Algebra is an important branch of mathematics, marking a significant advancement beyond arithmetic in the history of mathematics. In arithmetic, you work with specific numbers, while in algebra, your focus is on the relationships between numbers and abstract structures with generalized quantities. What benefits does learning algebra bring to our daily lives? We invite you to read Part 2 of this two-part series on the nature of algebra in schools and its significance.

Algebraic thinking, a method of thinking that allows for quicker and more accurate handling of complex problems.

Why do we use “X” as a variable in mathematics?

Part 2: The significance of algebra in life and some insights into algebraic thinking

Summary of Part 1: The difference between arithmetic and algebra, an overview of algebra in schools

This series is a summarized translation from Dr. Keith Devlin’s blog, a renowned mathematics professor at Stanford University, known for his over 100 published books and research papers.

Is mastering algebra (for instance, mastering algebraic thinking) worth the effort? Certainly, even though you will face challenges in striving to reach that goal, based on what you will find in most school algebra textbooks.

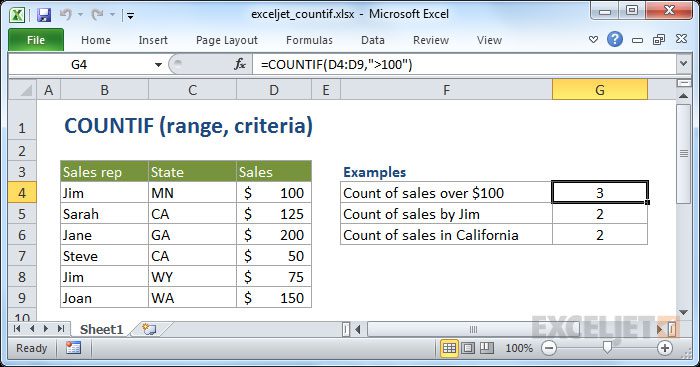

In today’s world, most of us truly need to learn how to master algebraic thinking. For example, you need algebraic thinking if you want to write a macro to calculate cells in a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet. This single example illustrates why algebra, rather than arithmetic, should be the primary focus of math education in schools. With spreadsheets, you don’t need to perform arithmetic problems; the computer will do it, much faster and more accurately than any human could. What you—the human—must do is initially create that spreadsheet. The computer cannot do that for you.

The issue is not what you use the spreadsheet for, whether it’s calculating scores for a sports tournament, tracking finances, managing a business/club, or finding the best way to equip your character in World of Warcraft. The problem is that you need algebraic thinking to set up the spreadsheet to accomplish what you want. This means thinking about numbers in a general form rather than as specific quantities.

According to Dr. Keith, while spreadsheets may provide today’s students with applications that are more satisfying and meaningful than problems about trains leaving stations or the number of hoses in a swimming pool that his generation had to “endure,” the necessity of algebra does not make the subject any easier. However, in a world where the livelihoods of nations depend on leading the technology curve, equipping students with the thinking skills that the world needs is crucial. The ability to use computers is one of those skills. And the ability to use computers for arithmetic problems requires us to have algebraic thinking.

The ability to use computers for arithmetic problems requires us to have algebraic thinking. (Image: Exceljet).

Reflections and Questions on the Philosophy of Algebra

Dr. Keith Devlin’s article has helped many understand why they struggled with algebra in their school years, and it has also received numerous shares and inquiries about algebraic thinking. Below are some insightful questions and comments from readers, along with Dr. Keith’s responses.

1. The comparison between algebra and Microsoft Excel is excellent. I often tell my students that algebra is like running through tires in soccer training. You would never run through tires in a soccer match, but you do it to train your legs to run well. Similarly, algebra is learning how to think logically and solve problems. No boss will ask you to factor a polynomial, but they will ask you to solve a problem logically. (Eric Blask)

(Image: Youtube)

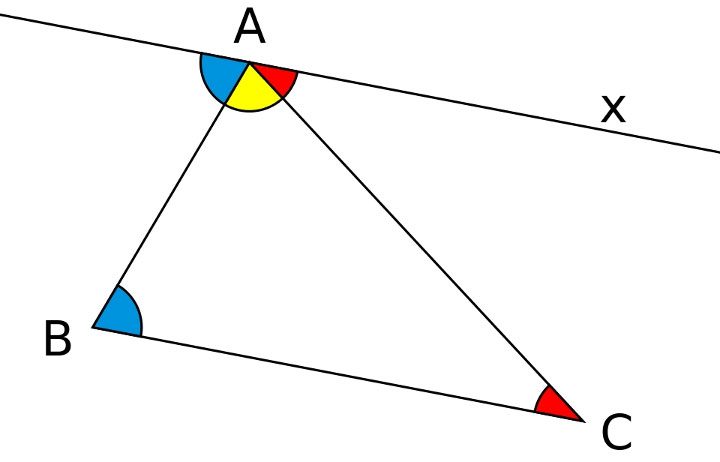

2. More than just problem-solving, algebra involves solving problems related to symbols, meaning working with abstract symbolic representations. This morning, as I thought about why so many students excel in geometry but have to “fight” with algebra, I realized it relates to abstract symbols. A standard geometry course does not involve many abstract symbols, except for courses that mix algebra. The symbols are quite simple and often relatively specific, such as letters representing angles (A, B, C…), or letters denoting side lengths (these types of labels are relatively classic symbols, much like arithmetic symbols or language), which you can place confidently into a diagram. Even geometric proofs are relatively specific in how you work with a diagram (which can be problematic!), and the abstraction here is different from that in algebra.

Excel tricks seem to make abstract algebraic symbols more concrete because you can change input cells and see output cells change. Thus, you become accustomed to visualizing the changing/temporary meaning of a symbol in various ways that, without Excel, you would have to imagine in your mind. Therefore, this could be a way to consider the difference—algebraic symbols can represent different things in different contexts, due to their nature. Algebraic symbols tend to behave according to time/change.

In practice, this is also true for geometric proofs, except for one thing: in our enthusiasm for student success, we have eliminated the issue of change—we try to draw a single representative diagram (among variables/events without pseudo-relationships or ambiguous, unclear connections) and reason with it. Occasionally, I try to help a student “see” a theorem by imagining parts of the diagram moving, specifying constraints, and then observing what must remain unchanged.

For example, when increasing the degree of an angle in a triangle, we see that the other angles (or just one angle) must decrease by the same number of degrees. Intuitively, this establishes the judgment that “the sum of the angles” is a constant. What is that constant? Increase one angle until it approaches 180, and the other two angles approach 0; oh, that’s 180 degrees. This holds true for polygons in general, and in the general case, increasing (n-2) angles towards 180 will force the last two angles to equal 0! (David Lewis).

(Image: Wikipedia).

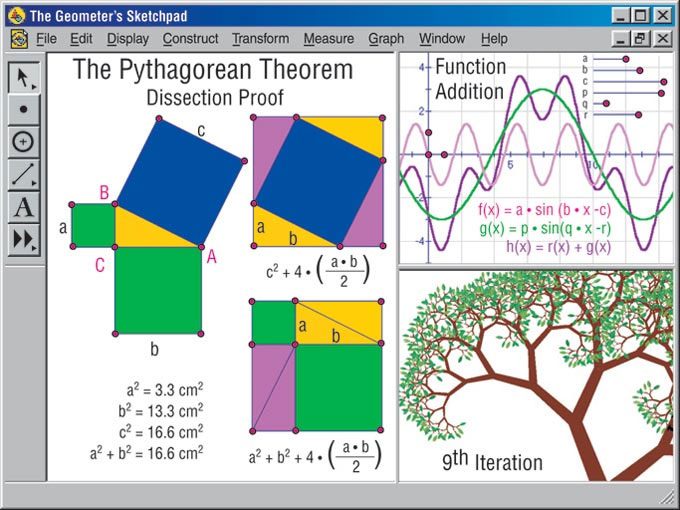

But I must say, this idea often doesn’t attract students as much as it does me. If I could do it in a “spreadsheet” for geometry, like Geometer’s Sketchpad (an interactive paid software for learning Euclidean geometry, algebra, calculus…), perhaps this idea would be better received. Thus, there is more evidence suggesting that the elements of time/change are new factors that make everything more elusive for students. And change is prevalent in algebra—just look at that world—variables! Therefore, algebra is even more than “thinking logically.”

Change is prevalent in algebra. (Image: KNILT).

Keith’s Reflection:

I agree that advanced algebra (also known as modern algebra) is inherently symbolic/abstract, but the algebra taught in schools, which is the focus of my article, is not like that. In fact, verbal algebra has been practiced for thousands of years until the symbolic method was introduced by Viete in the 16th century (as noted in Part 1).

In my book “The Math Gene” published in 2000, I explored the cognitive issues that people encounter when faced with abstraction. If the goal is to teach classical algebra (or algebraic thinking), then it may not be necessary to emphasize abstract symbols too much, and I believe spreadsheets are a good way to establish those symbols.

Of course, the ability to manipulate abstract symbolic structures is also valuable. But as the use of spreadsheets today is a useful skill for everyone, mastering abstract symbolic systems is less critical, as many find it difficult or are unable to grasp those systems. Therefore, we may need to postpone using many symbols until students have mastered algebraic thinking.

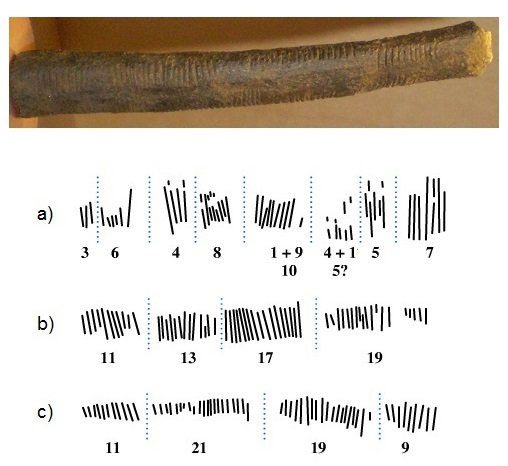

3. “Numbers originated first as currency, and arithmetic emerged as a means to use money in commerce” (a point raised in Part 1). Do you think so? What about the numbers represented by mammoth drawings on cave walls?

Keith: You’ve raised an interesting and nuanced point. What you describe is not related to numbers. It is a form of a primitive counting system. Counting systems were common in humanity’s early history, but they only required a one-to-one correspondence (which is the one-to-one correspondence between representative objects that resemble the items being counted and the actual items to be counted; since there were no digits, ancient people used representative objects for counting). It’s like “I have this one, I have many of those.” Numbers arise when you abstract them as intermediaries between a collection of objects and the related calculations. We see a similar stage of abstraction when young children learn. Initially, they grasp the idea of one-to-one correspondence, and only later do they understand the concept of numbers.

An ancient bone dating back 20,000 years engraved with tally marks. (Photo: CC-SA).

4. I wonder if someone can be very good at algebra but poor at arithmetic? (Jerry Lou)

Keith: Many professional mathematicians, including myself, have such tendencies. In fact, this may be due to (1) a lack of interest in arithmetic and (2) mathematicians hardly ever use arithmetic, so any progress they made in high school tends to fade due to lack of opportunities to use it. On the other hand, proficiency in arithmetic requires good memory, while in algebra, you can visualize everything logically, and that can continue more with mathematicians.