The successful 3D printing of the lightest material in the world – graphene aerogel – promises to open a new chapter in the materials industry.

Graphene aerogel is the lightest material in the world, weighing 7.5 times less than air, with one cubic meter of graphene aerogel weighing less than 160 grams. In fact, graphene aerogel is 12% lighter than the second lightest material, aerographite.

A common question arises: if it is lighter than air, why can’t this material float? This is because there are many gaps between the molecules of this material that allow air to seep in, preventing it from rising.

Graphene aerogel is the lightest material in the world.

With a humorous nickname of “frozen smoke,” aerogel is a type of solid that is flexible, conductive, compressive, and has excellent absorption capabilities.

Due to the unique properties of this material, scientists have discovered numerous potential applications ranging from cloaking devices to environmental cleanup. Just 1 gram of aerogel can absorb materials weighing up to 900 times its own weight, such as oil. This method is significantly cheaper than current market alternatives.

Currently, in many studies and experiments, silica aerogel is the most common form used for aerogel research. The challenge with this material lies in its difficult production process. However, scientists have tirelessly researched and successfully found a way to 3D print the lightest material in the world.

Recently, researchers from the State University of New York and the University of Kansas announced that they had successfully 3D printed aerogel material for the first time. The entire process is automated and uniformly controlled across all layers of the material.

A block of graphene aerogel can float on grass or even on top of flowers.

Aerogel itself is a layer of pure carbon atoms, thick and two-dimensional. They are arranged into a hexagonal honeycomb structure. To produce graphene aerogel, researchers must freeze the graphene layers and arrange them into a three-dimensional structure.

According to ScienceAlert, the successful use of 3D printing technology to create graphene aerogel for the first time highlights the commendable efforts of researchers, as the molecular structure of graphene aerogel is recognized as very challenging to print in 3D.

Researcher Akshat Rathi, part of the team that successfully 3D printed graphene aerogel, stated:

“Typically, to 3D print graphene aerogel, the main material is mixed with other components, such as polymers, to allow for printing on a machine. Once the structure is formed, the polymer is separated from the main material through another chemical process. However, in the case of aerogel, this method could destroy the crystal structure of the aerogel.”

The solution proposed by the research team is graphene oxide – a form of graphene combined with oxygen molecules. The team mixed this compound with water and placed it on a surface chilled to -25 degrees Celsius. At this temperature, the researchers were able to freeze each layer of graphene instantly, creating a three-dimensional graphene structure.

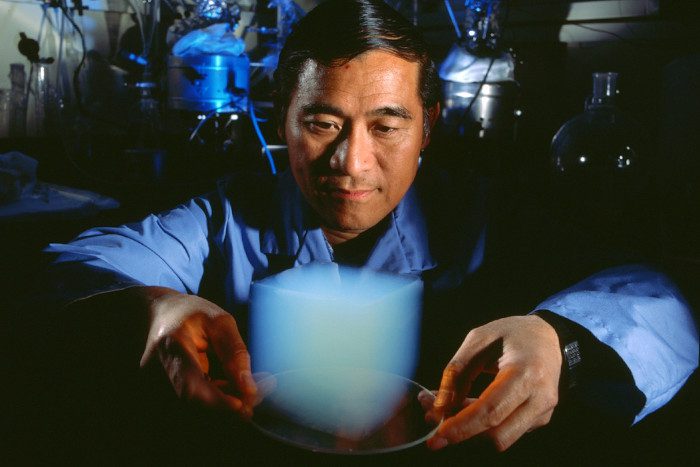

The 3D printing process of the lightest material in the world – graphene aerogel.

Rathi also added that after the 3D structure is completed, they will remove the ice blocks surrounding it by using liquid nitrogen to freeze-dry the water and separate it from the object’s surface without affecting the structure.

The aerogel material with the 3D structure will then be treated with heat to separate the oxygen atoms. The result will be pure graphene aerogel. According to Rathi, “the solid obtained will have varying densities from 0.5 kg/m3 to 10 kg/m3. The lightest graphene aerogel produced successfully weighs about 0.16 kg/m3.”

The advent of aerogel stems from a story told in the late 1920s when Samuel Kistler (1900-1975), an American chemistry professor, bet his colleague Charles Learned that “there exists a gel that is not liquid.” Naturally, no one believed he was correct, as the liquid characteristic had long been inherent to gels.

Through persistence and determination, after many experiments and facing numerous failures, Kistler finally discovered a gel in a gaseous state (not liquid), a new type of gel that had never been known, and no one had even imagined it. He became the first person to replace the liquid state of gel with gas and named it “Aerogel.” In 1931, he published his findings in an article titled “Coherent Expanded Aerogels and Jellies” in the scientific journal Nature.

Aerogels create excellent insulating materials as they almost nullify two of the three methods of heat transfer – conduction (they are almost entirely made up of insulating gases that are poor heat conductors) and convection (their microstructure prevents the movement of bulk gases). Aerogels can even have thermal conductivity lower than that of the gas they contain – a phenomenon known as the Knudsen effect.

Despite being extremely light, a material made of aerogel can “carry” another object that is 500 to 4,000 times its weight. When first introduced, aerogel found applications in every imaginable field, from women’s cosmetics to more romantic uses like paint for… napalm bombs. They are also used in cigarette filters and insulation components for refrigerators. Currently, aerogel can be found in fields such as swimwear production, firefighter clothing, glass doors, rockets, paint, cosmetics, and nuclear weapons…