For those interested in physics, this question is not an easy one, but after much time, we now have an answer.

From the farthest stars in the sky to the screen in front of you, light is everywhere. However, the exact nature of light and how it propagates has puzzled scientists for a long time. From Isaac Newton to Albert Einstein, the question of whether light is a wave or a particle has been raised.

Physicist Riccardo Sapienza at Imperial College London states that this question has been around for a long time, especially among scientists in the 19th century.

Today, the clear answer is: light is both a particle and a wave. But how did scientists arrive at this perplexing conclusion?

An illustration of light with vibrant colors. The question “Is light a particle or a wave?” has puzzled scientists for centuries (Image: DrPixel/Getty Images).

The first thing to clarify is the scientific distinction between waves and particles. Physicist Sapienza explains, “You would describe an object as a particle if you can identify it as a point in space. A wave is something that you do not define as a point in space, but rather you need to specify the frequency of oscillation and the distance between the maximum and minimum of the wave.”

The year 1801 marked the first compelling evidence for the wave nature of light. At that time, scientist Thomas Young conducted his famous double-slit experiment. He placed a screen with two holes in front of a light source and observed the light after it passed through the slits. The light striking the wall showed a complex pattern of bright and dark stripes, known as interference fringes.

As the light waves passed through each slit, they created spherical wavelets that interfered with each other, either adding or canceling out to achieve a final intensity.

If light were a particle, you would have two beams of light on the other side of the screen. However, we observe interference and light everywhere behind the screen, not just at the positions of the slits. This is evidence that light is a wave.

80 years later, scientist Heinrich Hertz became the first to demonstrate the particle nature of light. He discovered that when ultraviolet light strikes a metal surface, it generates an electric charge, a phenomenon known as the photoelectric effect. However, his observation was not fully understood until many years later.

Atoms contain electrons at fixed energy levels. When light is directed at them, it provides energy to the electrons, causing them to escape from the atom. The stronger the light, the faster the electrons are released. Yet in subsequent experiments stemming from Hertz’s research, some results appeared to completely contradict this classical understanding of physics.

Ultimately, it was Einstein who solved this puzzle, for which he was awarded the Nobel Prize in 1921. Instead of absorbing light continuously from a wave, atoms receive energy in packets of light known as photons, explaining seemingly strange observations such as the existence of a threshold frequency.

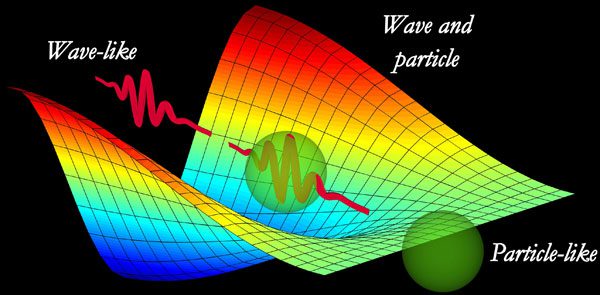

Light behaves as both a particle and a wave simultaneously. (Image: Livescience)

But what determines whether light behaves like a wave or a particle? According to physicist Sapienza, this question should not be posed. He states that light is not sometimes a particle and sometimes a wave, but “it is always both a particle and a wave.” “We just emphasize one of those properties depending on the experiment we are conducting.”

In daily life, we primarily perceive light as a wave, which is also the form that physicists find most useful in application.

According to scientists, by shaping a material with characteristics similar to light, we can enhance the interaction of light with the material and control the waves. For example, we can create solar energy absorbing materials that can absorb light more efficiently in energy production or develop magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) probes that are significantly more effective.