It is not by chance that Japan has become one of the cleanest countries in the world; cleanliness has long been intertwined with a part of Japanese belief.

“Take everything out of your room and clean it thoroughly.” “You should only keep what is necessary; do not hesitate to discard items that are no longer usable.” When reading these quotes, you might immediately think of one of the best-selling books by Marie Kondo.

Marie Kondo is regarded as a symbol of modern home organization.

She has authored numerous books related to cleaning, interior organization, and is behind countless unique cleaning methods, focusing on a minimalist lifestyle.

However, you may be surprised to learn that Zen master Shunryu Suzuki, the founder of the San Francisco Zen Center, was the one who wrote these principles back in 1970, well over a decade before Kondo was born. The tidy, minimalist lifestyle has long been an important aspect of Japanese belief.

The High Value Placed on Cleanliness by the Japanese

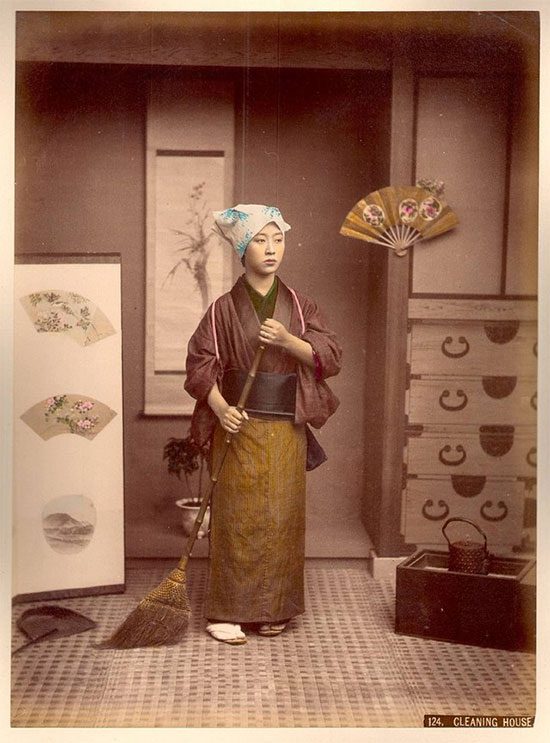

The Japanese elevate cleaning to the level of art.

From the very first moments of interaction, it is easy to recognize that the Japanese always strive to maintain a clean lifestyle as much as possible. Rear Admiral Matthew Perry of the United States Navy was astonished when he first saw the very clean and fresh port city of Shimoda in Japan in 1854.

In the book “Narrative of a Three Years Residence in Japan” published in 1863 by British diplomat Sir Rutherford Alcock, he did not hide his admiration and affection for the neatness and cleanliness of the Japanese. A few years later, American educator William Elliot Griffis praised their daily bathing habits and other sanitation practices.

In Japan, children from elementary school are required to participate in daily classroom cleaning activities. While schools do hire custodians to clean common areas, restrooms, and teachers’ lounges, today, maintaining classroom cleanliness is also the responsibility of the students. Each day after school, they divide into groups to take turns wiping desks, sweeping floors, and taking out the trash.

Transforming Cleaning into an Art Form

The Japanese value cleaning to the extent that they have turned it into an art form. The art of cleaning was recorded over a millennium ago in a book called Engishiki, specifically in the year 927 AD.

This handbook was compiled by the government to guide the cleaning practices of the Kyoto Imperial Palace. From the early stages of cleanliness culture, cleaning was not merely confined to the surrounding environment but also took on the form of a purification ritual, sweeping away misfortunes of the year to welcome a fresh start.

Cleaning also takes on the form of a purification ritual, driving away misfortunes.

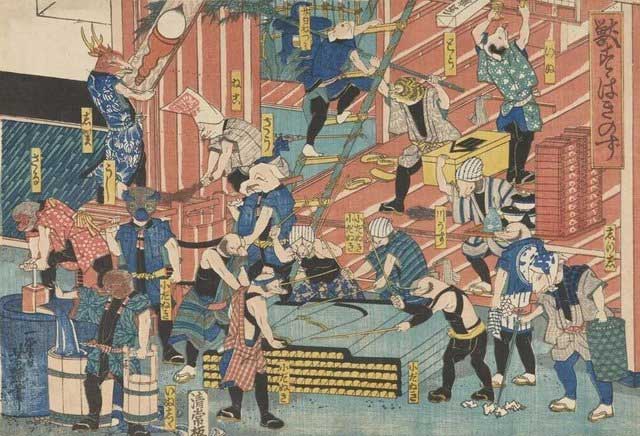

This spiritually influenced form of cleaning has been widely adopted by Buddhist temples and Shinto shrines since the 13th century, gradually spreading throughout the country, from which the ancient Japanese society began the Ohsoji festival – an occasion for people to tidy up their homes.

In the 17th century, most citizens, from samurai to commoners, regarded December as the month for thorough house cleaning, tidying up their ancestors’ altars to prepare for the arrival of the New Year deity, Toshigami.

The annual cleaning ritual known as Susu-harai.

Before being known as Ohsoji, the annual cleaning ritual was called Susu-harai, meaning sweeping away soot. In ancient times, the Japanese often used firewood for heating and candles for lighting when it got dark. As a result, much dirt accumulated on the walls and ceilings.

Today, people use special cloths and brooms to thoroughly remove dirt from their homes. Although it is housework, it is not seen as a tedious chore but rather as a means of warding off misfortune for the Japanese.

The Shinto belief includes a concept called Kegare (impurity), which is the opposite of purity; Kegare brings illness, which is why ancient Japanese sought to expel it. Many woodblock prints in Japan depict families celebrating after cleaning their homes thoroughly by joyfully tossing each other up.

Ancient Japanese also believed that plants, animals, natural phenomena, and even landscapes have souls, collectively referred to as kami. Followers see themselves as part of the natural and supernatural order by recognizing and honoring these sacred beings.

Kegare brings illness, which is why ancient Japanese sought to expel Kegare.

Kami is diverse. A particularly interesting example of Kami is Tsukumo-gami, the spirit of inanimate objects. Many may think that only Marie Kondo has the spiritual belief that kitchen utensils will “get angry” when forgotten in the cupboard, but in fact, this belief dates back to ancient times.

Followers of Kami pass down the belief that objects that exist for too long will harbor spirits, and if not treated well, they will become wrathful. Sentient objects, from straw sandals and old umbrellas to saddles and musical instruments, first appeared in Buddhist fables in the 16th century.

Images of these types of objects were mass-produced into printed books, which sold very well in the 18th century. Later, they became adorable mascots in Japanese culture (manga, anime).

In addition to Tsukumo-gami, we also have Bimbo-gami, the spirit representing the misfortunes suffered by the poor or those who do not clean their restrooms.

Is the Japanese Habit of Cleaning at Home Gradually Disappearing?

A recent survey by cleaning service provider Duskin revealed that only 52% of respondents thoroughly clean their homes annually. The primary reason is the changes in lifestyle and demographics of modern Japanese society (with more elderly than young people).

Going back to the 1970s and 1980s, it seemed that all of Japan closed down to enjoy and stop working to fully embrace the New Year holiday. At least from January 1 to January 3, or sometimes longer depending on the calendar, all offices closed, and employees flocked home to reunite with their families.

Even essential businesses such as grocery stores closed during the holidays, and the streets were quiet. Family members gathered together to enjoy Osechi: the traditional New Year meal of the Japanese. The meal symbolizes “prosperity” for the new year.

During the holidays, aside from eating, drinking, and watching TV broadcasts, there was nothing else to do. Nowadays, many large retail chains have expanded their operations, and many stores remain open during major holidays, even convenience stores in Japan never close. Moreover, over one-third of households in this country consist of single individuals.

Therefore, whether young or old, it is understandable that the habit of cleaning at the end of the year is gradually fading away. However, in the midst of adversity, there is opportunity; the pandemic seems to have reversed this trend, as Covid-19 has highlighted the importance of hygiene habits worldwide, and Japan is no exception.

The habit of cleaning at home at the end of the year is gradually disappearing.

Modern Japanese society always has measures and technologies to help people stay clean. Once you have lived here long enough, one day you will realize that you stop sneezing in public places, always use sanitizers in stores and offices, and learn to sort household waste into 10 different categories for easier recycling.