When discussing ancient Egyptian mummies, people usually think of pharaohs, while the mummies of ordinary citizens are often overlooked. The recent excavation of hundreds of mummies by three French scientists in the Nile region has revealed much information about the lives of ancient Egyptians.

When discussing ancient Egyptian mummies, people usually think of pharaohs, while the mummies of ordinary citizens are often overlooked. The recent excavation of hundreds of mummies by three French scientists in the Nile region has revealed much information about the lives of ancient Egyptians.

Excavating the tombs of King Ramses or Tutankhamun, which are still intact, does not fully depict the daily lives of their subjects. In this context, the excavation results of nearly 800 mummies in the Nile basin by the three French scientists provide a unique evidence of the social circumstances and living conditions of an ancient agrarian community living on the fringes of the glorious Egyptian dynasties, marking a significant success in uncovering the lives of ancient people.

The study of these 800 mummies, which include men, women, and children from the Kharga Oasis (west of Aswan), by a team of three scientists from different fields (archaeology, medicine, and anthropology) has vividly reconstructed the picture of the lives of ordinary ancient Egyptians. These mummies belonged to farmers who settled and cultivated in Kharga, a rather arid land. They transformed it into an oasis “full of water and wine,” as noted by the Roman historian Strabo. The remnants of powerful fortifications indicate that an army was stationed there in the 3rd century AD to protect this fertile land from foreign incursions.

The lives of these forgotten communities living on the margins of ancient Egyptian dynasties have been vividly depicted by François Dumand, Roger Lichtenberg, and Jean-Louis Heim. Unlike previous studies on Egyptian mummies, these three French scientists conducted their research directly at the excavation site. Their findings reveal that these mummies belonged to ordinary people who lived during the Ptolemaic period and later under Roman rule from the 1st century BC to the 4th century AD. Today, the residents of Ain Labankha, Douch, and El Deir (three locations of the mummies’ excavation in Kharga Oasis) can better understand the origins of their lifestyle, dietary habits, and mourning customs.

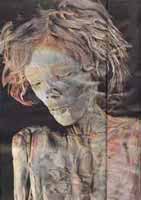

While excavating a tomb located on a hillside in El Deir, the scientists discovered that the mummies in this tomb belonged to a family, remarkably preserved, displaying emotional expressions of the living. They even noted the expression of suffering evident on the face of a young girl, about 10 years old, within this family. Her ten fingers were curled up as if she were enduring excruciating pain. The mummies of a man, several women, and an elderly person still retained their hair, eyelashes, and nails.

After conducting analyses using various research methods such as X-raying the mummies and performing autopsies, researchers found that these mummies suffered from unusual diseases of that time, such as tuberculosis, which claimed nearly half the family members, a case of typhoid, appendicitis in the son, and two cases of pituitary cancer.

In the small town of Douch, researchers found that the lives of the inhabitants there were far more difficult compared to the other two areas. The study results showed that the mummies here had previously suffered from severe malnutrition, paralysis, or acute rheumatism. 60% of the mummies were malnourished, with some even being pregnant. This rate was significantly higher than those excavated at Ain Lakha and El Deir, where only 4% were found among pharaohs.

To explain this disparity, scientists believe that the residents of Ain Labakha and El Deir had additional sources of income beyond agriculture. This allowed them to significantly improve their quality of life. The incidence of acute rheumatism in these two areas was lower than in Douch, and the mummification processes were of higher quality. Many individuals from all three excavation sites bore scars from schistosomiasis, a disease prevalent in ancient Egypt.

A recent discovery of a mummification site in El Deir confirms that the mummification practices in these oases date back a long time. A large quantity of pottery of various types, used for different purposes, and essential items for mummification were also unearthed. These included jars for holding perfumes and containers of a black resin used to coat the mummies. Researchers also found a type of natural stone placed inside the mummies to keep them dry.

In January, these three French scientists discovered a cemetery near El Deir. Here they found 150 mummies of sacred animals of ancient Egyptians, primarily dogs. According to the scientists, these dogs symbolize the local people’s worship of the god Oupouaout, a representation of a desert dog. They further noted that there are still many mysteries about ancient Egypt that humanity has yet to uncover. However, these recent discoveries clearly mark a significant advancement in archaeology related to the study of ancient Egyptian civilizations.