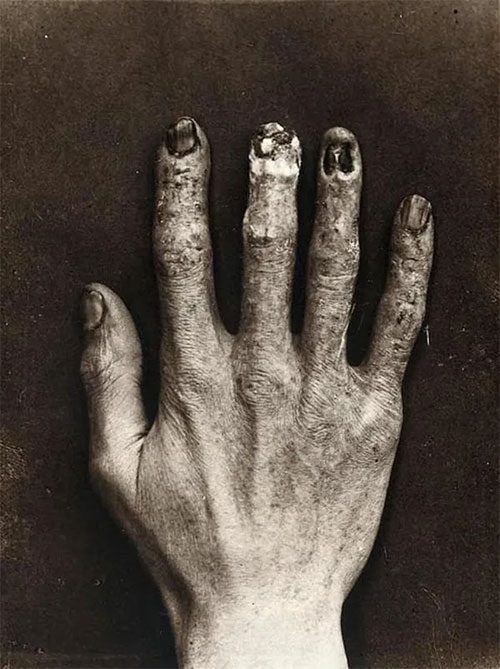

As a result, Dally’s left hand, after numerous exposures to the radiation, was constantly covered in burns. However, curiosity about new discoveries always captivates people. Other assistants of Edison reported that whenever they saw Dally, they noticed his hand was actively involved in experiments. A few years later, Edison invented the first fluorescent lamp that allowed viewing bones beneath the skin.

Despite his worsening condition, Dally remained eager to contribute to science. At only 35 years old, he had lost most of his hair and looked older than his peers. His left hand was always swollen and painful, with sores spreading to his arm and face. Edison documented his assistant’s condition in his journal every day.

Dally’s left hand after multiple exposures to radiation, always covered in burns.

Due to the weakness of his left hand, Dally used his stronger right hand to continue his experiments. However, shortly after, his right hand also became swollen and painful, forcing him to soak it in cold water every night to relieve the pain and to be able to sleep. A few years later, doctors performed surgery to graft skin from Dally’s leg onto his left hand, which was gradually deteriorating, but the results were not promising.

According to modern scientific findings, Dally developed skin cancer due to radiation exposure. He had to have his left hand amputated, and a few months later, he underwent amputation of four fingers on his right hand. In 1903, he had his right hand amputated. A year later, he passed away at the age of 39, eight years after his first exposure to X-rays. In his final years, despite having lost his hands and no longer working in the laboratory, Dally expressed to Edison that he could assist with scientific experiments for the rest of his life.

After his assistant’s death, Edison experienced significant psychological trauma.

“Don’t talk to me about X-rays,” he said.

“I fear them.”