Latest Research Reveals Gut Bacteria May Influence Human Appetite

When we plan the foods we want to eat daily, our decisions may not stem from “commands from the brain.” A recent experiment conducted on mice at the University of Pittsburgh, USA, has shown that the gut bacteria of animals can influence their dietary choices, with these bacteria producing substances that make the animals crave certain types of food.

Kevin Kohl, an associate professor in the Department of Biology at the University of Pittsburgh, stated: “We all have some cravings – for salad or for meat, and the new research shows that different gut bacteria in animals can determine their food preferences.”

Although scientists have speculated for decades about whether gut bacteria influence our food preferences, it wasn’t until recently that this idea was tested on mammals. Kevin Kohl and his colleague Brian Trevelline conducted a special experiment in which 30 germ-free mice were injected with a mixture of gut bacteria from three different wild mouse groups with varying diets.

The gut microbiome is a complex community of microorganisms living in the digestive tracts of humans and other animals, including insects. The gut metagenome is the sum of all the genomes of the gut microbiome. The gut is one of the habitats where human microorganisms reside.

Kevin discovered that each group of mice in the experiment exhibited different preferences for nutrient-rich foods, indicating that the injected gut bacteria had altered their previous eating habits. These findings were recently published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America.

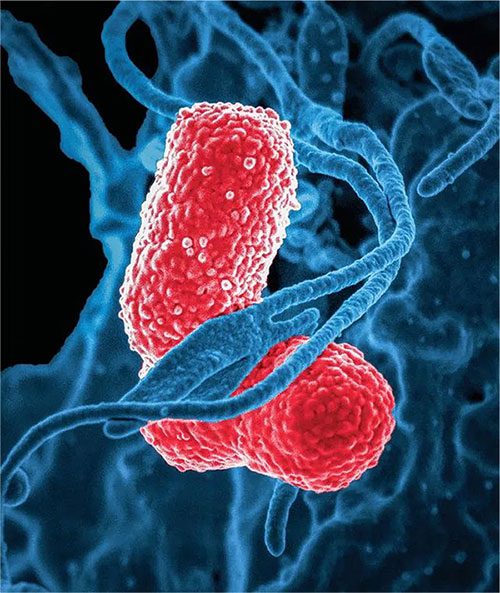

While the idea that the microbiome influences human behavior may seem far-fetched, scientists have taken a rigorous scientific approach. In fact, the human gut and brain continuously communicate with each other, with certain molecules acting as “mediators.” Digestive byproducts in the gut can signal whether a person has eaten enough or needs a specific nutrient. At the same time, gut bacteria can produce some “mediating molecules” that may hijack the original communication pathways between the gut and brain, thus altering the meaning of the messages.

In humans, the gut microbiome contains the largest number of bacteria and the greatest variety of species compared to other areas of the body. The gut microbiome is established within one to two years after a person is born, at which point the intestinal epithelium and the mucosal barrier it secretes have developed mechanisms to tolerate and even support the gut flora while providing a barrier against pathogens.

Typically, for those who have consumed turkey, there will be a very familiar signaling molecule in their body – tryptophan. Tryptophan is an essential amino acid found abundantly in turkey meat and is also produced by gut bacteria. Brian Trevelline noted: “When tryptophan enters the brain, it is converted into serotonin, a crucial signal for post-meal satisfaction, and ultimately it is metabolized into melatonin, which makes people feel drowsy.”

In this latest research, Brian and Kevin demonstrated that mice with different gut microbiomes had varying concentrations of tryptophan in their blood, and they even chose different types of food. They also found that the higher the concentration of tryptophan in the blood, the more gut bacteria there were.

The composition of the human gut microbiome changes over time, as dietary habits shift and as overall health changes. A systematic review from 2016 examined preclinical and small human trials conducted with various commercially available probiotic strains and identified the bacteria with the most potential benefits for certain central nervous system disorders.

Brian Trevelline emphasized that this is compelling evidence and concluded that tryptophan is just one clue in a complex network of chemical communication. There may be dozens of signals influencing daily eating behavior. Tryptophan produced by microorganisms may be just one factor, but it is a reasonable explanation that gut bacteria can alter our dietary choices. While scientists have strived to establish and refine this theory over the years, this is just one of the few rigorous experiments to demonstrate the connection between the gut and the brain.

Kevin remarked: “There are many factors that determine people’s dietary choices, and what they ate the day before may be more significant than the gut microbiome.”

He also pointed out that this could merely be a behavior influenced by microorganisms that we are unaware of. This is a new area of exploration, and there is still much knowledge to uncover.