And then it sprawled out, sulking there as if to blame God: Why did evolution create a failure like me?

The leaps of frogs are often regarded as a marvel of evolution. When you see a frog crouching, compressing its hips backward, and then springing forward on its legs—two biological springs that are among the most powerful in the animal kingdom—the frog is executing a classic jump that has made its species famous.

And then it flies through the air, stretching its legs out like graceful long jumpers. The frog’s front legs fold back before extending forward, landing and supporting its whole cumbersome body that is hurtling like a cannonball.

“Thud,” the frog lands as if it has glued itself to the ground after tracing a perfect parabola through the air. All of this happens in the blink of an eye.

Most frog species can jump distances 10-20 times their body length, averaging about 1.5 meters. Notably, the South African sharp-nosed frog can leap as far as 3.3 meters, which is 44 times its size.

With that ratio, a long jumper standing at 1.7 meters would need to jump 74.8 meters to break the frog’s record. That’s equivalent to the combined length of two Airbus A320 aircraft.

Now, if you want to beat a frog in a long jump contest, you will have to choose a competitor that is more your size.

The good news is, there is a clumsy frog species that fits that description. A frog that would score zero points in any of its jumps. Because it always jumps like this:

The frog has a decidedly clumsy jump

The performance you just watched is part of a research project published in the journal Science Advances. In it, scientists are trying to decode why there exists a frog that performs such clumsy jumps?

Richard Essner, a biologist at Southern Illinois University Edwardsville, states that all other frog species have a perfect jump, with “very precise, controlled landings.”

However, for this species, Brachycephalus (also known as the pumpkin toadlet), they can only manage about half of the task. The frog still leaps into the air with all the hopes of its species riding on it, but the way it lands is simply unacceptable.

Its hind legs become stiff, the frog spins in the air like a ballet dancer but then falls flat on its face. Instead of landing softly on its front legs, the frog sometimes crashes its chest, back, or even its head into the ground.

And then it sprawls out, sulking there as if to blame God: Why did evolution create a failure like me?

Welcome to the story of the pumpkin toadlet: A frog with clumsy jumps

First, it should be noted that you can call them toads or frogs—it’s all acceptable. All toads are frogs, and they belong to the order Anura, meaning “tailless adults.” They represent the largest amphibian group on the planet with over 7,500 species.

However, toads have faced discrimination due to their warty and rough appearance. Toads primarily live on land, so their legs lack webs, and their hind limbs are quite short.

In contrast, not all frogs can be called toads. Because frogs have their own pride. Frogs have smooth skin, spend more time living in the water, have webbed feet, and longer thighs. Hence, frogs generally jump higher and further than toads.

So perhaps we should refer to them as pumpkin toadlets for clarity (in fact, if you search for “pumpkin frog” on Google, the results are mostly recipes).

As mentioned, the pumpkin toadlet’s scientific name is Brachycephalus. They are usually found in the southeastern forests of Brazil. Pumpkin toadlets are among the smallest frogs in the world, with a body length of only about 9.5 – 13.5 mm. This means one of these toads could comfortably sit on your thumbnail.

Its closest relative, the flea frog (Psyllophryne), is also rarely longer than 10 mm. Additionally, there are several other small frog species living in northeastern Brazil and Cuba, such as B. darkside, B. margaritatus, B. pulex, Eleutherodactylus iberia, and E. limbatus. All of these have body sizes measured in millimeters.

Scientists say that the small body size is an evolutionary advantage for Brachycephalus toads. These pumpkin toads need less food due to their small bodies. Moreover, because of their small body surface area, they can also hide better in the forest floor, burrowing under dry leaves without being detected by larger predators.

However, when a frog shrinks its body size, problems start to emerge. This is what causes the pumpkin toad to perform such clumsy jumps.

In their recent study, Richard Essner and colleagues examined the legs of pumpkin toads to see if there was anything wrong with their stick-thin limbs.

Essner found that pumpkin toads only have three functional toes, fewer than other frog species, but all of their leg muscles still function well. The frog’s jumping technique is also not problematic. They still jump quite high and far in the first half of the jump. The unusual events only occur in the second half of the jump when the frog lands.

It seems they cannot determine their elevation, misjudge the timing of their body in the air, and even lose their sense of direction towards the ground.

To find out why, Essner and Marcio Pie, a biologist at Edge Hill University in the UK, conducted an experiment. They subjected pumpkin toads to CT scans to see if there were issues with the vestibular system of these creatures.

Because when comparing their jumps to the staggering gaits and falls of vestibular patients, there seems to be a significant similarity.

We know the vestibular system is like a gimbal in the brain, functioning to stabilize the image of the world we see while keeping our bodies balanced.

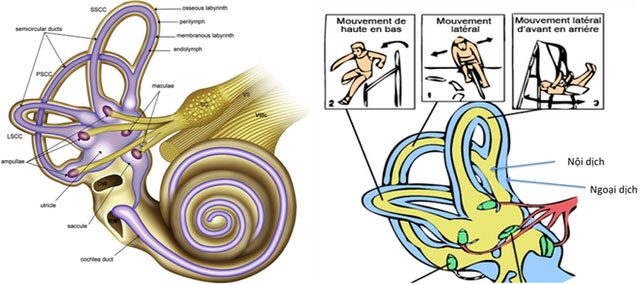

The vestibular system is located deep within the ear canal, with three semicircular canals filled with fluid. These semicircular canals are positioned at 90-degree angles to each other, lined with tiny hair-like structures. When we walk, the body’s movements cause the thick fluid to move within the semicircular canals of the vestibular system.

The fluid movement causes the tiny hairs to sway with each motion, sending signals to the brain, where our nervous system processes the vibrations and stabilizes them to help our vision and body maintain balance.

That is when the vestibular system encounters problems, or when you step off a merry-go-round, the vestibular system and disrupted fluid can cause dizziness, unsteadiness, and nausea.

Structure of the vestibular system.

The issues with pumpkin toads also occur there, within their tiny semicircular canals

It turns out that when a frog shrinks its body size, its brain and vestibular system in its inner ear also shrink to a critical threshold. Previous studies have found that small frog species may become deaf, unable to hear the calls of mates during mating season.

The issues with pumpkin toads are even more severe. Essner and Pie stated that when they examined the vestibular system within the ears of these frogs, they were so small they were almost useless. All three fluid-filled semicircular canals were astonishingly narrow. “We even had to measure them in micrometers,” Pie said.

In fact, pumpkin toads possess one of the smallest vestibular structures ever recorded in vertebrates while still being fully developed. And what is the consequence of this record?

Every time a pumpkin toad jumps into the air, the fluid in its vestibular system does not move but sticks to the sides of the semicircular canals due to friction. “It’s like trying to suck a thick syrup while pinching the straw; the fluid doesn’t have the same acceleration as their movements,” explains Marguerite Matherne, a mechanical engineer at Northeastern University.

This disruption ultimately prevents the pumpkin toad from determining its position in space. Despite jumping into the air, it does not know when it is about to fall to prepare for a safe landing.

Essner and Pie refer to this clumsiness with a euphemism: “uncontrolled landing.” All pumpkin toads, in all of their jumps, make the same mistake. “They jump like drunkards throughout their lives,” Pie said.

Now, if evolution has shrunk these frogs to the point of losing their vestibular function, the next question is whether these frogs can survive in a complex world.

In fact, the jumping instinct of frogs is a trait they have developed to escape from predators. When a frog senses danger lurking, it will jump away. And you rarely catch them, right?

Pie points out that, despite the clumsy jumps of the pumpkin toads, you still rarely manage to catch them. “Sometimes, the two of us can search all day and only end up catching one,” he says.

This is because pumpkin toads have employed a different evasion strategy. When they sense danger, they will still jump. However, that awkward landing actually helps the frog dive into the dense foliage on the forest floor. Now, the frog just needs to lie still there, motionless. It will be rare for any predator to find them again.

In Brazil, the pumpkin toad species is thriving. The tropical forest provides them with plenty of food, including numerous insect species that these tiny frogs can hunt and consume. During their hunting expeditions, pumpkin toads move very stealthily and slowly, much like chameleons.

At this pace, their vestibular system can still maintain the balance of their bodies. “And they are doing just fine,” Essner says. The only thing is, he wonders whether evolution will continue to shrink pumpkin toads and further reduce the function of their vestibular system.

“If the toads keep getting smaller, they may lose their vestibular function altogether,” Pie says. At that point, it’s uncertain how they will move and jump around.