The era of dental offices and operating rooms as true torture chambers is over! Since the 19th century, humanity has finally discovered ways to alleviate pain.

Suffer or Die

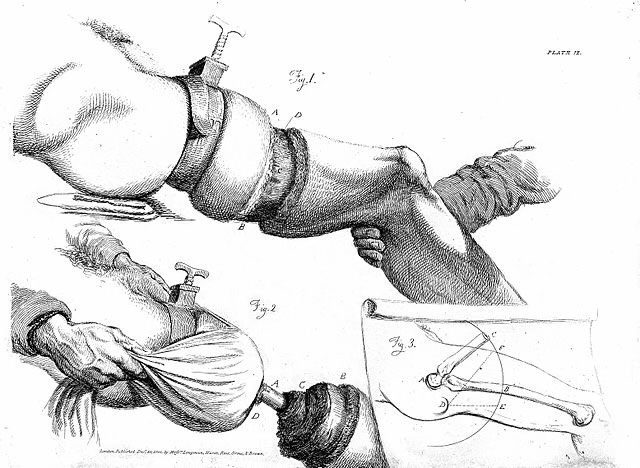

For thousands of years, tooth extractors, barbers, and surgeons have known how to cut and remove abscesses and any body parts affected by gangrene or other wounds. The only solution to lessen the pain was to act quickly. Many could amputate a patient’s arm or leg in just a few seconds! It wasn’t until the 16th century that the renowned surgeon Ambroise Paré suggested using a mixture of opium and strong alcohol to relieve pain and to sew up wounds rather than burning them with a red-hot iron, which was exceedingly brutal.

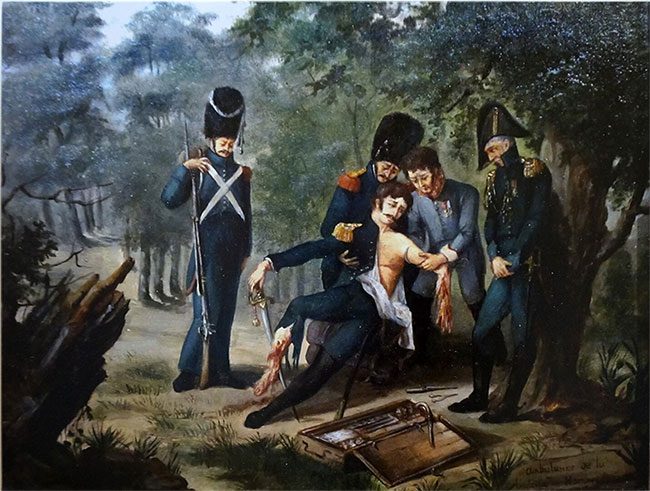

During the retreat from Russia, Dominique Jean Larrey, the surgeon for Emperor Napoleon, noticed that the cold lessened the pain for patients undergoing surgery and that this method could be used to amputate gangrenous limbs. However, there was no way to prevent the screams of the unfortunate patients. Therefore, in hospitals, operating rooms were placed far from treatment areas to avoid the horrifying cries disturbing other patients and visitors.

Scene of Dominique Jean Larrey, surgeon for Emperor Napoleon, amputating a limb “in emergency” on the battlefield of Hanau.

From British Scientists…

In 1789, John Priestley isolated oxygen and obtained a peculiar gas known as nitrous oxide (laughing gas). In 1794, Humphry Davy, a 16-year-old apprentice, noticed that Priestley’s gas lessened toothache. He suggested using it to combat pain, especially during surgery, but those close to him paid little heed to that “devilish” gas.

In 1818, Michael Faraday, already famous for his inventions in electricity, discovered the anesthetic effects of ether, a gas related to nitrous oxide. However, this discovery was not exploited. After numerous attempts to use ether as an anesthetic and operating on some animals, in 1824, Dr. Henry Hill Hickman presented his findings to the British Medical Society, but to no avail. In 1828, he approached the French Academy of Medicine, but only Larrey supported him.

…To American Dentists

During this time, the fame of these inventions crossed the Atlantic and became a major topic of gossip. On October 10, 1844, Horace Wells, a dentist in Hartford (the capital of Connecticut, USA), laughed heartily after inhaling laughing gas accidentally released by a friend. Surprisingly, the next day, he became unconscious and extracted a tooth without feeling anything. He repeated this experiment with several patients and immediately informed renowned surgeon J.C. Warren in Boston about the miraculous method he had just discovered.

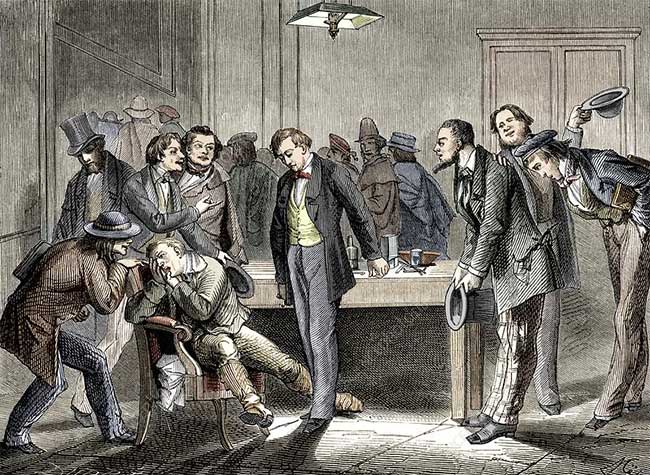

But it was complicated! Because he had not mastered the technique, when he tried to present his invention again, a fat, drunken volunteer who acted as his test subject messed things up. He woke up screaming, and Wells had to escape due to the uproar. However, another dentist, William Green Morton, who witnessed the entire incident, understood that Wells had miscalculated the dosage.

Wells using laughing gas for a tooth extraction in public.

No More Pain

Following the guidance of a friend, chemist Charles Thomas Jackson, Morton experimented multiple times with pure sulfuric ether. Jackson then persuaded Warren to perform the first surgery under general anesthesia using a custom-made gas inhaler. This time, it was a resounding success. Warren disseminated this method throughout the United States and Europe.

Scene of the first anesthesia in Boston hospital. Morton holding the gas inhaler.

This great discovery was a blessing for patients but ruined the inventor’s career. He spent the rest of his life disputing patent rights. For in 1842, Carl Long, a doctor in the South, had used ether in minor surgeries without ever thinking about reporting it to the scientific community.

Even the Queen

Ether is an effective anesthetic, but when inhaled, it can cause severe coughing and sometimes lead to death. Therefore, scientists experimented with various formulations. In 1847, to alleviate the pain of childbirth, James Young Simpson, a professor of obstetrics in Edinburgh, used chloroform, which had just been demonstrated to have anesthetic properties by Pierre Flourens, a French scientist.

On April 7, 1853, Dr. John Snow popularized this method by administering it to Queen Victoria during her childbirth. This product quickly replaced ether in surgical procedures, but today it has been abandoned in favor of the less toxic nitrous oxide.

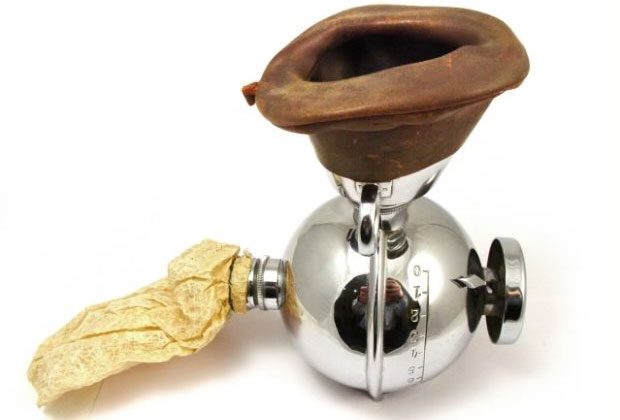

In 1908, Ombredanne perfected a new machine that allowed for precise control of the anesthesia process; the gas released could be adjusted as needed throughout the surgery. The waste gas was expelled through a valve system rather than being mixed with the inhaled gas, and a device was created to monitor the patient’s breathing.

Ombredanne’s machine.

From Inhaling Gas to Intravenous Injection

In 1872, anesthesia was first administered through intravenous injection using the syringes perfected by the French genius Charles Gabriel Patraz in 1852. It wasn’t until the 20th century that this method became widely adopted, alongside the most reliable formulation, Pentothal, which was introduced in 1934. By managing anesthesia with morphine, which somewhat alleviated pain, doctors could limit the dosage of painkillers.

On January 23, 1942, Griffith and Johnson, two surgeons in Montreal (Canada), added curare (a toxic resin used by indigenous people on arrow tips) to the anesthetic mixture to paralyze muscles and prevent the involuntary movements of patients that caused many inconveniences for surgeons. However, it posed a challenge since if the muscles stopped working, breathing could also cease. This issue was resolved by the invention of a tracheal tube that ensured the supply of artificial oxygen to the patient.

Demand oxygen mask.

Since then, anesthesia techniques have continuously improved. They have significantly contributed to the great advancements in surgery. Speed has given way to sophistication and precision as surgeons can operate on patients who are peacefully asleep like logs.