For many years, there have been whispers and rumors. These tales, often shared in hushed tones, are not secrets, yet they remain largely unspoken in public. Meanwhile, those who know the truth have longed to share their stories with the world.

They wish to reveal the truth about the minds kept in the basement. As a child, Lise Søgaard was aware of the whispers, albeit in a slightly different context, as it was a family secret too painful for her relatives to voice.

Søgaard didn’t know much, except for a family member who seemed to exist solely in a photograph hanging on the wall of her grandparents’ home in Denmark.

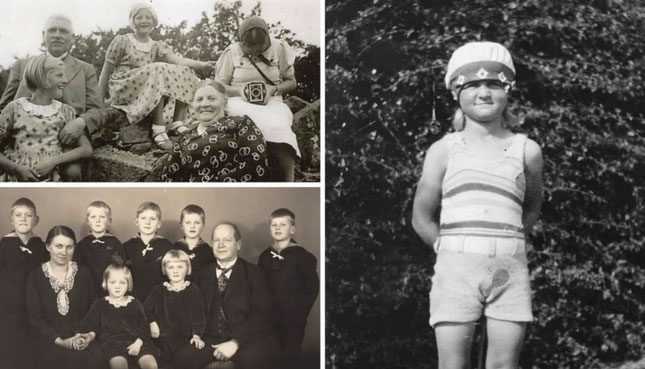

Kirsten (middle of the top photo) and her sister Inger (right side of the bottom photo) posing with family in the 1930s

The girl in the photograph is Kirsten, the younger sister of Inger, Søgaard’s grandmother.

“I remember looking at the photo and thinking, ‘Who is that girl? What happened to her?’” Søgaard recalls.

As she grew older, Søgaard’s curiosity remained. In 2020, she visited her grandmother, who was over 90 years old and residing in a nursing home in Haderslev, Denmark. After much hesitation, she finally mustered the courage to ask her grandmother about Kirsten. It seemed that Inger had been waiting for this moment, as she began to share a long story that was beyond Søgaard’s imagination.

Kirsten Abildtrup was born on May 24, 1927, the youngest of five siblings. Inger remembers Kirsten as a quiet and intelligent child. The two sisters were extremely close. However, when Kirsten turned 14, something began to change.

Kirsten experienced emotional outbursts and cried for long periods. Inger asked their mother if it was her fault, given how close they had been.

“On Christmas, the whole family was supposed to visit relatives. But our great-grandmother and my father stayed home with Kirsten and sent all the other children away,” Søgaard recounts.

When the children returned, Kirsten was no longer at home. This marked her first hospitalization, the beginning of a long and painful journey that ended with Kirsten’s death. She was diagnosed with schizophrenia. Kirsten was admitted to the hospital during the closing stages of World War II, as Denmark and other European countries were on the brink of peace.

Like many other places, Denmark was struggling with mental illness at that time. Psychiatric facilities were built across the country to accommodate patients. However, the understanding of what was happening in the brain was still limited. The same year peace returned to Denmark, two doctors came up with an idea.

When patients died in psychiatric hospitals, they were often autopsied. The two doctors thought that their brains should be removed for preservation.

Thomas Erslev, a historian of medical science and research advisor at Aarhus University, estimates that about half of the psychiatric patients in Denmark who died between 1945 and 1972 donated their brains. Their brains were stored at the Brain Pathology Institute, affiliated with the Risskov Psychiatric Hospital in Aarhus, Denmark.

The two doctors, Erik Stromgren and Larus Einarson, were the architects of the hospital. After about five years, pathologist Knud Aage Lorentzen took over the institute and spent the next three decades building the collection.

The final count was 9,479 human brains, believed to be the largest collection of human brains anywhere in the world.

Dr. Martin Wirenfeldt Nielsen is now the curator of the human brain collection. (Photo: CNN)

The Numbered Buckets

In 2018, Dr. Martin Wirenfeldt Nielsen received a call. The human brain collection had to be relocated. Financial constraints meant that it could no longer remain in Aarhus, but the University of Southern Denmark in Odense wanted to take it in.

Each greenish-yellow plastic bucket contained a formaldehyde-preserved brain, placed into a white bag and numbered for easy transport to a spacious basement on the university campus.

Among them were nearly 5,000 brains from patients with psychosis, 1,400 from those with schizophrenia, 400 with bipolar disorder, 300 with depression, and others with various conditions. What sets this collection apart from any similar collection in the world is that they were gathered before modern medications were available to treat brain disorders.

However, this collection has also sparked controversy. In the 1990s, public awareness in Denmark began to grow, leading to intense debates about scientific ethics.

Dr. Knud Kristensen noted that at that time, there was a viewpoint suggesting that the collection should be destroyed, either by burial or by relinquishing it in an ethical manner. “Another opinion was that since harm had already been done, the right course of action now was to ensure that these brains were used for research,” Dr. Knud Kristensen shared.

After years of debate, the Danish National Association for Mental Illness changed its stance and strongly supported retaining the collection. By 2018, the ethical debate had quieted down. Wirenfeldt Nielsen became the curator of the collection.

Years later, he received a message from Søgaard. She inquired whether he had the brain of a woman named Kirsten.

After many attempts to search and piece together clues, Søgaard eventually found her aunt’s brain in bucket number 738. Since then, Søgaard has been working to break the stigma surrounding mental illness by sharing personal and family stories with the world.

“My grandmother was very moved. She also said that she feels closer to her sister now,” Søgaard recounted.