The history of humanity has largely forgotten the “precious gem” of Khotan, the cradle and cultural bridge of Buddhism located on a branch of the Silk Road.

“Everything Changes”

One of the most fundamental teachings of Buddhism is “everything changes” – and this applies even to the religion itself. In places where the Dharma once flourished, it may have vanished, and in places far from the origins of Buddhism, it may have taken root. Time and place, history and geography are always in flux.

This is certainly the case for the ancient Buddhist kingdom of Khotan, a land believed to have formed from the drainage of a mountain lake.

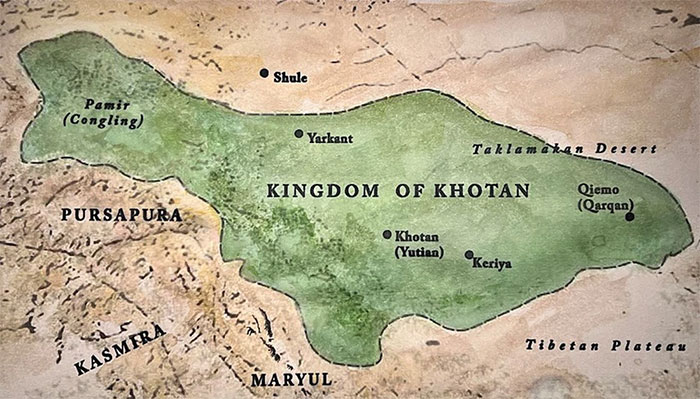

Map of the ancient kingdom of Khotan. (Photo: Tricycle).

Khotan is the name of an oasis and a large city located on the ancient Silk Road, a trade network that connected Europe, India, and China through vast deserts in Central Asia for over 2,000 years.

To the north of Khotan lies one of the driest and most desolate desert climates on Earth, the Taklamakan Desert, and to the south is the largely uninhabited Kunlun Mountains (Qurum).

To the east, there are very few oases outside of Niya, making travel difficult and access relatively easy only from the west. The territory of the kingdom today lies within Xinjiang, China.

The vast desert covering the Tarim Basin in Central Asia. (Photo: Thoughtco).

According to historical records, Khotan was once a dual colony, first settled in the 3rd century BCE by an Indian prince, one of the sons of the legendary Emperor Ashoka [304-232 BCE], who was exiled from India after Ashoka converted to Buddhism.

The second settlement was established by an exiled Chinese king. After a battle, the two colonies merged.

In the centuries preceding the Common Era and in the first millennium CE, Khotan was a small but extremely important kingdom.

Despite enduring many waves of migration, invasion, and domination by powerful states from the west and east, Khotan always managed to survive thanks to its abundant resources of jade and silk production.

Portrait of Li Cheng Tian, the 10th-century king of Khotan. (Photo: Wiki).

But above all, geography remained the most crucial factor for the kingdom – an oasis situated on the largest trade route in the region at that time. A small and not very powerful kingdom became a stronghold of Indian culture during or shortly after the reign of Emperor Ashoka.

The kingdom flourished, perhaps during the pre-Mahayana Buddhist period in the 1st century BCE; it was connected to the ancient kingdoms of Gandhara and Kashmir to the northwest of India.

Khotan also played a significant role in spreading Buddhism from India to China. In the 3rd and 5th centuries BCE, the texts “Prajnaparamita” and “Avatamsaka Sutra” were first translated into Chinese from ancient manuscripts found in Khotan.

The daughter of the King of Khotan married the ruler of Dunhuang, Gao Yanlu, wearing an intricately jade-studded crown. (Photo: Wiki).

The Birth of the Kingdom

Mythical stories about the birth of the kingdom revolve around the draining of a lake by the command of the Buddha Shakyamuni. This place is considered a land marked by the Buddhas of the past and blessed.

One of the two scriptures that preserve the story of the legendary birth of the land is the “Prophecy on Mount Goshringa.” This scripture recounts the image of the Buddha flying to the land of Khotan with a large entourage, blessing the living beings in the lake.

The head of the Buddha found in Khotan around the 3rd-4th centuries. (Photo: Wiki).

He also granted sacred mountains, stupas, and many sites; teaching there and prophesying the future importance of Khotan as a land that would sustain and preserve the Dharma.

At the end of the scripture, the Buddha instructed his disciple Shariputra and the Holy King Vaishravana to deploy supernatural powers and drain the large lake into a river.

They cut a mountain into two large pieces and moved them out of the way so that the lake could drain into the nearby Gyisho River. However, no one is certain where the mythical lake might have once been.

The famous Silk Road. (Photo: Thoughtco).

In another scripture – “The Questions of Vimalaprabha”, the story of Khotan’s birth is entirely different. When the Buddha foresaw the rise of Khotan as a religious kingdom in the century after his parinirvana, he commanded the gods and bodhisattvas to protect the inhabitants of the land.

At the end of the scripture, the Buddha vanished from the summit of Mount Gridhrakuta and returned to meditate in Khotan, along with the bodhisattvas seated on lotus thrones floating in the large lake, where the stupas and monasteries of the future land would appear as the lake drained.

The Golden Age

The main export item of the kingdom of Khotan was jade, and Khotan green jade began to be imported at least 1,200 years BCE.

By the time of the Han dynasty (206 BCE – 220 CE), the main export goods from China through Khotan were silk, lacquerware, and gold ingots, exchanged for jade from Central Asia; silk and other textiles including wool and linen from the Roman Empire; glass, wine, perfume, and slaves from Rome.

There were even rare animals such as lions, ostriches, and zebras, including the famous horses from the Ferghana Valley.

A Khotan jade seal from the Qing dynasty, during the reign of Qianlong. (Photo: Greelane).

During the Tang dynasty (618-907), the main traded items moving through the kingdom of Khotan included textiles, such as silk, cotton, and linen; metals, incense, and other fragrant substances, furs, animals, ceramics, and precious minerals.

Minerals commonly included lapis lazuli from Badakhshan, Afghanistan; agate from India; coral from the Indian coast; and pearls from Sri Lanka.

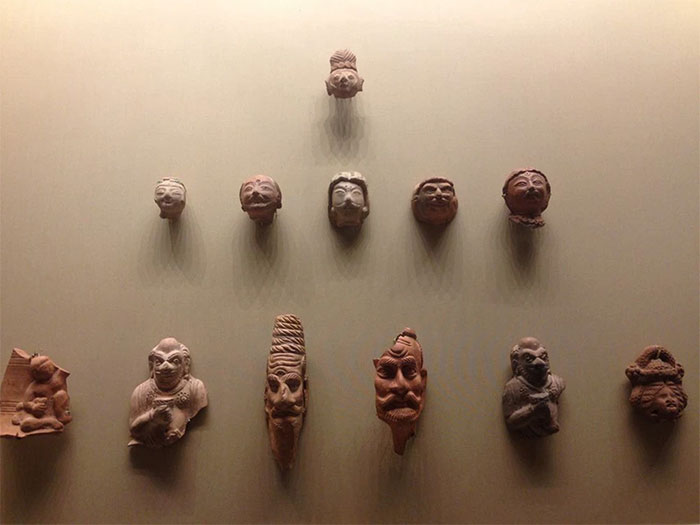

Small clay figurines found in Khotan from around the 2nd to the 4th centuries. (Photo: Wiki).

A “Forgotten” Kingdom

Various versions of the mythical story of the birth of Khotan share common themes with another mountainous region, Kathmandu Valley, which is also believed to have formed due to the draining of a lake.

Both lands are sites associated with seven successive Buddhas. A group of people from China and India are believed to be the original settlers in both newly formed valleys, and the first Indian settlers have connections to Indian kings.

In the stories of the kingdom of Khotan, the exiled son of Emperor Ashoka, Kunala, was also adopted by the Chinese emperor before becoming the founding ruler of Khotan.

Ruins of the Rawak Stupa outside Khotan, a Buddhist site dating from the late 3rd to the 5th centuries. (Photo: Wiki).

Despite the overlaps in mythical stories, the fates of the two regions are completely opposite. The Dharma has existed and thrived in the Kathmandu Valley, despite Nepal facing many issues.

But not in Khotan. In fact, history has largely forgotten the “precious gem” of a kingdom that was once so significant.

By the 12th century, the glorious Buddhist past of Khotan remained only a shadow. The power of China had gradually weakened. The imperial stature of Tibet had long collapsed. The Silk Road had diminished in its original importance. Waves of influence from the Turks and Iranians eventually brought a wave of Islam sweeping through the region.

The wooden painting discovered by Aurel Stein in Dandan Oilik depicts the legend of a princess who hid silkworm eggs in her headdress to smuggle them from China to the Kingdom of Khotan. Photo: Wiki.

The power of the Mongols was on the rise. Many scholars and historians in Tibet seemed unaware of the contributions of the Khotan kingdom to their culture centuries earlier.

The mythological story of the founding of Khotan is intertwined with how the Buddha created new opportunities in both time and space for the teachings to be spread, taught, and practiced. However, this is also part of the Buddhist literary journey that addresses the inevitable decline of the teachings.