Scientists explain the causes of the horrific disaster in Chamoli, India, in February, which claimed the lives of 204 people and destroyed hydropower infrastructure worth hundreds of millions of USD.

In February, a massive block of mud and ice, four times the length of the Empire State Building—one of the tallest skyscrapers in the world—plummeted at a terrifying speed down the valley in Chamoli district, northern India. This catastrophic flood resulted in 204 fatalities and completely destroyed two hydropower plants.

On June 14, the BBC cited a report from 50 international researchers detailing the causes and the entire event. This report draws conclusions based on various data sources, from satellite images to experimental observations.

Terrifying Weight

In the early hours of February 7, a rock mass at an altitude of 6 kilometers suddenly fell, breaking apart a glacier section over 500 meters wide and 180 meters thick atop Ronti Peak in the Indian Himalayas.

Upon striking the glacier, the rock shattered and melted the ice, creating a massive wall of water along with debris cascading down into the valley below—where the Rishiganaga and Tapovan hydropower plants were located, with hundreds of workers present.

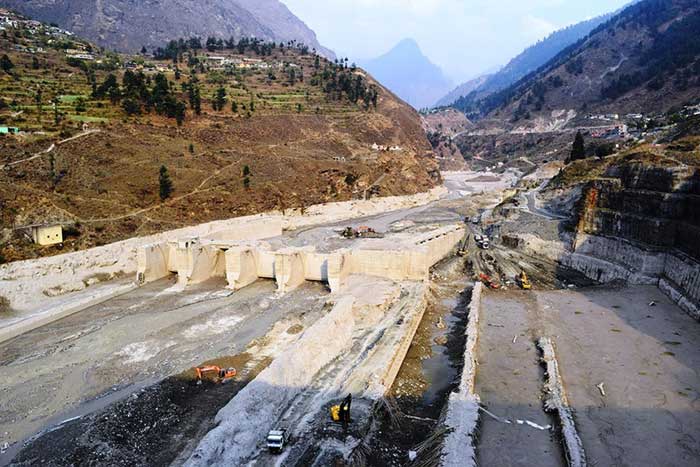

Tapovan Vishnugad hydropower plant destroyed after the horrific flood on February 7. (Photo: Insider).

Researchers calculated that nearly 27 million cubic meters of rock and ice fell into the valley—approximately 10 times the size of the Great Pyramid of Giza in Egypt, enough to cover over 1,600 football fields to a depth of 3 meters in mud and still have some left over.

When it fell into Ronti Gad valley, this ice block released energy equivalent to 15 atomic bombs dropped on Hiroshima. “The initial composition of the avalanche was about 20% ice and 80% rock. With that structure, combined with a drop of nearly 2 kilometers, it generated enough heat and friction to completely melt the ice (causing a flood to pour down into the valley),” explained Dr. Dan Shugar from the University of Calgary, Canada, the lead researcher.

Upon impact, the ice block immediately shattered, scattering debris within a 10-meter radius, while the explosive force flattened 20 hectares of nearby forest.

At the time it swept through the Rishiganga hydropower plant, the flow was moving at 90 km/h—equivalent to the speed of a fast-moving car. Even after traveling 10 kilometers to the Tapovan plant area, the flow still moved at approximately 57 km/h, resulting in the deaths of 204 people present at both plants.

Need for Reevaluation

At that time, there were several speculations that most of the water in the flow could have come from a glacial lake that had burst in the Himalayas. However, the research team dismissed this possibility. Many speculated that climate change was the cause of the disaster. The research team concluded that global warming was not considered a cause of this event. However, their viewpoint emphasized that the frequency of rock fractures in the Himalayas is increasing due to rising temperatures.

“Determining the specific cause of this disaster is very difficult,” said Professor Jeffrey Kargel from the Planetary Science Institute in Arizona, USA, a co-author of the study. “According to data from archival satellite storage, this ice mass began showing signs of slipping four years ago. Unfortunately, no one noticed this.”

Rescue operations taking place at the two plants. (Photo: Down To Earth).

The question arises as to what significance this research will hold for those living and working in the high-altitude region of Uttarakhand.

Kavita Upadhyay—a water policy expert and Indian journalist writing about the natural environment and hydropower in the area—asserts that careful consideration is necessary when constructing infrastructure in areas vulnerable to landslides, floods, and earthquakes.

“This is not the first time that power plants have been destroyed,” she said. “In the floods of 2012, 2013, and 2016, they suffered severe damage. Therefore, the question arises whether to continue placing plants in such a fragile area. At the very least, they should install disaster warning systems at the plants or in this region.”

According to Insider, a warning system—comprising seismic sensors to monitor signs of earthquakes or landslides—could alert residents 6 to 10 minutes before a flood arrives, allowing them to seek shelter.

“The Chamoli disaster once again shows that humans are underestimating the threat posed by installing infrastructure in high mountain areas,” agreed co-author of the study, Professor Dave Petley from the University of Sheffield, UK, with the Indian journalist’s viewpoint.

According to him, if humanity does not reevaluate the threat, it is highly likely that in the future, there will be a heavy price to pay in terms of human lives, economic, social, and environmental impacts related to these activities. The research on Insider indicates that: “it is only a matter of time before a similar event occurs somewhere in the Himalayas.”