On the Grasslands of Ethiopia, Large Troops of Gelada Monkeys May Be in the Process of Domesticating Wolves.

Geladas are a unique species of monkey in many ways; they inhabit the mountains and grasslands of Ethiopia and are known for their very special diet. Unlike other monkey species, geladas primarily eat grass. Almost their entire diet consists of the plants they graze from the ground.

The gelada monkey (Theropithecus gelada) closely resembles a baboon. This primate is known to live in tightly-knit family groups, but they can also exist in large herds of up to hundreds of individuals in an extremely peaceful manner – a relatively rare occurrence in the wilds of Africa.

Essentially, they are the only primate species that lives almost entirely on grass, a characteristic typically seen in ungulates like deer and cattle.

However, perhaps the most interesting trait of the gelada monkey is not what we just mentioned – some evidence suggests that, like humans did thousands of years ago, this primate may have started to develop a cooperative relationship with Ethiopian wolves. Some scientists speculate that their interactions could be the beginning of a domestication process.

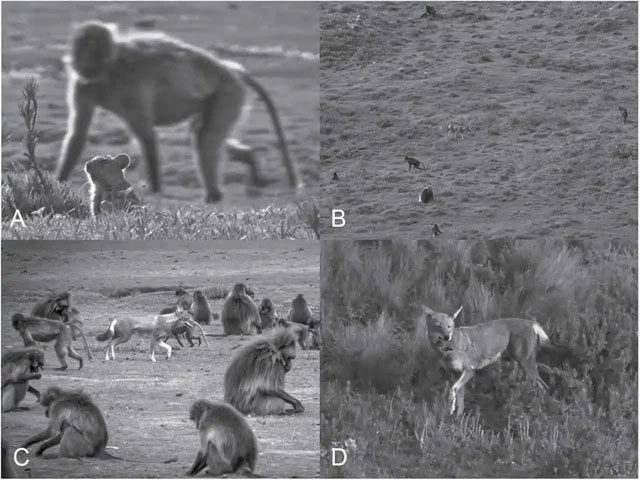

On the grasslands of Ethiopia, scientists were astonished to find a remarkable example of interspecies cooperation. Ethiopian wolves were observed wandering among gelada monkeys, and the monkeys seemed familiar with the wolves’ presence, showing no fear of them. Conversely, the wolves displayed no desire to attack the geladas; instead, they preferred to linger around the monkey herds as it helped them catch more prey, particularly rodents. Some researchers suggest this unusual relationship bears many similarities to the domestication of ancient dogs or cats by humans.

How Humans Domesticated Wolves

While most people know that dogs were domesticated from wolves, there is still much debate about when and why this occurred. However, scientists agree that this process began thousands of years ago, though they remain uncertain as to whether it started in Europe, Asia, or in both regions simultaneously.

The process of human domestication of wolves began thousands of years ago.

The process of human domestication of wolves began thousands of years ago.

Nevertheless, scientists have a compelling idea about how this domestication process may have occurred. It is believed that humans, after engaging in large game hunts – such as a woolly mammoth hunt – left behind many bones and scraps of meat. Consequently, wolf populations caught the scent of the meat and instinctively approached human hunting areas to scavenge bones and scraps. Over time, some wolf populations became accustomed to humans, grew less aggressive, and gradually won human affection, leading to active domestication.

Importantly, it is essential to understand that this domestication process was beneficial for both species involved. According to the American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (ASPCA), wolves gained easy meals by being near humans, and in return, they could serve as guard dogs, alerting humans to potential dangers.

Evidence That Gelada Monkeys Are Domesticating Wolves

While the monkeys gather in massive herds, grazing for hours, the Ethiopian wolves (Canis simensis) blend in with the gelada monkeys. Typically, wolves move in a zig-zag pattern, sprinting when they feel prey is within reach. However, when near the gelada troop, the wolves wander casually, being careful not to startle the entire herd.

If you think that humans are the only ones capable of domesticating animals, then you might have to rethink that now.

Research shows that gelada monkeys may also have a semi-cooperative relationship with wolves – in this case, with Ethiopian wolves. Scientists observing gelada monkeys discovered that when the monkeys gather in groups to forage for food, wolves sometimes dash through their midst. This is not intended to frighten the monkeys – the wolves are not stalking the primates. According to Insider, the wolves have no intention of attacking the monkey troop; instead, they are interested in the surrounding rodents.

After monitoring the Ethiopian wolves for 17 days, researchers found that wolves hunting rodents within the gelada troop had a success rate of 67%, while their usual success rate when hunting alone was only 25%. These findings were published in the Journal of Mammalogy.

“For Ethiopian wolves, establishing proximity to gelada monkeys is an adaptive strategy to enhance foraging success,” the study authors wrote.

Currently, it is unclear what makes wolves more successful at hunting when in the presence of gelada monkeys. However, there is speculation that the monkeys may be driving rodents out of their burrows as they graze continuously, but this is merely an unverified hypothesis at this stage. Additionally, the monkeys might be providing cover for the wolves, distracting the rodents from the lurking predators.

Researchers at Dartmouth College have observed interactions between species for a new study. They concluded that Ethiopian wolves show little interest in hunting gelada monkeys for food, although they do not hesitate to hunt sheep and goat kids. The monkeys seem to be aware of this, as they do not feel threatened by the presence of the wolves.

Sometimes, a few wolves may attack juvenile monkeys, but other monkeys in the troop quickly retaliate against the wolf, forcing it to release the young.

Once the wolf is driven away, it will not be allowed to return to the troop again. Consequently, other wolves seem to understand this behavior well and resist the temptation to hunt gelada monkeys to continue hunting the surrounding rodents.

Currently, the monkeys do not appear to gain any benefits from the presence of the wolves, and without a two-way value exchange between the two species, domestication cannot occur.

However, when comparing this to the hypothesis of human domestication of wolves, we can see many similarities – in the early stages, wolves approached humans solely for their own benefit. At that time, humans gained no advantages from them and could even be attacked by wolves. But over time, humans began to actively provide food for wolves, gradually transforming them into “tools” to help detect threats at night and find prey while hunting.

Could the same scenario occur on the grasslands of Ethiopia? Over thousands of years, will the geladas see wolves as pets? Only future research will truly reveal what the relationship between geladas and wolves will yield for the monkeys. Similarly, time will tell if a true domestication relationship between these species will ever develop.