Anand Dhawaj Negi, a retired official who became a desert farmer, spent over 20 years transforming the frigid desert of Himachal Pradesh in northern India into a green oasis. In 1977, the Government of India initiated a program aimed at mitigating the negative impacts of desertification in the country’s hot and cold deserts.

AD Negi worked in the finance department responsible for the Desert Development Program and witnessed millions of dollars being wasted without any real results.

Whenever he asked the scientists and officials involved in the program why there was no progress, the answer was always that they lacked the technology to develop any sustainable crops in the harsh desert environment.

As the son of a farmer, Negi grew tired of the excuses and took leave in 1999 to address the issue himself.

By 2003, he quit his job to dedicate all his efforts to his developing desert oasis.

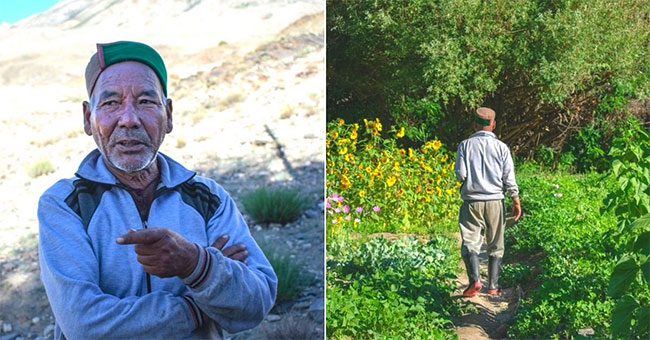

The man who spent two decades creating a green oasis in the frigid desert.

Originally from Sunam village in Kinnaur, Negi transformed a barren land in the frigid desert of Himachal Pradesh into a green oasis, just to show everyone, especially struggling farmers in the area, that it was possible.

This was not an easy task, but the former official knew what he had to do and possessed the ambition and patience to overcome it.

Negi’s initial efforts failed, as the seeds he sowed lacked sufficient water, marking the first challenge for this man.

He employed contour farming techniques—plowing sloped land along consistent elevations to conserve rainwater and reduce soil erosion—while working with the local community to create irrigation channels that diverted water from glaciers about 25 kilometers away.

After witnessing the results of his work, the regional irrigation department also began to collaborate.

However, water was just one of the challenges posed by the frigid desert. The sandy soil lacked the nutrients necessary to sustain the crops Negi wanted to grow, so he started a farm with around 300 Chigu goats and mixed their manure with earthworms to effectively double the nitrogen content in the soil.

This was further enhanced by the hectares of grass he planted around the oasis, which regularly decomposed as new plants replaced them. Thus, he overcame the initial problem he faced.

Rodents would come to eat the tasty plants, so the farmer planted grass around the more valuable crops. Since wild rabbits loved grass, they paid no attention to the other plants.

When he first began his work in Himachal Pradesh, AD Negi invested all his money in experimenting with various combinations of local farming techniques and more scientific farming methods. It was a labor-intensive process, but over time, the plant mortality rate dropped from about 85% to just 1%.

After proving that valuable crops like peas, potatoes, green beans, apples, and apricots could be grown even in the harsh desert environment, this former official began focusing on trees, as he saw them as essential to combat climate change in the region.

This was a labor-intensive process, but over time, the plant mortality rate dropped from about 85% to just 1%.

With the help of just two volunteers, Anand Dhawaj Negi transformed over 90 hectares of frigid desert into a green oasis, earning praise from both the local people and scientists.

People traveled from afar to witness this real-life miracle, some coming to purchase Negi’s organic fertilizers for their own farming, while others brought their livestock to graze, as it was considered the best feed in the region.

Sadly, Anand Dhawaj Negi—the healer of the desert—passed away at the age of 74 after a stroke. He is remembered as a local hero, and his green oasis is hoped to be preserved as a reminder that nothing is impossible.

Negi’s family plans to continue his work but has requested the government to take responsibility for the oasis and assist in its preservation.

Virender Sappa Negi told The Better India: “Before saying goodbye to us, he planned to plant some evergreen or coniferous trees like pines.”

“Now, as a family, we want to fulfill his last wish.”

“Additionally, we want the state authorities to take responsibility for his forest so that his work can inspire future generations.”