Surrounding the Discovery of the “Largest Burial Cave in Vietnam” or “Ma Cave“, which contains hundreds of ancient wooden coffins “hung” and “buried” in mountain caves near the Ma River and Luong River, in Hoi Xuan commune, Quan Hoa district, Thanh Hoa, several questions have been raised: What is the relationship between the burial customs in Quan Hoa and those of residents in some neighboring countries?

Burial Customs Around the World

The custom of burying the dead and placing coffins in caves is a fairly common phenomenon globally, primarily in mountainous regions of Asia (especially in Turkey and China) and the Americas (where the Indigenous peoples, descendants from Asia, have lived for over 10,000 years).

The origins of this custom relate to the symbolic nature of caves – the first home of humanity. Thus, caves are equated with the womb of a woman, the place where humans are born, and to be reborn or resurrected, the dead need to return there. Mountains are also seen as a connection between earth and sky, the closest place to the heavens, thus making them the best locations to bury the dead (ancient Chinese emperors were often buried in caves so their souls could easily ascend to heaven and become ancestors – deities).

Caves used for burial can be natural or man-made (Egyptian pharaohs were buried in pyramid-shaped tombs). A variant of the burial custom involves interring the dead in stone coffins, within stone-capped graves (still observed among the Hmong) and burial sites with stone pillars (present in areas inhabited by the Muong people)…

“Ma Cave” in China

In China, the term “ma cave” is no longer a shocking phenomenon, as it has been discovered in 13 provinces and autonomous regions, from Sichuan province in the west to Fujian province in the east, from Shaanxi province in the north to Guangdong province in the south. In the city of Shangluo, Shaanxi province, archaeologists have uncovered 680 sites with 4,220 burial caves (natural or man-made) containing wooden coffins placed inside the caves or hung on steep rocky slopes. Most of the single burial caves are rectangular and 3 meters deep. In collective burial caves, images of kitchens, wells, and shrines are carved into the walls.

The most famous burial site in China is located on Longhu Mountain in Jiangxi province, considered a “Heavenly Palace” due to its breathtaking scenery, and it is also the birthplace of Taoism. Here, on the rock walls along the river, at heights ranging from 20 to 300 meters and facing east, there are hundreds of caves or burial pits, each containing one or more wooden coffins shaped like houses or boats, weighing between 150 to 500 kg.

The artifacts found within these coffins indicate that their owners were the Baiyue people who lived during the Spring and Autumn – Warring States period (770 to 221 BC). Due to the large number of burial caves distributed over a rugged and unique terrain, this mountain is honored as the “Number 1 Natural Archaeological Museum” of China. In 1983, it was placed under special preservation by the Chinese government and in 2000, it was designated as one of China’s 11 national geological reserves.

Over 10,000 people, including scholars and local residents, have offered various interpretations. Some believe that more than 2,000 years ago, the river levels were higher than today, so ancient people may have used boats to transport coffins to caves not far from the riverbank. Others suggest that the burial caves were originally in lowland areas, but due to geographical changes, they have been elevated to their current heights.

Another theory proposes: ancient people created burial caves high on cliffs to protect their ancestors’ tombs from desecration, and to achieve this, they built a scaffolding system using bamboo and wood or employed pulleys to hoist heavy coffins from boats. Some even hypothesize that ancient people used balloon-like devices or primitive cranes to move the coffins up the cliffs. Some research groups have conducted experiments to recreate traditional methods of lifting people and heavy objects to high places. However, no explanation has been universally accepted.

“Ma Cave” in Indonesia

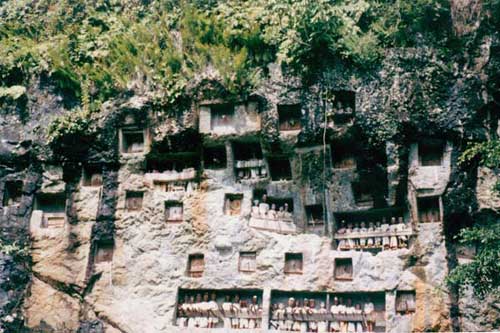

In Indonesia, the burial custom has been persistently preserved among some Toraja groups on Sulawesi Island. Interestingly, some scholars believe that their ancient ancestors migrated from Đông Sơn, Vietnam, or from Indochina. Due to a relatively stable and isolated geographical-historical context, the traditional Toraja culture has retained many Đông Sơn customs until recently, such as tattooing, filing teeth, chewing betel, playing gongs, or using mortars as signals during funerals.

Toraja funeral statues overlooking the fields,

villages of the living. (Photo: tabisite.com)

Notably, the traditional Toraja house (tongkonan) bears a striking resemblance to the curved-roof houses depicted on the Đông Sơn bronze drums from the Hoang Ha period. Researchers have also noted that Toraja pestles for pounding tree bark are identical to those from the Phung Nguyen culture, as well as a near-perfect similarity in patterns between a Toraja bamboo tube and a Central Highlands bamboo tube.

Even today, in some areas, the Toraja still preserve the burial custom, which involves placing coffins (often belonging to dignitaries or wealthy individuals) in man-made caves on cliff faces. These coffins are typically shaped like buffalo (a mythical creature regarded as the lord of the underworld) or boats (similar to the homes of the living). Interestingly, they refer to these burial caves as liang (cave) or lo’ko (hole), terms that are clearly very similar to the Vietnamese words for cave and hole.

Human skull in “Ma Cave” Indonesia (Photo: tabisite.com)

For the Toraja, the burial custom is associated with the belief that the resting place of the dead is in the west or south, “the place closest to the sky,” “the place with a heavenly door,” “the place with a ladder connecting earth and heaven,” “the upstream of a river,” linked to the legend of their ancestors who “sailed to a new land.” Consequently, the ideal burial location is in mountain caves. The act of taking the dead to these sites is believed to help their souls attain peace and ascend, so they can bless the living and be easily reborn in a new life.

Today, Toraja funerals and burial caves have become two “tourist products” of Indonesia.

The Connection Between Burial Practices in Quan Hoa and the Plain of Jars in Laos

|

| One of the stone jars at the Plain of Jars. (Photo: CAND) |

In Laos, the Plain of Jars, with over 3,000 large stone jars (height: 2 – 3 m, 25 m; mouth diameter: 1-3 m; weight: 2-13 tons), is the most famous archaeological site and also one of the most mysterious. In the future, it is likely to be recognized as a World Heritage Site.

Many intriguing legends and scientific hypotheses surround three main issues: the creators, dating, and the function of these stone jars.

According to the scientific hypothesis most supported by scholars to date, the Plain of Jars is essentially a large cemetery where the jars serve as coffins or containers for the bones of the cremated dead in a nearby cave. Most of the burial artifacts found in the cave and in the jars date from the 5th century BC to the 8th century AD. Some pottery artifacts have shapes closely resembling those of Đông Sơn bronze drums, indicating a cultural connection between the Plain of Jars and Đông Sơn culture.

Meanwhile, in Thailand, archaeologists discovered an important burial site in Ongbah Cave with over 90 wooden coffins shaped like boats dating from 403 BC to 25 AD. Fortunately, among the artifacts that survived local looting, six bronze drums remain. Notably, the skeletons in the coffins indicate that their owners were taller than the indigenous Southeast Asian population. This has led some scholars to associate the owners of the coffins in Ongbah Cave with those of the Plain of Jars, and subsequently, with the ancient legends and scientific hypotheses regarding the migration of Indo-European peoples from Central Asia through India to Southwest China and into Indochina.

Currently, perhaps the greatest mystery of the Quan Hoa burial sites lies in the unusually large skeletal remains found. It is hoped that future DNA analyses will uncover these mysteries and reveal connections between the owners of the burial sites in Quan Hoa, the Plain of Jars, and regions beyond.