The first taxis on the streets of New York (USA) did not run on gasoline but on electricity – “the cars of the future turned out to come from the past.”

The bustling streets of 19th century Manhattan had a problem with horses. It is estimated that around 150,000 horses roamed the city, each producing 22 pounds (nearly 10 kg) of waste every day.

The inauguration of New York City’s motorized taxi service on March 27, 1897, promised a cleaner solution: The first taxis did not run on gasoline but on electricity. It turns out that the car of the future actually came from the past.

Electrobat – one of the world’s first fully electric vehicles, highly favored by the elite in Manhattan, New York, in the late 19th century. (Source: National Geographic)

The 1890s

With the idea of electric vehicles cruising around New York in the 1890s, battery-powered cars sold better than internal combustion engine vehicles at the dawn of the automobile era. Electric cars were quiet, clean, and easy to drive.

“Back then, you were lucky if a gasoline car started in the morning” – Dan Albert, author of “Are We There Yet? The American Automobile Past, Present, and Driverless,” said. “It was noisy, polluting, and clunky, while an electric car just needed to be turned on with a flip of a switch.”

In the 19th century, as electricity started to be used practically, it seemed capable of overcoming all challenges. “If you asked people on the street what would happen, they would say electricity was ‘a magical force’” – automotive historian David A. Kirsch stated.

“We harness electricity to create light. We use electricity to provide the pulling power for vehicles. Electricity is ‘spreading’ everywhere, and now it takes us everywhere.”

The Pioneering Electrobat

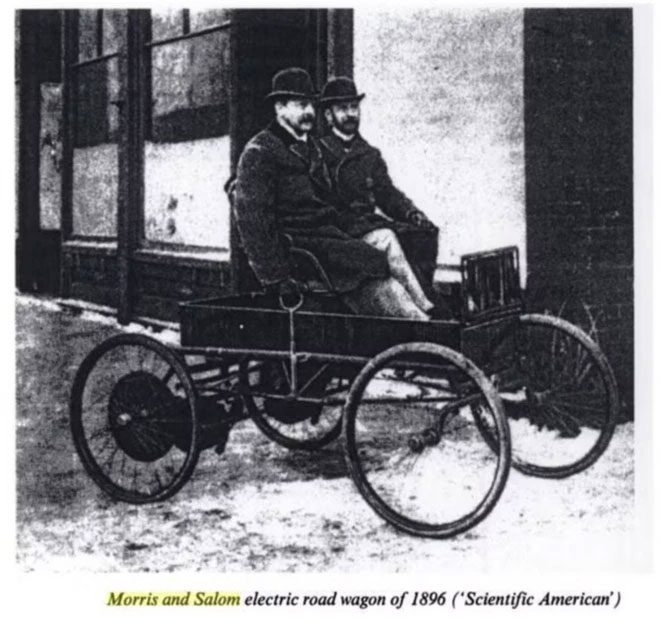

While Nikola Tesla was the “only Tesla” making headlines, Electrobat emerged as the first commercially successful electric vehicle. Built by Philadelphia engineers Henry Morris and Pedro Salom in 1894, this 2,500-pound (over 1.1-ton) vehicle was powered by lead-acid batteries. It reached a maximum speed of 15 miles per hour (24 km/h) and could travel up to 25 miles (over 40 km) on a single charge.

Moreover, these two engineers devised an intelligent battery swapping system inside an old Broadway skating rink to keep the vehicle operational continuously.

Working with the efficiency of a NASCAR pit crew, the staff operated the vehicle using elevators and hydraulics like a crane, “yanking” out the depleted 1,000-pound (453 kg) batteries and replacing them with fresh ones.

This process took only three minutes. Kirsch noted: “It was much faster than swapping a team of horses and probably as quick as filling a gas tank today.”

The Manhattan taxi service of the “duo” of engineers quickly became popular, especially among the elite of society. Instead of selling the vehicles, Morris and Salom chose to rent them on a monthly or per-trip basis through their venture, Electric Wagon & Carriage Company.

The taxi fleet experienced significant growth, from just about a dozen cars in 1897 to over 100 vehicles by 1899. Electrobat proved to be the ideal “street car” with its quick acceleration and quiet operation.

However, its speed and silence posed unforeseen challenges.

An electric vehicle from Morris and Salom in 1896. (Source: HotCars).

In May 1899, the press reported that taxi driver Jacob German became the first driver to be arrested for speeding after zooming down Lexington Avenue at 12 miles per hour (19 km/h).

Weeks later, an electric taxi fatally struck real estate broker Henry Bliss as he stepped off a streetcar in the Upper West Side: The first pedestrian to be killed by an automobile never heard the Electrobat approaching.

The “Bubble Bursts”

Morris and Salom found new support from wealthy investors, notably New York financier William Whitney – famous for his success in electrifying the city’s streetcars.

Under Whitney’s leadership, the company merged with battery and electric railway manufacturers to create an integrated national electric transportation network.

The Electric Vehicle Company quickly expanded its taxi operations to major cities like Philadelphia, Chicago, and Boston, eventually becoming the largest automobile manufacturer in the country.

However, the rapid expansion of the company proved unsustainable. Operations outside New York were poorly managed, and investors felt deceived when a New York Herald investigation at the end of 1899 revealed that the company had committed fraud to secure a loan. The company’s stock plummeted, and the business nearly went bankrupt by 1902.

The Collapse

The downfall of the Electric Vehicle Company sent shockwaves through the investment community and cast a shadow over the future of electric vehicles.

Albert stated: “What ‘killed’ the company wasn’t really the idea, technology, or business model – but the deceit of the traders behind it.”

A catastrophic fire destroyed a significant portion of the fleet. Along with the economic turmoil of the 1907 crisis, this fire dealt a “final blow” to electric taxis in New York just as gasoline-powered vehicles began to gain traction in the market.

That same year, local businessman Harry Allen introduced a taxi service with 65 gasoline-powered taxis imported from France. Within a year, his fleet grew to 700 vehicles.

The internal combustion engine propelled the next century of American transportation, but battery-powered energy is gradually making a comeback after a long journey. When 25 fully electric taxis began operating on the streets of New York in 2022, the car of the future emerged – once again.