Centuries-Old Horse Skeletons from the Southwestern United States Help Rewrite a Colonial Legend.

Indigenous oral histories and archaeological evidence are reshaping the narrative of how horses arrived in the American West.

Horses lived in North America for millions of years but went extinct at the end of the last Ice Age, around 11,000 years ago.

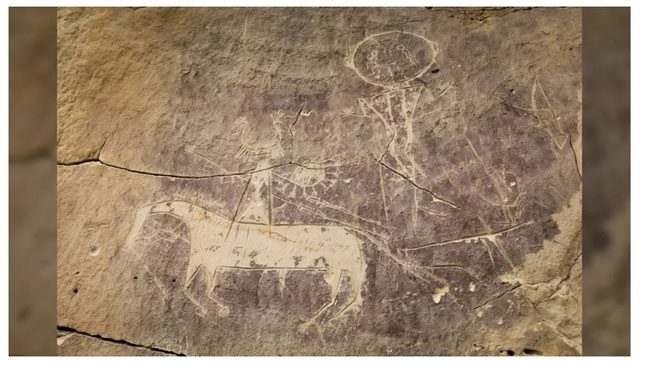

A gray-brown petroglyph depicting a horse and a rider.

When Europeans reintroduced horses to what is now the eastern United States in 1519, these hoofed mammals transformed the lifestyles of Indigenous peoples, rapidly altering food production, transportation, and warfare methods.

Spanish historical records indicate that horses spread throughout the Southwestern United States after the Pueblo Revolt of 1680, when Indigenous peoples forced Spanish settlers out of present-day New Mexico.

However, these records, generated a century after the uprising, do not align with the oral histories of the Comanche and Shoshone, who documented horse usage much earlier.

Using tools such as radiocarbon dating, ancient and modern DNA analysis, and isotopic analysis (isotopes are elements with different numbers of neutrons in their nuclei), a large and diverse group of researchers from 15 countries, including members of the Lakota, Comanche, and Pawnee nations, have determined that horses actually spread across the continent earlier and more rapidly than previously assumed.

Horses Used Over a Century Earlier

The research team discovered that two horse species – one from Paa’ko Pueblo, New Mexico, and another from American Falls, Idaho – date back to the early 1600s, decades before Spanish settlers arrived in the region.

Comparing DNA between historical horse skeletons and contemporary horse gene pools revealed that they are closely related to Spanish horse bloodlines. However, the horses studied were not directly imported from Europe.

By analyzing specific dental variations in several horse specimens, researchers found that these animals were locally bred and fed corn, a staple crop of Indigenous peoples.

Ultimately, through careful observation of the horse skeletons, researchers concluded that these animals were cared for and ridden. A healed fracture on the face of a foal from Blacks Fork, Wyoming, indicates it received veterinary care, while dental injuries and changes in the skull bones found at Kaw River, Kansas, may evidence riding practices in the mid-17th century.