The quest to harness nuclear fusion has reached a new milestone as the JT-60SA, the largest and newest nuclear fusion reactor in the world, became operational last week.

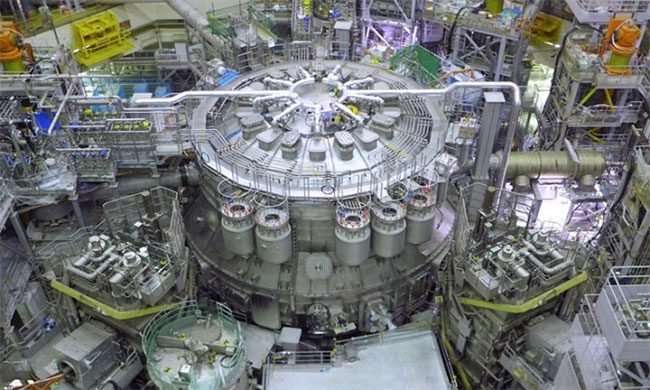

The JT-60SA reactor in Japan utilizes magnetic fields from superconducting coils to confine a superheated ionized gas cloud known as plasma within a vacuum chamber shaped like a doughnut, aiming to fuse hydrogen nuclei and release energy. This machine, standing as tall as a four-story building, is designed to maintain plasma at temperatures of up to 200 million degrees Celsius for approximately 100 seconds, longer than previous large tokamak reactors, as reported by Science on October 31.

JT-60SA is the largest nuclear fusion reactor in the world before ITER becomes operational. (Photo: National Institute for Quantum and Radiological Science and Technology, Japan)

This achievement demonstrates to the world that the “machine can perform its fundamental functions”, according to Sam Davis, project manager at Fusion for Energy, the European Union (EU) organization collaborating with the National Institute for Quantum and Radiological Science and Technology (QST) on JT-60SA and related programs. Hiroshi Shirai, the QST project director, indicated that it will take an additional two years before JT-60SA can produce plasma that lasts long enough for meaningful physics experiments.

The JT-60SA will pave the way for ITER, the massive international nuclear fusion reactor under construction in France, which aims to demonstrate that nuclear fusion can produce more energy than it consumes. ITER will rely on the technologies and operational methods that JT-60SA will validate. Japan is allowed to develop the JT-60SA and two other smaller nuclear fusion research facilities in exchange for agreeing to host the ITER reactor in France. The terms to upgrade the JT-60 reactor were included in a 2007 agreement between Japan and the European Union. This research reactor originated in the mid-1980s, and the building housing the JT-60 remains in place while the reactor is being rebuilt from scratch at an undisclosed cost.

Standing at 15.5 meters tall, the JT-60SA reactor is about half the height of the ITER reactor and can contain 135 cubic meters of plasma (equivalent to one-sixth of ITER). Its plasma will allow physicists to study plasma stability and how it affects electrical power. The insights gained can be applied to ITER, according to Alberto Loarte, head of the project’s science division.

Like many fusion projects, JT-60SA has faced multiple delays, extending its construction period to over 15 years. The original plan was for the reactor to be operational by 2016. Reasons for the delays include redesigns, supply issues, and the Tohoku earthquake in March 2011. Later, during testing in March 2021, a power cable supplying one of the superconducting magnets short-circuited. Due to inadequate insulation at a critical connection, the incident caused helium leaks, degrading the cooling system. To ensure safety, the JT-60SA project team had to redo the insulation on over 100 electrical joints, a task that took 2.5 years. The accident also prompted engineers working on the ITER project to plan more thorough inspections of the coils, according to Shirai.

One limitation is that JT-60SA will only use hydrogen and its deuterium isotope in experiments, not tritium, the third form of hydrogen that is expensive, scarce, and radioactive. Tritium is considered the most effective option for energy production, which is why ITER will begin using deuterium-tritium fuel in 2035.

The ITER reactor, currently under construction in Cadarache, southern France, will have a magnetic field strength of 5 Tesla, more than 100,000 times that of Earth’s magnetic field, generated by 100,000 kilometers of superconducting wire made from a niobium-tin alloy at a temperature of -269°C. The plasma in the ITER reactor must reach a temperature of 132 million degrees Celsius, ten times hotter than the core of the sun. Although ITER is a prototype for future large tokamak reactors and does not generate electricity, the project will demonstrate that nuclear fusion is a viable energy solution without carbon emissions.

So far, no nuclear fusion reactor has come close to producing more energy than it consumes. This remains a significant hurdle as reactors require enormous amounts of electricity. ITER could pave the way for sustainable energy. The project is estimated to cost around $20 billion, making it the largest scientific endeavor on the planet.

By 2050, Japan hopes to build DEMO, a prototype power plant that will provide a stepping stone from the research conducted at JT-60SA and ITER towards the commercialization of nuclear fusion electricity.