Archaeological Evidence Suggests Fires Were Not Accidental.

Between 5500 and 2750 BCE, the regions now known as Romania, Moldova, and Ukraine were inhabited by a group known as the Cucuteni-Trypillia culture.

Although not as famous as the Sumerians in the neighboring Mesopotamia, the Cucuteni-Trypillia culture holds significant importance. They are recognized as the oldest known society in Europe and may be one of the crucial ancestors of human civilization as a whole.

Surrounded by the Carpathian Mountains and the Dnieper and Dniester rivers, the Cucuteni-Trypillia culture was incredibly advanced. They cultivated wheat, barley, and legumes. Additionally, they constructed large kilns for firing ceramics and wore jewelry made of copper. The axes used by the Cucuteni-Trypillia were also made of copper and were employed for chopping trees to build homes.

In fact, the term “impressive” is insufficient to evaluate the capabilities of this culture. Reinforcing wooden frames with dried clay, the Cucuteni-Trypillia were able to construct some of the largest buildings in the world – multi-story structures that measured the size of two basketball courts (nearly 700 square meters).

The buildings of the Cucuteni-Trypillia have puzzled archaeologists for centuries. The confusion arises not from the size of the structures, but from their remarkably preserved state – every 60 to 80 years, the residential complexes mysteriously burned down.

In fact, Cucuteni-Trypillia was not the only ancient community to record this phenomenon. Houses in Central and Eastern Europe were burned so frequently that scientists have given it a specific name: “Burned house horizon.”

Causes of the Fires

For a long time, the fires were thought to be caused by common reasons such as lightning strikes or enemy attacks. This was a reasonable hypothesis, especially since most prehistoric houses were filled with flammable materials like grains and textiles. Moreover, what reason would people have to intentionally destroy their own property?

However, scientists have proposed some surprisingly reasonable explanations for this phenomenon of self-immolating houses.

Mirjana Stevanovic, an archaeologist from Serbia, argues that the structure of the houses in this region “was destroyed by intentional burning, likely for symbolic reasons.”

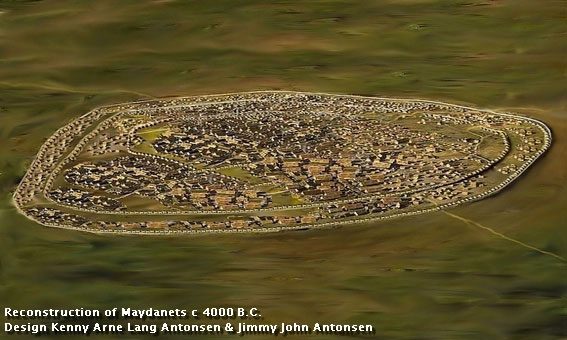

Reconstructed image of the Cucuteni-Trypillia community by researchers.

Her research echoes that of Vikentiy Khvoyka, another scholar who believed that the houses were burned when the inhabitants died.

Meanwhile, Evgeniy Yuryevich Krichevski, a Russian archaeologist, took a more practical approach. He posits that prehistoric peoples in Eastern Europe did not destroy the houses but rather reinforced them.

According to him, the heat of the fire would harden the clay walls, while the smoke helped repel insects. Several recent studies have also adopted a more pragmatic stance, arguing that old structures were primarily burned to make way for new ones.

Revisiting the Past

In 2022, a group of Hungarian archaeologists and conservators sought to gain a deeper understanding of this house-burning phenomenon by analyzing soil and plant materials recovered from a site near Budapest. The results indicated that among three burning events at this site, known as Százhalombatta-Földvár, two events appeared to have been initiated deliberately.

Archaeologists Arthur Bankoff and Frederik Winter took a different approach. In 1977, the duo purchased a dilapidated house from a farming family in the Morava Valley in Serbia. Coincidentally, this house was made from the same type of materials as the burned houses, so the archaeologists wanted to know what would happen if they set it on fire.

The results showed that while the wooden roof was destroyed, the clay-plastered walls of the house remained surprisingly intact. This, along with the fact that the experiment required a massive amount of fuel, suggests that prehistoric burnings were intentional rather than accidental.

Typical structure of a house built by the Cucuteni-Trypillia community

Bankoff and Winter were not the only researchers to conduct house-burning experiments in the name of science. In 2018, a group of Ukrainian and British archaeologists set fire to not just one, but two historically accurate structures.

However, this experiment differed in that instead of purchasing existing houses, they actively built the structures in the style of the Cucuteni-Trypillia culture. Ultimately, the results were almost identical. The walls of both buildings remained intact, as did many clay pots and small figurines inside. Furthermore, no fires spread, indicating that this activity was safe and controllable.

Once again, researchers were astonished by the amount of fuel that prehistoric peoples must have used to reach the maximum temperatures recorded in the sediments. Specifically, they would need an amount of wood equivalent to more than 130 trees for each single-story house and 250 trees for a two-story house. Consequently, a settlement of 100 houses would require a forest covering nearly 10 square kilometers to burn.