Inventor Granville T. Woods once triumphed over Edison in a patent lawsuit concerning the induction telegraph system, which revolutionized the transportation industry.

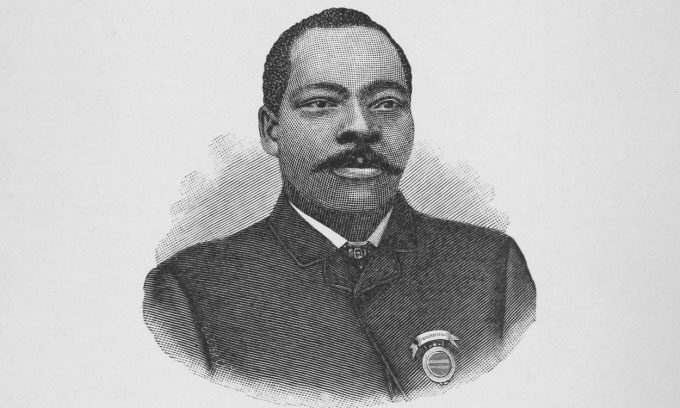

Granville T. Woods was the most successful Black inventor of the late 19th century. Woods is considered the first African American electrical and mechanical engineer after the American Civil War (1861 – 1865) and is often compared to other famous inventors such as Thomas Edison, George Westinghouse, and Frank Sprague.

Granville T. Woods is a pioneering inventor with nearly 60 patents to his name. (Photo: Heritage Art/Heritage Images)

In 1887, Woods received a patent for the induction telegraph, a technology that enabled communication between moving trains and train stations. His invention was a much-needed improvement to the communication systems of the time, which were slow, unreliable, and could lead to train collisions.

Shortly after Woods received his patent, Edison sued him, claiming he had created similar telegraph technology first and should be granted the patent. Ultimately, Woods won the case, but at a significant financial and personal cost.

“Woods’ life – sometimes closer to a nightmare than the American dream – starkly illustrates the harsh reality of being a Black inventor in the late 19th century,” historian Rayvon Fouché wrote in the book Black Inventors in the Age of Segregation: Granville T. Woods, Lewis H. Latimer and Shelby J. Davison, published in 2003. Ironically, Woods was dubbed the “Black Edison” by the press for his contributions to science.

Granville T. Woods and His Inventions

Woods was born in Columbus, Ohio, in 1856. At the age of 10, he had to leave school because his parents could not afford tuition. Woods became an apprentice at a railroad shop, laying the groundwork for his engineering career.

Woods held nearly 60 patents in his name. His inventions revolutionized the transportation industry, including the Dead Man’s Handle – an automatic brake that slows a train when the driver is incapacitated. Woods was also granted a patent for an invention that led to the creation of the “third rail”, a crucial tool that provides electricity to trains for movement, according to the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) and the National Inventors Hall of Fame.

Some biographers have noted that Woods spoke and dressed elegantly, often wearing all-black attire. At times, he referred to himself as an immigrant from Australia, perhaps to garner more respect than identifying as African American.

Woods founded Woods Electric Company in Cincinnati, Ohio, and developed a gasoline-electric hybrid vehicle. (Photo: Wikipedia).

The Legal Battle with Edison

The multi-channel synchronous railway telegraph system, which allowed for continuous communication between trains, is one of Woods’ most significant inventions. However, before filing for a patent, Woods contracted smallpox and was bedridden for months. Upon recovering, Woods was shocked to discover that another inventor, Lucius Phelps, had been credited with creating a version of the induction telegraph system.

Woods meticulously used notes, sketches, and a working model of his invention to prove that he had started developing the technology first, successfully obtaining the patent in 1887.

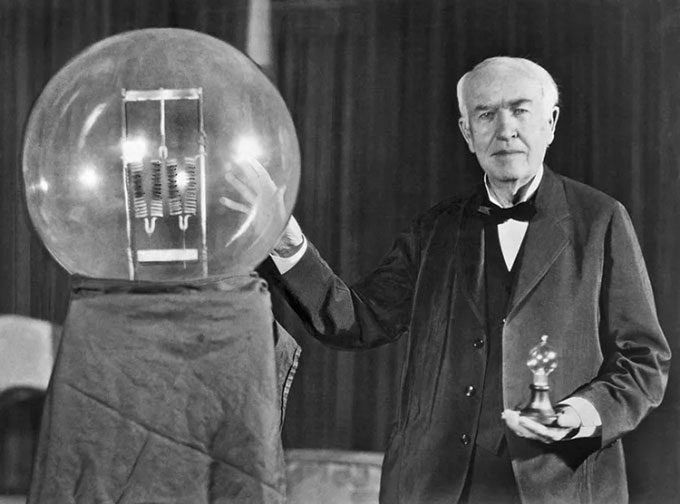

But the patent battle was not over. Edison sued Woods not once, but twice, claiming he had invented the induction telegraph first. Woods won both lawsuits. According to some historians, Edison offered Woods a job at the Edison Company, but Woods declined.

Thomas Edison holds a light bulb at a party in New Jersey, USA, in 1929. (Photo: Underwood Archives)

The Challenges of Being a Black Inventor

Ultimately, Woods had to sell some of his patents and equipment to Edison and other industrial capitalists, including companies like Westinghouse, General Electric, and American Engineering. Historians suggest that Woods’ decision to sell the patents he fought hard for illustrates the difficulty in promoting inventions by Black Americans to predominantly white buyers.

“Like most Black inventors of that era, Woods had to acknowledge that the race of the inventor affected the market value of that invention“, wrote Michael C. Christopher, a researcher at the University of Texas at Austin, in the Journal of Black Studies.

Some buyers of Woods’ inventions did not compensate him fairly or failed to recognize his contributions. Occasionally, inventors lost all rights to their inventions after selling them and received no profit at all.

Woods passed away from a brain hemorrhage in 1910, living in poverty and nearly forgotten for decades. It wasn’t until 2006 that he was inducted into the National Inventors Hall of Fame.